Advice to Operate By

PHOTO: BDI-BIOENERGY INTERNATIONAL AG

November 2, 2012

BY Ron Kotrba

For biodiesel refineries, a good maintenance plan starts with good training. Austria-based BDI-BioEnergy International AG, which has built more than 30 plants worldwide, starts its plant personnel training routine during construction of the facility. “Operator training is essential for stable, effective biodiesel production,” says Christine Riedl, senior engineer with BDI process engineering. Laboratory training is first, followed by classroom operator training during cold commissioning consisting of familiarity with feedstock parameters, chemicals used, safety regulations, reactions, production units, operation modus, safety material data sheets, the process control system (PCS) and troubleshooting. During this phase, operators are also involved in the cold commissioning and are familiarized with operating the equipment, valves, instruments, process control system and the entire installation. “BDI will also provide special training for pumps, instruments and process control system,” she says. Also the subsuppliers or vendors of special equipment such as centrifuges and steam boilers are on-site for equipment training. Besides technical documentation for equipment, troubleshooting and maintenance lists are available during commissioning. She says best results are achieved when operators are involved in commissioning and maintenance works as early as possible.

The third phase of training starts during hot commissioning, where operators should be responsible not only for biodiesel production but also equipment maintenance itself such as oil changes, pump sealings and new calibration of instruments. “One of BDI’s responsibilities is to also train operators in preventive maintenance,” Riedl says. “Listening to cavitation of pumps, or unusual noises in the plant, allowing the operator to react before the equipment will have greater damage, which can lead to a high production loss.” During the commissioning, BDI organizes an operator plant tour as to “get a feel” for the process equipment. “A walk around ensures that operators are able to react as soon as possible on unexpected interruptions or equipment failures,” she says.

While training operators is essential, Riedl says a plant maintenance director ultimately responsible for upkeep duties must develop a maintenance plan that includes operation hours, oil changes and the like; listing of necessary maintenance items that can be done during an unscheduled stop; planned, or scheduled maintenance stops (involving all necessary subsuppliers); spare parts logistics including statistics, most needed parts, delivery times and availability; and cleaning procedures including clean-in-place systems, intervals for cleaning and so forth.

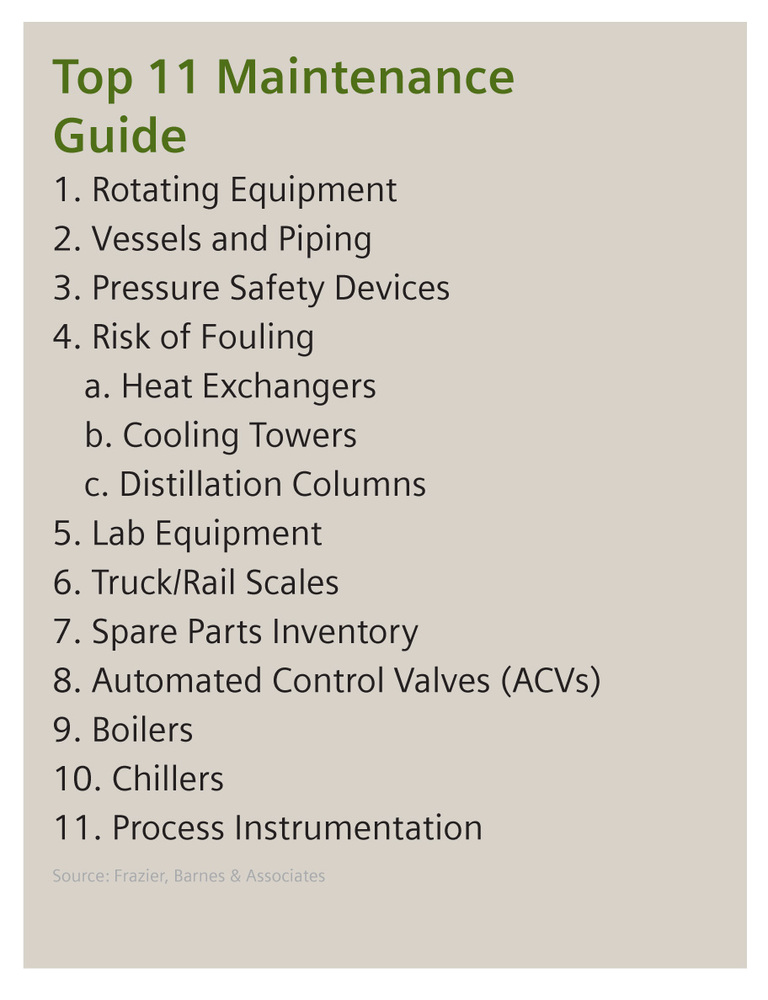

“Prevention is always better than reaction,” says Warren Barnes, vice president of Frazier, Barnes & Associates. “It creates havoc for an organization when you have unscheduled downtime versus planned downtime. Customers don’t like it. Feedstock suppliers don’t like it. And owners don’t like it. It implies that you’re not in control of your business.” The biodiesel supply chain has such a small amount of product in it that “process hiccups,” as Barnes says, “can literally run your customer out of product.” Therefore, Barnes says regularly scheduled maintenance, particularly on rotating pieces of equipment, is extremely important.

Planned downtime should be scheduled with some regularity, whether it’s one day a month and two to three days every quarter, or even a shift a month and a few shifts a quarter, Barnes says, with a well-thought-out list of things to be checked. “It’s unrealistic to expect any plant large or small to run for months without some scheduled maintenance,” he says. “We’re not talking two or three weeks of downtime—maybe a shift, maybe two shifts on a holiday, schedule it around what the demand for your product is.”

Riedl agrees. “The maintenance plan has to be in place and stops must be planned,” she says, adding that several maintenance items can be done during an unexpected or expected stop of the plant. Some producers only consider costs for spare parts and the maintenance team during unscheduled stoppages. “They don’t think about the time and the costs for an unexpected stop of production,” Riedl says. “There’s not only the time for the equipment repair, but also the time to stop and start the plant.”

Advertisement

Stocking spare parts must also not be overlooked. While holding inventory costs money, it’s usually less costly than a failure after which a part must be ordered and delivered. “Equipment vendors know parts have limited life,” Barnes says. “They will provide required spare parts for their equipment if asked, and most will without asking. To them it’s just a normal course of business, when they get a proposal, they automatically get spare parts. Regardless of plant size or sophistication, it is fundamental for every plant, for every piece of equipment, to have them in inventory.” Riedl says there are different equipment parts that can cause hang-ups and downtime. “First, there is all rotating equipment like pumps or centrifuges, causing long shutdowns if there is no preventive maintenance in place and no spare parts on stock,” she says. “Second, fouling of the equipment is always an issue—that appears not suddenly but lingering. Slowly the quality of the products decreases and the quantities are going down.” This can be avoided by using purified feedstock according to input specifications and by having an established maintenance plan. “Basically,” she says, “a bad organization of even the smallest parts can have an impact on the production in several parameters.”

There’s only 365 days in a year, so when developing a maintenance routine, back off from there with a number of days for scheduled maintenance. Then, Barnes says, “things will break,” so add a number of days in a routine for unscheduled maintenance. Once a routine is established, at least there is something to hold people accountable to and improve upon. “If you don’t establish one, you don’t have anything to measure against,” he says. “It’s all about capacity utilization. The best return is the one you get on that extra gallon you produced yesterday.”

As it relates to maintenance activities with flammable materials, Barnes says lockout/tag-out and confined space entry procedures are critical. “You can go into a vessel that has been purged with 100 percent nitrogen and the first three breaths seem normal, but then you will rapidly lose vision, fall down, lose consciousness, and you will die,” he says. “In maintenance, everyone wants to do it quickly because you’re not making money when the airplane’s not flying, and that’s when personnel safety is at the greatest risk.”

Often overlooked are items like pressure relief valves, which could go unneeded and unchecked for five or 10 years and, as Barnes says, people assume they’ll work. “But the way you find out it didn’t work is you blow a weld out and have a catastrophic failure of a vessel,” he says. Barnes advises plant owners to use insurance carriers to help identify areas of risk. “He is your helper, if you do what he says, you have an argument for lower insurance costs,” or, at least avoidance of insurance increases. Owners can assess the industry’s experience modifier and determine how their plant compares. “That’ll tell the management how they’re doing,” Barnes says.

Midlands Biofuels is a small, community-scaled producer in Winnsboro, N.C. Like many similar-sized plants, Midlands was built not by a large design/engineering firm, but by a few ingenious, resourceful individuals with a vision. Midlands co-founder “Bio” Joe Renwick speaks with Biodiesel Magazine about his maintenance experiences over the years. The first words of advice Renwick shares are, “Just because something says it is biodiesel-compliant does not mean it will withstand the biodiesel production environment.” Renwick and partner Brandon Spence built Midlands with whatever they had available as far as parts, valves and pumps go. They designed everything themselves, including its methanol recovery system. Renwick says Midlands uses hose instead of piping in many areas where piping was either too complicated or expensive, and where flexibility was desirable. “We replaced every single hose inside this facility, and in the tank farm,” he says. So-called “biodiesel-compliant” hoses were anything but, he says. Four years ago, Midlands switched out all hoses with Thermoid Vapor-loc hose. “It’s amazing,” he says. “We’re very pleased with it.” It’s made of multiple layers and eliminates permeation and other things that cause biodiesel hoses to fail. “It’s thick and heavy-duty, but still pliable,” he says. “It’s not only better, but cheaper. When we first started, we had Mustang hose, they said it was great but biodiesel would permeate and leak like no body’s business. Our Thermoid Vapor-loc hoses trap in all those gases that could permeate, so it’s good not only because it alleviates replacement costs, but it makes the work environment safer.”

Midlands uses Schedule 80 PVC instead of steel in a number of piping applications. “It turns out not all manufacturer’s Schedule 80 PVC can withstand biodiesel,” he says. We had a lot of pipe fail and then spent a lot of time reprocessing. It was a hell of a nightmare.” Renwick says Lasco-brand light gray fittings were the source of the pipe problems. “They all failed,” he says. “They swelled and deteriorated. At first we started seeing bits of gray pieces of gray shavings in the biodiesel that became soft and rubbery to where you can squeeze it, it was really weird. They were in the bottoms of our tanks and filters. We had tanks with that Lasco fitting at the bottom and it broke loose at the threads. Biodiesel just began leaking out on the floor, not a gush but a trickle. We quickly evacuated the tank and broke it all down. We had three tanks fail, and then we had to gut the entire system and replace all the PVC fittings and all piping. Specifically what was failing was the fittings, the pipe was holding up. It’s not all Schedule 80 PVC fittings either, it’s just this certain brand, and it’s a light-colored gray.” He says regular white Schedule 40 PVC fittings held up better than this brand of light-gray Schedule 80.

Other advice Renwick shares includes pipe threading techniques. “When threading pipe, don’t do to the standard one or two inches,” he says. “Do it a little bit bigger, it makes fitting tighter, it seals a hundred times better. Also, a lot of companies say they have pipe dope that works for biodiesel. We now use Slic-tite, it actually works. We’ve used a number of other brands and they leak.”

Advertisement

Renwick says Midlands uses Wilden diaphragm pumps. “They’ve been amazing,” he says.

Midlands designed its own methanol recovery system and after a series of trials and errors, mostly in cooling the vapors enough to condense, he said they found a $20,000 commercial chiller from government surplus and paid only $750. It uses a lot of electricity and requires a lot of space, but chills extremely well. Methanol recovery not only requires heating and cooling, but also vacuum pumping. “We tried a number of styles of vacuum pumps,” Renwick says, “and found the only safe and reliable option is a liquid ring vacuum pump.”

Why has Renwick shared this information Midlands learned along the way? “The way I feel about the biodiesel industry right now is, if we don’t become more of an open-source industry where we’re helping each other, we’re all going to be screwed,” he says. “The biodiesel industry is not a real pretty industry to be in right now, it’s pretty tough. If I can give information right now that will help someone else do it better and keeps this industry alive, I’m glad to do it.”

Author: Ron Kotrba

Editor, Biodiesel Magazine

218-745-8347

Upcoming Events