Field pennycress shows feedstock potential

October 25, 2010

BY Erin Voegele

Posted Nov. 10, 2010

Research conducted by the UDSA's Agricultural Research Service has identified a promising new feedstock for biodiesel production, Thlaspi arvense. More commonly known as field pennycress, the plant is a member of Brassicaceae family, which includes canola and camelina.

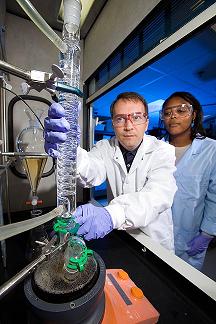

The project is being completed at the Peoria-Ill.-based ARS National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research. According Bryan Moser, an ARS research chemist, the research team has been studying field pennycress for approximately seven years, while the biodiesel component of the project has been ongoing for the past four years.

"The work that we do in our unit, the Bio-Oils Research Unit, spans basically everything from agronomic development and oil process, all the way to the production of biodiesel and evaluation of the properties of methyl esters that result from field pennycress oil," Moser said.

The work completed by Moser and other members of the field pennycress research team have shown that field pennycress seeds contain roughly 26 percent oil by weight. "On a yield-per-acre basis, you could expect to obtain somewhere around 100 gallons [of oil] per acre of field pennycress," Moser said. The plant is best suited for growth in the northern region of the United States.

One of the primary benefits of field pennycress is that it can be grown on existing soybean fields during the winter. This is because it's a winter annual, Moser said. In this application, the crop could be planted in the fall after the soybean harvest takes place. "After your soybean harvest, you would plant field pennycress on the same field," Moser continued. "You wouldn't have to apply any water, fertilizer or pesticides. The field pennycress overwinters on the farm field, which is actually also a [benefit] because it reduces or prevents erosion of the topsoil." In the spring the seeds can be harvested with existing farm equipment prior to soybean planting. "The planting of field pennycress doesn't affect soybean yield, which is a good thing," Moser said. "It also doesn't compete with food production, because the same farm field would be fallow over the winter anyway. You basically get a free oilseed crop by planting field pennycress in the fall and harvesting in the spring."

Part of the research conducted ARS research team involved the evaluation of biodiesel produced from field pennycress oil. The team produced a small lab-scale batch of the fuel, approximately one gallon, and evaluated it under applicable ASTM specifications. Findings have shown that field pennycress methyl ester characteristics, such as acid value, oxidative stability, cetane number, cold flow properties, viscosity, sulfur content, and phosphorous content, are all satisfactory under ASTM D6751.

The results of cold flow property testing were particularly notable. "We found a cloud point for field pennycress methyl esters at minus 10 degrees Celsius…and the cold filter plugging point…at minus 17 degrees Celsius," Moser said. "It definitely has better low temperature properties than soybean-based biodiesel."

According to Moser, future work will include trying to shorten the growing season for the crop. "At the moment, the harvest date for field pennycress is a little too late in the spring to allow for corn rotation," he said, noting that a shorted growing season would allow farmers to rotate the crop with both soybean and corn cultivation. "It would also be nice to improve the oil content of the seeds," he continued. "Although 36 percent is still good, it would be nice if it were even better…We'd also like to so some vehicle testing with actual engines to measure emissions."

Additional members of the research team included chemists Gerhard Knothe and Terry Isbell and plant physiologist Steven Vaughn. Results of the team's study were published in Energy & Fuels.

Research conducted by the UDSA's Agricultural Research Service has identified a promising new feedstock for biodiesel production, Thlaspi arvense. More commonly known as field pennycress, the plant is a member of Brassicaceae family, which includes canola and camelina.

The project is being completed at the Peoria-Ill.-based ARS National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research. According Bryan Moser, an ARS research chemist, the research team has been studying field pennycress for approximately seven years, while the biodiesel component of the project has been ongoing for the past four years.

"The work that we do in our unit, the Bio-Oils Research Unit, spans basically everything from agronomic development and oil process, all the way to the production of biodiesel and evaluation of the properties of methyl esters that result from field pennycress oil," Moser said.

The work completed by Moser and other members of the field pennycress research team have shown that field pennycress seeds contain roughly 26 percent oil by weight. "On a yield-per-acre basis, you could expect to obtain somewhere around 100 gallons [of oil] per acre of field pennycress," Moser said. The plant is best suited for growth in the northern region of the United States.

One of the primary benefits of field pennycress is that it can be grown on existing soybean fields during the winter. This is because it's a winter annual, Moser said. In this application, the crop could be planted in the fall after the soybean harvest takes place. "After your soybean harvest, you would plant field pennycress on the same field," Moser continued. "You wouldn't have to apply any water, fertilizer or pesticides. The field pennycress overwinters on the farm field, which is actually also a [benefit] because it reduces or prevents erosion of the topsoil." In the spring the seeds can be harvested with existing farm equipment prior to soybean planting. "The planting of field pennycress doesn't affect soybean yield, which is a good thing," Moser said. "It also doesn't compete with food production, because the same farm field would be fallow over the winter anyway. You basically get a free oilseed crop by planting field pennycress in the fall and harvesting in the spring."

Part of the research conducted ARS research team involved the evaluation of biodiesel produced from field pennycress oil. The team produced a small lab-scale batch of the fuel, approximately one gallon, and evaluated it under applicable ASTM specifications. Findings have shown that field pennycress methyl ester characteristics, such as acid value, oxidative stability, cetane number, cold flow properties, viscosity, sulfur content, and phosphorous content, are all satisfactory under ASTM D6751.

The results of cold flow property testing were particularly notable. "We found a cloud point for field pennycress methyl esters at minus 10 degrees Celsius…and the cold filter plugging point…at minus 17 degrees Celsius," Moser said. "It definitely has better low temperature properties than soybean-based biodiesel."

According to Moser, future work will include trying to shorten the growing season for the crop. "At the moment, the harvest date for field pennycress is a little too late in the spring to allow for corn rotation," he said, noting that a shorted growing season would allow farmers to rotate the crop with both soybean and corn cultivation. "It would also be nice to improve the oil content of the seeds," he continued. "Although 36 percent is still good, it would be nice if it were even better…We'd also like to so some vehicle testing with actual engines to measure emissions."

Additional members of the research team included chemists Gerhard Knothe and Terry Isbell and plant physiologist Steven Vaughn. Results of the team's study were published in Energy & Fuels.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Upcoming Events