Clearing the Way for Byproduct Quality

October 25, 2011

BY Bryan Sims

A high degree of importance is placed on the quality of methyl esters, properly so, particularly when used as on-road fuel. So much so that for biodiesel to be a legally registered fuel additive with the U.S. EPA, it must meet strict industry specifications as prescribed by ASTM D6751 prior to blending with diesel in order to ensure proper, consistent performance. Additionally, the National Biodiesel Board has implemented its own quality assurance program, BQ-9000. Further biodiesel quality specifications in different applications under ASTM requirements include D975-08a for diesel fuels in on- and off-road applications, D396-08b for fuel oils such as home heating oil and boiler applications, and D7467-08 for diesel fuel oil with biodiesel blends ranging from 6 to 20 percent.

With all the stringent quality measures imposed on producers, there is, however, no governing body that imposes or oversees similar quality standards for crude glycerin, the byproduct that’s left at the end of the transesterification process. Most biodiesel production today involves homogeneous alkaline catalysts such as sodium methylate. The transesterification of triglycerides with methanol generates a biodiesel phase and a glycerin phase. Impurities such as catalyst, soap, methanol and water concentrate in the glycerin phase, which is typically neutralized with acid, and the cationic component of the catalyst is incorporated as a salt. Remaining contaminants such as methanol, soaps and water can render the composition of glycerin to consist anywhere between 40 and 80 percent pure glycerol, depending on the feedstocks and processes employed.

Because of the these differences in purity levels, crude glycerin is viewed as a highly variable commodity from plant to plant, making it difficult for a regulatory body or standards committee to impose any kind of uniform quality standard across the board, says Mark Rice, CEO of Northbrook, Ill.-based chemicals and fuels testing firm Biofuels Technology LLC.

“Quality of crude glycerin has to do with everything from the weather to the feedstock that they’re using, to the plant manager who’s on shift, so the glycerin byproduct is very inconsistent and, for the most part in the U.S., is very poor quality,” Rice explains. “It’s a hard product to manage. For some plants it’s all over the board in terms of what crude glycerin means or what that glycerin product looks like. They are primarily making sure that they can make the specification requirement for their ASTM biodiesel product, and what’s left over isn’t something that they have much control over, or the economics aren’t there for them to spend the money to refine that into some kind of a product to get an added value for.”

According to information based on a report authored by the U.S. census bureau, the NBB and brokerage house HBI International, Rice says an estimated 343,000 metric tons of glycerin is projected to enter the market by the end of this year. In 2010, 245,000 metric tons of glycerin was produced, compared to glycerin’s highest production volume ever at 376,000 metric tons in 2008.

Brent Pohlman, marketing director for Omaha, Neb.-based fuels and chemicals testing company Midwest Laboratories Inc., tells Biodiesel Magazine that while the firm isn’t seeing the volumes of crude glycerin samples like it once did during the industry’s boom year of 2008, quality remains a concern.

“It was typical where we would get anywhere from 20 to 30 samples per day,” Pohlman says. “We haven’t seen those kinds of volumes come back since, but we’re seeing that people are more concerned about quality right now.”

The Different Grades

Irrespective of the projected volumes of glycerin this year, it’s still an important ingredient and chemical building block for the production of high-volume industrial chemicals such as propylene glycol, epichlorohydrin, acrylic acid and polyhydroxybutyrate.

Advertisement

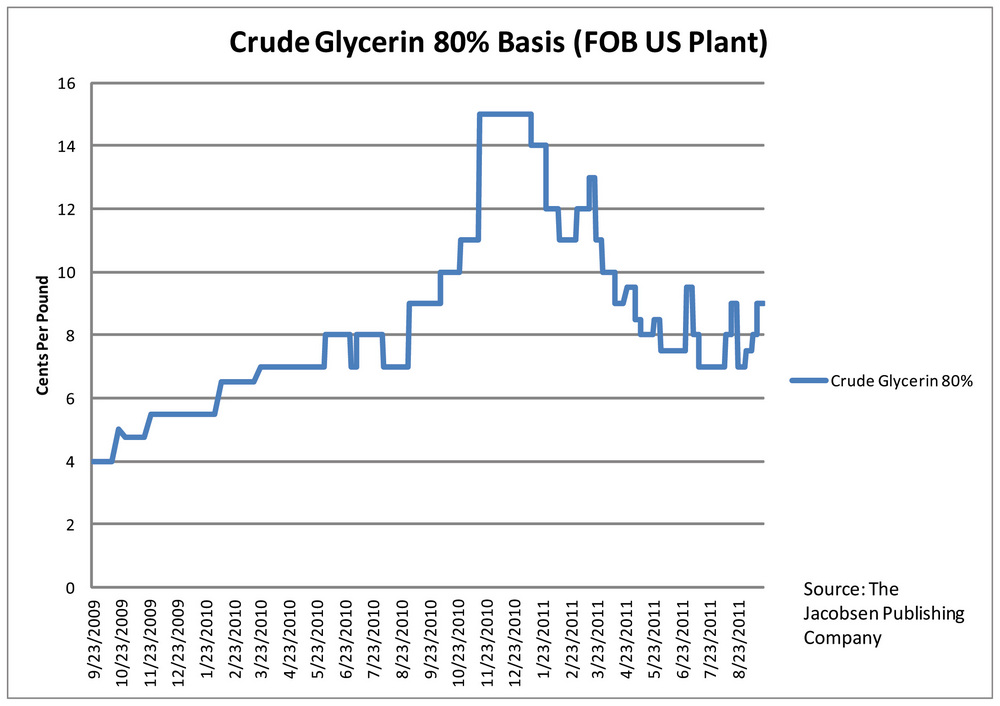

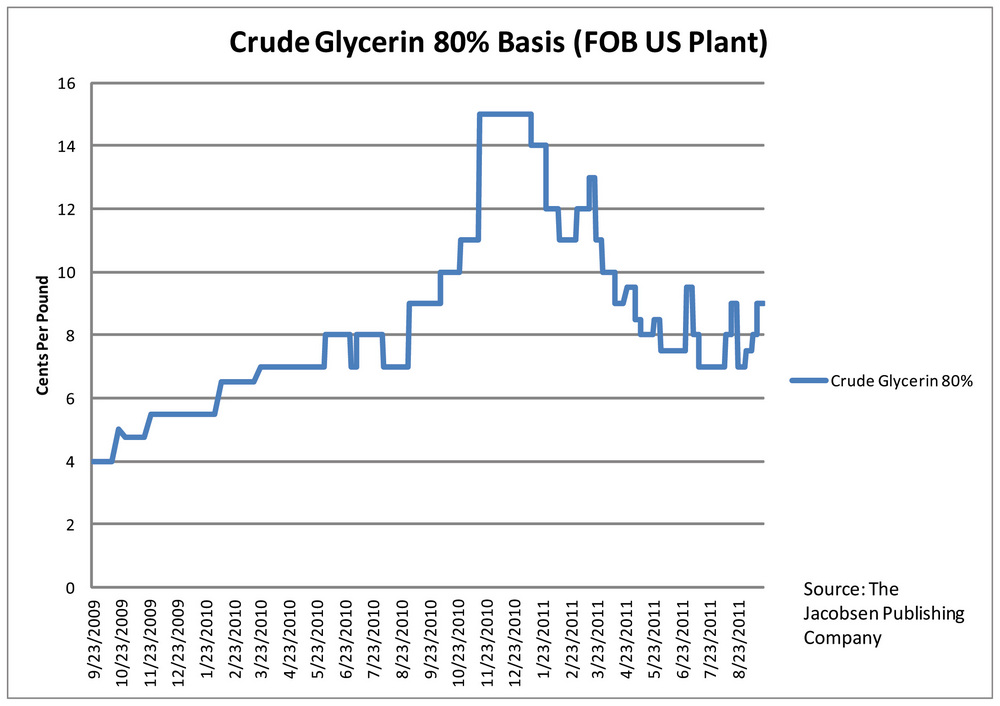

Biodiesel producers have the choice of refining their crude glycerin into two higher forms—technical or USP grade (U.S. Pharmacopeia)—to get an added value for their byproduct because, as a rule, the purer the glycerin, the higher the market value. The purity requirements for the emerging applications of glycerin vary, and are often intermediate to the crude and refined grades previously established for the classical applications. Biodiesel companies can either refine crude glycerin at their production facility by installing glycerin refining equipment or methanol recovery systems that can strip methanol out of crude glycerol. Producers can also ship their crude glycerin to companies such as Biofuels Technology LLC or Midwest Laboratories for testing and analysis. While some biodiesel producers refine their crude glycerin to technical grade, the majority of them can’t afford it and are left having to dispose of it according to regulatory requirements or sell it at a very low price—between 1 and 8 cents a pound in some cases. Because of its low value, crude glycerin is sometimes used as a dust suppressor on roads or burnt for energy even though its Btu value is low. Interest, however, in finding other applications for crude glycerin, such as a supplement for animal feed, is on the rise. At press time, crude glycerin was selling at 7 cents a pound, according to The Jacobsen, a fuel, feed and chemical commodity pricing and market analysis firm based in Chicago.

“Everyone in the industry has a different brand of crude glycerin,” Rice says. “Because of that, the price that most producers are getting is very low, and if they get a price that’s greater than what the market is, and it seems to be too good to be true, it usually is.”

Technical-grade glycerin usually has a water-white pigment to it and a purity of 97 to 98 percent with most of the contaminants completely removed. Technical grades of glycerin are usually classified by derivation of feedstocks such as tallow, which are considered lower grade, and vegetable oil-based (or kosher), which are considered higher grade. These two subforms of technical-grade glycerin are typically designated for polyols and alkyd resins markets. Technical or crude forms can also be further refined to 99.7 percent purity or higher to meet USP-grade glycerin, suitable for food, personal care, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals and other specialty applications. At press time, USP refined glycerin with 99.7 percent purity was selling at 43 cents a pound, according to The Jacobsen.

Unlike crude and technical grades of glycerin, the quality of USP glycerin is closely regulated by the Federal Drug Administration and Federal Communications Commission. This assures buyers of the glycerin’s quality that might not otherwise be achieved through physical and chemical testing alone. While it may be produced in similar processes, technical-grade glycerin doesn’t have to be in compliance with USP, FCC or FDA requirements and therefore typically conforms to specifications mutually agreed upon between the buyer and seller.

Quality End-Use Assurance

For large biodiesel producers such as Ames, Iowa-based Renewable Energy Group Inc., overseeing glycerin quality, particularly of technical-grade glycerin, is paramount to the overall economics of its operations, says Dave Elsenbast, vice president of supply chain management.

“REG has always looked at glycerin as a coproduct as opposed to a byproduct,” he says. “I think when we look at it that way, we look at marketing our glycerin to the higher value end-markets that we can target, as opposed to disposing of a byproduct at prices that just move the product. We’re always looking for ways to maximize our biodiesel crush margin, and therefore we take a very serious approach to marketing our glycerin.”

Advertisement

Currently, REG has six operating biodiesel plants with a combined installed production capacity of 212 MMgy. Elsenbast says five of those facilities produce a consistent quality of crude glycerin, while the other, a plant in Seneca, Ill., produces technical-grade glycerin. In total, REG produces about 190 million pounds of glycerin a year out of its operating plants.

While crude product may get discounted in the open market, making it difficult for producers to find useful markets for it, Elsenbast advises other producers to regularly test batches of their crude in-house or through third-party labs to maintain quality throughout continuous processing.

“We think of glycerin as a very competitive energy business, and we have to participate and do well every step in the business process,” Elsenbast says. “Certainly, being a consistent supplier of high-quality glycerin and selling that to the high-value market helps us succeed in the marketplace.”

Like REG, Keystone Biofuels LLC, a 24 MMgy multifeedstock plant in Lower Allen Township, Pa., places as much importance on its quality of glycerin as it does fuel. According to President Ben Wooten, his company recently upgraded the facility’s efficiency by installing a methanol recovery system, which has opened new markets for Keystone’s crude glycerin.

“Historically, most of our glycerin in 2010 went down the street to a concrete company that burned it for fuel,” Wooten says. “Now, we’re getting calls from engineering firms that are actually putting out their own quality specifications where some want a certain percentage of methanol, a certain percentage of glycerol and so forth. We figured if we do a couple steps like that, it opens different markets so we’re not relying on just one.”

By reinvesting in the plant for upgrades such as glycerin purification and methanol recovery systems, Wooten believes this strategy will determine who will ultimately remain profitable heading into next year.

“Those of us that are reinvesting in the plant to get those efficiencies are going to get a better leg up on the ones that aren’t doing that,” Wooten says. “I think you’ll see kind of an evolution, hopefully for those of us that are investing it pays off, and I think those that aren’t could still play in a niche market.”

Plants that have made upgrades like Keystone Biofuels, or those considering this strategy, may reap the benefits, but Rice suggests that the economics of adding equipment to handle glycerin might be negligible in today’s volatile economy. He adds that dealing with opportunistic glycerin traders who sometimes take it and behave irresponsibly is something producers should consider, because when crude glycerin is sold, “the customer trail ends with them,” he says.

“If biodiesel plants are selling to people that don’t know what they’re doing and don’t handle their glycerin in a safe and ethical manner, it could come back to bite them in a really bad way,” Rice adds. “Understanding the technicalities of glycerin, where it goes and knowing the composition of it is very important and often overlooked.”

Author: Bryan Sims

Associate Editor, Biodiesel Magazine

(701) 738-4974

bsims@bbiinternational.com

Upcoming Events