Biodiesel and the Ever-changing Political Landscape

October 16, 2017

BY Ron Kotrba

When the U.S. EPA issued its Notice of Data Availability on Sept. 26 seeking ways to reduce biomass-based diesel volumes in the 2018 and 2019 Renewable Fuel Standard—the former year’s volume of 2.1 billion gallons having already been finalized in 2016 by the Obama administration—it put the RIN markets in a tailspin and caused those in the biodiesel industry along with its political champions to ask, what is really going on? According to the NODA, issued just weeks after the comment period closed on the Trump administration’s disappointing first RFS volume proposal, the agency is seeking comment on possible ways to cut required biodiesel volumes in RFS based on supply concerns resulting from the lack of the $1-per-gallon tax credit and a projected reduction in biodiesel imports from Argentina and Indonesia resulting from the ongoing trade cases.

The problem with EPA’s logic is that as of 2010, the biodiesel tax credit has expired five times, but this ultimately did not stop the industry from growing and supplying product. The U.S. produced just slightly more than 300 million gallons in 2010, and nearly 2 billion gallons last year. Given the right policy signals, U.S. producers stand ready to ramp up production from existing assets and, as seen in 2016, invest in expansions, retrofits and new builds. Even with nearly 2 billion gallons of domestic production in 2016, various accounts indicate that one-third of existing domestic productive capacity remained idle. “We need to make sure we are adequately explaining to EPA the difference between domestic production and domestic capacity,” says Donnell Rehagen, CEO of the National Biodiesel Board. “We have plenty of capacity to fill demand in the market, and more.”

Furthermore, in the ongoing trade cases, only one preliminary determination was issued before the NODA came out. In August, the U.S. Department of Commerce issued preliminary countervailing duties in the antisubsidy case. In October, the commerce department will issue its preliminary antidumping determination, and then final antisubsidy and antidumping determinations will proceed late this year into next. “Our expectation in July was the tariffs would be delayed until November,” says Juan Sacoto, senior vice president of Agribusiness Consulting. “By coming this early, in August, there is not much adjustment time. Maybe EPA is acting too quickly. Or, maybe the agency would rather err on the side of caution.”

Michael Devine, the New England sales and marketing consultant for biodiesel distributor Amerigreen Energy, says, “The EPA administrator put this out for a reason.” What that reason is, however, as surmised by some biodiesel advocates, is appeasement of Big Oil, which has long sought to abolish the RFS by any means necessary. One of biodiesel’s biggest political champions, U.S. Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, called the NODA an outrageous bait-and-switch on a Senate floor speech the day it was issued. “This all gives me a strong suspicion that Big Oil and refineries are prevailing, despite assurances to the contrary,” Grassley said. “This seems like a bait-and-switch from the EPA’s prior proposal and from assurances from the president himself and cabinet secretaries in my office prior to confirmation for their strong support of renewable fuels.”

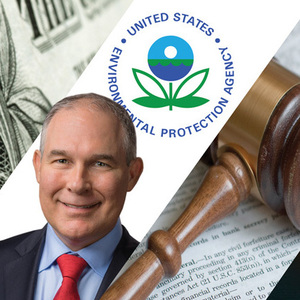

In the NODA, EPA repeatedly cites comments from oil lobby groups American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers and the American Petroleum Institute, legitimizing concerns that the Trump administration and an EPA led by Scott Pruitt back the oil industry in its quest to dismantle the RFS, despite campaign promises to uphold and defend the standard. “This NODA is another attempt by AFPM and others to kill a program they do not support,” says Doug Whitehead, chief operating officer at NBB. The gravitas the oil industry’s comments carry with EPA is evident, while it is equally evident that the agency discounts submitted comments and historical evidence from the U.S. biodiesel industry demonstrating it has outperformed every RFS increase to date, creates American manufacturing jobs, provides increased energy security and independence, adds much-needed value to rural economies, and is beneficial to the environment.

“That’s what’s most frustrating,” Rehagen says. “It appears as if EPA has not bothered looking at the facts that we’ve collected, and the studies, which support higher volumes in this specific RFS. We laid it out in May. It seems they have not read the whole thing, and it appears EPA is worried more about conjecture—the expired tax credit and reduced imports—despite the facts we presented. It’s so disappointing to me. We’ve answered these questions positively. The same thing on the tax credit, it’s not the first year the industry has been without it, nor is it the first year the industry has faced uncertainty.”

“There are major concerns about the ultimate legality of this,” Devine says, “and how it will be viewed if implemented. The market obviously reacted very bearishly once it was issued.” Devine notes that RIN markets recovered somewhat in subsequent trading sessions.

The NODA has essentially brought together all the policy issues facing the biodiesel industry today: The need to grow RFS volumes in this hard political culture, a recent court ruling that supposedly narrowed EPA’s discretion on its use of the general waiver authority, the tax credit and trade. Here we will examine each of these in the context of the NODA.

Court Ruling

In Americans for Clean Energy v. EPA, the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia issued its much-anticipated ruling in late July. In its NODA, EPA stated that the court ruled “that EPA improperly focused on supply of renewable fuel to consumers, and that the statute instead requires a ‘supply-side’ assessment of the volumes of renewable fuel that can be supplied to refiners, importers and blenders.” In response to the proposed 2018 standards, EPA stated in the NODA it received comments suggesting that the agency should interpret the undefined term “domestic” in “inadequate domestic supply” to account for only volumes of renewable fuel that are produced domestically. It is important to note that EPA footnoted this by stating the comments were from API, AFPM and Valero. The NODA goes on to cite numerous oil lobby comments on suggested interpretations of the word “domestic.” The agency is soliciting comments on whether certain definitions, offered by the oil lobby, would fit within the court’s ruling.

“EPA prevailed in the ruling except on the question of its use of its general waiver authority—the extent to which EPA is allowed to consider the demand side of the market when exercising its authority on the basis of inadequate domestic supply,” says Bryan Killian, partner with the law firm Morgan, Lewis & Bockius. “The court rejected that the lack of demand contributes to inadequate domestic supply, embracing that supply and demand aren’t the same thing—economics 101.” Killian says the key takeaway from the court ruling is that demand-side considerations cannot inform EPA’s decision in using the inadequate domestic supply prong of its general waiver authority.

Doug Hastings, an associate at Morgan, Lewis & Bockius, says the victory of the case is that it limits the tools EPA can use to reduce volumes. “The general waiver authority authorizes EPA to waive volumes only when there is an inadequate domestic supply of renewable fuels or a severe economic or environmental harm,” Hastings says. “In the future, if EPA wants to waive a volume under the inadequate domestic supply prong of its general waiver authority, it has more circumscribed discretion because it cannot consider demand-side constraints.” Hastings says this is seen “a little” in the proposed rule for 2018. “EPA did not initially propose to exercise its general waiver authority,” he says. “But it is now seeking comment through its supplemental NODA on whether there are any other ways to use its general waiver authority that are not foreclosed by the D.C. Circuit’s opinion.”

Rehagen says, “The court found errors in EPA’s rationale and the way it implemented its volumes, so yes, that is a victory, but if it does not lead to better understanding of how to make the RFS work as intended, then there’s not a lot of value to that victory.”

The D.C. Circuit Court formally issued its mandate in the 2014-’16 challenge on Sept. 22. This means the case is returning to EPA to figure out what to do now on the volumes for those years. There’s still a chance the EPA will seek Supreme Court review, but if not, then there will be a new rulemaking in the agency soon on what to do about the D.C. Circuit Court’s decision.

Congress’ intent with the RFS was to grow the advanced biofuels pool. “And the way these are nested,” Rehagen says, “you can’t look at growing that without growing the biomass-based diesel pool. With as much as EPA is struggling with setting volumes today, we also see them struggling on how to fix and provide a remedy for what was not done correctly a number of years ago.”

Trade

The NBB Fair Trade Coalition filed antidumping and antisubsidy petitions against Argentina and Indonesia this spring “to address a flood of subsidized and dumped imports … resulting in market share losses and depressed prices for domestic producers,” NBB states. “Biodiesel imports from Argentina and Indonesia surged by 464 percent from 2014 to 2016, taking 18.3 percentage points of market share from U.S. manufacturers. Imports of biodiesel from Argentina again jumped 144.5 percent following the filing of the petitions. These surging, low-priced imports prevented producers from earning adequate returns on their substantial investments and caused U.S. producers to pull back on further investments to serve a growing market.”

On May 5, the U.S. International Trade Commission made “unanimous affirmative determinations” in its preliminary phase antidumping and countervailing duty investigations concerning biodiesel from Argentina and Indonesia, a first step needed for the commerce department to proceed with its investigation. In May, the USITC stated there “is a reasonable indication that a U.S. industry is materially injured by reason of imports of biodiesel from Argentina and Indonesia that are allegedly subsidized and sold in the United States at less than fair value.”

In August, the commerce department issued preliminary countervailing duties in the antisubsidy case. As a result, importers of Argentine and Indonesian biodiesel are required to pay cash deposits on biodiesel imported from those countries ranging from 50.29 to 64.17 percent for biodiesel from Argentina, and 41.06 to 68.28 percent for biodiesel from Indonesia, depending on the foreign producer/exporter involved. Based on commerce department’s finding of “critical circumstances,” the rates for Argentina applied retroactively 90 days from the date of the Federal Register notice.

Myles Getlan, a partner at the law firm Cassidy Levy Kent LLP, says the commerce department is scheduled to issue its preliminary determination on dumping in October. “The antidumping and antisubsidy cases are two separate remedies intended to remedy two types of unfair trade practices,” he says. “It’s not uncommon to have companion cases when a petition is filed.”

Getlan says while it’s too early to speak to any dumping results, on the subsidy side, what those rates reflect are massive subsidies those governments provide to biodiesel producers. “In Argentina, the export tax regime has been the focus of attention by the U.S. and other countries for decades,” he says. “The effect of that is to severely depress soybean costs—the sole feedstock for biodiesel producers there—essentially to half of world market prices. That’s what you see in those countervailing duty rates.”

Indonesia has a similar export tax regime as related to crude palm oil. “But in Indonesia, they also have a biodiesel subsidy fund—it’s called that—and it is granted hundreds of millions of dollars,” Getlan says, adding that these are straight-forward, direct grants.

“When biodiesel producers in Argentina and Indonesia benefit from massive subsidies, it is no surprise they are in a position to flood the U.S. market with biodiesel,” Getlan says. “They have captured nearly 20 percentage points of market share from U.S. producers.”

The tax schemes used by Argentina and Indonesia are often referred to as differential export taxes, but Getlan says under U.S. subsidy law, it’s not necessary to consider the differential between soy and downstream products. “The way the program is analyzed, correctly, is that the government of Argentina sets the export tax at such a high level that it has a restraining impact on exports and trade flows, and therefore it causes distortions and distress on the price of soybeans, which has market-distorting effects.”

Any appeals to the rulings would not be considered until final determinations are made. Assuming final determinations and publication of orders, foreign governments and foreign and U.S. companies can appeal to the U.S. Court of International Trade, a federal court in New York, and argue whether the commerce department’s decisions are consistent with antidumping and antisubsidy statutes. If a party wants to appeal the decision of the U.S. Court of International Trade, then they can go to the federal circuit court of appeals in Washington, D.C. “Separately, foreign governments could challenge the results at the World Trade Organization,” Getlan says. “It’s purely a government-to-government process, which doesn’t directly affect U.S. determinations. But it’s an opportunity to challenge not whether the decisions are consistent with U.S. law, but with WTO agreements. It’s way too early to know whether Argentina or Indonesia will challenge the findings with the WTO. So far, we are confident what commerce found is entirely consistent with international law.”

Argentina challenged European antidumping tariffs at WTO and won. A WTO appellate body determined the duties were too high, and forced the EU to conform to its decision. The EU voted to significantly lower its duties. Now, as a result, shiploads of Argentine biodiesel are flowing into EU ports once again, causing some biodiesel producers in Europe, such as France’s Saipol, to cut production. While the WTO has yet to rule on Indonesia’s appeal, the EU biodiesel industry is preparing an antisubsidy case against Argentina and Indonesia.

“There is always the desire to look and compare the two, but they are very different cases,” Rehagen says, referring to the U.S. and EU trade cases. “I would caution everyone to not read a lot into what’s going on in the EU and impose that into this case. They have different merits.”

Pete Moss, president of Frazier, Barnes & Associates, says the EPA’s NODA employs flawed logic. “There is no evidence imports will stop as a result of the trade cases,” he says. “Just because we put tariffs in place—and we don’t even know if these are final—this doesn’t mean imports can’t or won’t come in from other areas.” Devine says people tend to confuse Argentine and Indonesian imports with all imports. “We’ll likely see a recalibration of the distribution chain,” Devine says. “In the EU, we may see a tolling of assets to bring more biodiesel into the U.S.’s East Coast from Europe.”

Moss adds that the NODA is baseless and unacceptable. “On the grounds of inadequate domestic supply, EPA can’t make cuts based on something there’s no proof of, based on the assumption that imports will stop and the tax credit won’t come back,” he says.

Tax Credit

In the context of what’s going on in Washington, D.C., the biodiesel tax credit is a complicated narrative, says Tim Urban, a member of the Washington Council Ernst & Young and leader of the firm’s Renewable Energy and Climate Change practice.

Three likely vehicles to pass a biodiesel tax credit this session or early next are comprehensive tax reform, a tax extenders package, or a disaster relief bill. “In the past month, the atmosphere has become rife with momentum for tax reform,” Urban says. “There is a decent chance a major tax reform bill will be enacted, either this year or early next.”

Donna Steele Flynn, also with WCEY, says there is a place for the biodiesel tax credit in a tax reform bill. “The blueprint acknowledges a transition from the current to a new tax system,” she says, “which would recognize certain provisions that exist in the code would get an extension, or get phased down over time.”

In early October, the House of Representatives and Senate took preliminary steps toward enacting comprehensive tax reform by pushing their respective budget resolutions forward. The House, on Oct. 5, considered the FY18 Budget Resolution, H. Con. Res. 71, which includes reconciliation instructions. Congressional leaders decided a budget resolution must pass to allow for the possibility of tax reform.

“This all takes time,” Flynn says. “They will not even start marking up the bill in the ways and means committee until the end of October. With all the other things stacked up that have to be done by the end of the year, there may not be enough legislative days for them to finish this session, so it may go into the first quarter of next year. But there is tremendous pressure to finish this and get a bill to the president’s desk. The survival of some members of Congress depends on it.”

In lieu of tax reform, a second possibility for extending the biodiesel tax credit is some kind of catch-all bill that would include must-do action items, making it more difficult to put off. “Those maneuver in a way that an extenders package could be inserted and signed into law,” Urban says. “That’s a second possibility if tax reform doesn’t go through this year. But as tax reform moves, there is less interest on the Hill to talk about anything other than reform because there would be no need for a stop-gap measure. The odds of the two are interrelated.” Flynn says disaster relief is another tax vehicle by which a biodiesel tax credit could be taken up. “Whenever a tax vehicle moves, interested parties try to get provisions into it,” she says.

In an exclusive interview with Biodiesel Magazine, Sen. Grassley says inserting a biodiesel tax credit into a disaster relief package will not be possible until every other opportunity fails. “We haven’t had tax reform in more than 30 years,” he says. “I’ve seen more movement on tax reform and simplification in the past few months than I have since 1986.”

Grassley says given the way Congress works, the tax credit won’t even be talked about until the midnight hour of putting together a bill before laying down the chairman’s marks. “A lot of things come together at the midnight hour, and this will be one of them,” he says. The senator notes his, NBB’s and domestic producers’ desire to change the incentive from a blenders credit to a domestic producers credit. “We hope to do that at the same time,” he says. “This was done in the Senate two years ago, but they didn’t do the same thing in the House, so we will make that attempt again. We hope to deal with the issue of not subsidizing imported biodiesel from Argentina. It’s stupid to have U.S. taxpayers pay a dollar a gallon importing biodiesel from Argentina. It’s a waste of $750 million.”

Grassley says he believes the biodiesel tax credit will ultimately be reinstated retroactively, “because it always has been,” he says. “Wherever you are, let your Congressmen and Senators know about it. You can’t take anything for granted today.”

Urban explains that the tax code struggles to put a value on certain benefits, for certain industry sectors. “Biodiesel provides public benefits for everyone walking down the street in terms of less pollution,” he says. “The whole idea of an incentive like this is to capture and identify public benefits to people who are producing what is being incentivized. If you look at the state of biodiesel before the tax credit was passed in 2004, it was an obscure niche. The federal government putting a price tag on the public benefits really put biodiesel on the map.” While some, such as the oil lobby and market purists, as Grassley says, oppose the biodiesel tax credit, Urban says it is essentially very new. “The credit is in its infancy and necessary,” he says.

Other Issues

The RFS reset process, point of obligation issue, and agriculture policy are all additional important issues facing the biodiesel industry.

“If EPA waives volumes by at least 20 percent in two consecutive years, it can trigger a reset,” Killian says. “Here, the reset provision would potentially be triggered by the waiver of volumes for 2017 and 2018. EPA could wait to see what happens with the 2017 litigation, but EPA could also presumably start the reset process soon.”

On the point of obligation issue, some obligated parties like Valero petitioned EPA to change this, asking the agency to take responsibility off refiners and move it downstream. “EPA had proposed to deny that petition, but it has not yet issued a final denial,” Killian says. “The point of obligation issue is dead in the same way that vampires are dead. The only thing that would surprise me is if no one challenges it when EPA formally denies it.”

Ag and RFS policies are inextricably intertwined. The farm bill will be up for consideration next year, as it expires in 2018, and committees have begun work on that. “When you look at ag programs in the farm bill, you can’t look at that without looking at renewable fuels,” Rehagen says. “There are supports built into the farm bill that also see supports in the RFS and higher volumes of renewable fuel. It’ll be interesting moving forward with the RFS and how it impacts higher volumes, as this will send a clear signal about the value this administration puts on what farmers do. As a farm bill has provided less support to farm economics, it becomes more and more reliant on support included through renewable fuels—biodiesel, ethanol and renewable diesel. If EPA looks at reducing out-year demand for renewable fuels, they would be harming farmers and the economics they work in.”

Henri Bardon, CEO of Solfuels USA, a 40 MMgy biodiesel plant in Helena, Arkansas, says people underestimate the fact that RFS is not just about emissions reductions, energy security and independence, but it’s also a farm support program. “It has significantly reduced government farm subsidies,” he says. He adds that the oil and gas industry, which is clearly behind the NODA, should embrace rather than seek to reduce biofuels worldwide, since biofuels can help shelter petroleum from an emissions crusade in the context of growing international interest in eliminating internal combustion engines.

When asked if federal policy in general is moving in the right direction, Whitehead says, “With this ever-changing landscape we live in, I wish I had a definitive answer. When you look at how Trump campaigned, and how the cabinet nominees testified in their confirmation hearings, this industry would have a sense of optimism. But in this hard political culture, we have to turn up the volume. We can’t hope for them to understand our story—rather we have to tell it to the people who can make a difference for us. We remain optimistic that the promises made in the past by this administration will be kept.”

The NODA appears to offer a self-fulfilling prophecy. EPA’s unwarranted fear of supply may ultimately cause the agency to reduce demand via reducing the RFS volumes, thereby ensuring supply constrictions. Rather than preemptively presupposing supply issues based on an unfinished trade case and the lack of a tax credit, perhaps EPA should let the market determine how supply will be secured. If, next year, or the year after, the biodiesel industry misses its mark, then certainly the government has the prerogative to consider adjusting the mandate—and demand as generated by RFS—down. But to shackle an industry based on presuppositions when the facts clearly show U.S. biodiesel producers have come back from the brink of extinction time and time again to break production and supply records mere months later is a discount of the highest, most egregious degree.

“What is frustrating for me is that it seems that there is not a clear line of information and fact-finding in EPA,” Rehagen says. “Our job now is to find out how we can do a better job getting information to the people who are expressing these concerns. The AFPM and others are definitely at play here. The question is, is anybody paying attention?”

Author: Ron Kotrba

Editor, Biodiesel Magazine

218-745-8347

rkotrba@bbiinternational.com

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Related Stories

The U.S EPA on July 17 released data showing more than 1.9 billion RINs were generated under the RFS during June, down 11% when compared to the same month of last year. Total RIN generation for the first half of 2025 reached 11.17 billion.

The U.S. EPA on July 17 published updated small refinery exemption (SRE) data, reporting that six new SRE petitions have been filed under the RFS during the past month. A total of 195 SRE petitions are now pending.

The USDA has announced it will delay opening the first quarterly grant application window for FY 2026 REAP funding. The agency cited both an application backlog and the need to disincentivize solar projects as reasons for the delay.

CoBank’s latest quarterly research report, released July 10, highlights current uncertainty around the implementation of three biofuel policies, RFS RVOs, small refinery exemptions (SREs) and the 45Z clean fuels production tax credit.

The U.S. EPA on July 8 hosted virtual public hearing to gather input on the agency’s recently released proposed rule to set 2026 and 2027 RFS RVOs. Members of the biofuel industry were among those to offer testimony during the event.

Upcoming Events