Pieces of the Puzzle

January 11, 2012

BY Holly Jessen

If there’s one thing the experts can agree on it’s that hedging is a complex topic. One simplified way to describe it is as a type of insurance. In a forward contract, an ethanol plant that has a contract for corn at a certain price will save money if, later on, the price of corn shoots up. On the other hand, the company takes the risk that the price of corn could also go down. “Somewhere you need to be able to offset the risk of that movement,” says Jim Leiting, general manager of Big River Resources LLC. “Because if the value of your corn changes, for every 30-cent move in corn, you need a 10-cent move in ethanol to stay even.”

One common hedging practice is for ethanol producers to also enter into a contract on the futures market, typically to sell corn at a specific price on a certain future date. An ethanol plant that has a forward contract with a farmer is obligated to purchase corn, say at $7 a bushel, even if corn prices fall to $6. To protect from a big financial loss, the company can enter into a futures contract at the same time, theoretically guaranteeing a certain price. By hedging one investment against another, the company reduces its potential loss. “The whole principle is to limit your exposure to flat price movement in a commodity market that’s very volatile,” Leiting says.

Ethanol plants typically seek price protection for four main commodities—corn, natural gas, ethanol and distillers grains. Some plants also produce corn oil. Distillers grains and corn oil cannot be hedged directly. Although distillers grains is traded on the futures market, there’s not enough volume for it to be an effective hedge, Leiting says. The products can, however, be hedged against the commodities they track in price movements, such as corn and soybean oil.

Today, managing the margins is vitally important, according to Leiting. In 2011, corn ranged from as low as $3.80 to more than $7. “Our operating margins, generally in the ethanol plant, are about 20 cents a gallon,” Leiting says, “so you really can’t have exposure to that flat price swing.”

Part of managing the margin is locking in the price of corn as well as ethanol. “They may be missing out on even bigger profits by doing that, because they are locking in these prices early,” April King, assurance and advisory services supervisor for Christianson & Associates PLLP, tells EPM. “But most of the plants have learned, I think, that they are happier doing that and that’s a safer route to go, rather than leaving themselves exposed to the fluctuations of the different commodities.”

Advertisement

The ability to make forward sales of ethanol hasn’t always been available to producers, points out Neal Kemmet, general manager of Ace Ethanol LLC, a 40 MMgy ethanol plant in Stanley, Wis. His company selected a Canadian firm, Elbow River Marketing, specifically because it allowed Ace to lock in ethanol prices. “That certainly wasn’t the case three years ago when we signed on with Elbow River—they were one of the three ethanol marketing firms that would, in fact, fix a price on a forward ethanol contract,” he says.

Surprisingly, there are still some ethanol plants that do almost no hedging. “I was just out at a plant last week that did almost no hedging,” King said. “However, because of their location, it is working for them—they are completely playing the spot.”

A company that operates in the spot market is a market taker. It takes whatever the market gives them, good or bad, says Jason Sagebiel, director of renewable fuels for INTL FCStone, “which can be very good—we’re coming off good margins right now [in December]—or it can be very bad—we are going into bad margins as you go into Q1,” he says. “Everything has its pros and cons.”

Some ethanol producers do both. At Ace Ethanol, a certain percentage of ethanol sales are left open to the spot market, Kemmet says. Those percentages change, depending on the time of year, taking into account that the first quarter is typically difficult from a spot market perspective, while the fourth quarter is good. “Our profit targets and the amount we are willing to hedge is a lot different from quarter four than it is from quarter one,” he says. “We treat each quarter differently when it comes to how much margin we are going to lock and what our margin targets are.”

Hedging History

To understand hedging strategies for the ethanol industry today, it is helpful to look back. Many of the founding members of the industry were farmers who hailed from cooperatives that dealt with buying and selling of only one type of product—corn and other grains. “The strategies for managing price volatility were pretty straight forward back in the old days,” King says, “so there was limited or simplistic hedging that took place.”

The industry has evolved significantly. “We are learning a lot, not only about production and efficiency, but the management is getting a lot savvier on developing hedge strategies,” she says.

Hedging strategies, of necessity, have also evolved as the market has. When Leiting began working in the ethanol industry in 2005, ethanol prices were correlated with unleaded gasoline prices, he says. Today, ethanol prices track more closely with corn prices. “As we rolled through 2006 and 2007, we saw a decoupling of ethanol and unleaded gasoline, or what became RBOB pricing, meaning they each had a supply and demand curve, and what we saw is you might see gasoline rise and ethanol may not have risen with it,” he says. “But what came along with that is the cost of ethanol, and the cost of ethanol production began to be recognized by the buyers, and ethanol prices began to correlate more with corn.”

Advertisement

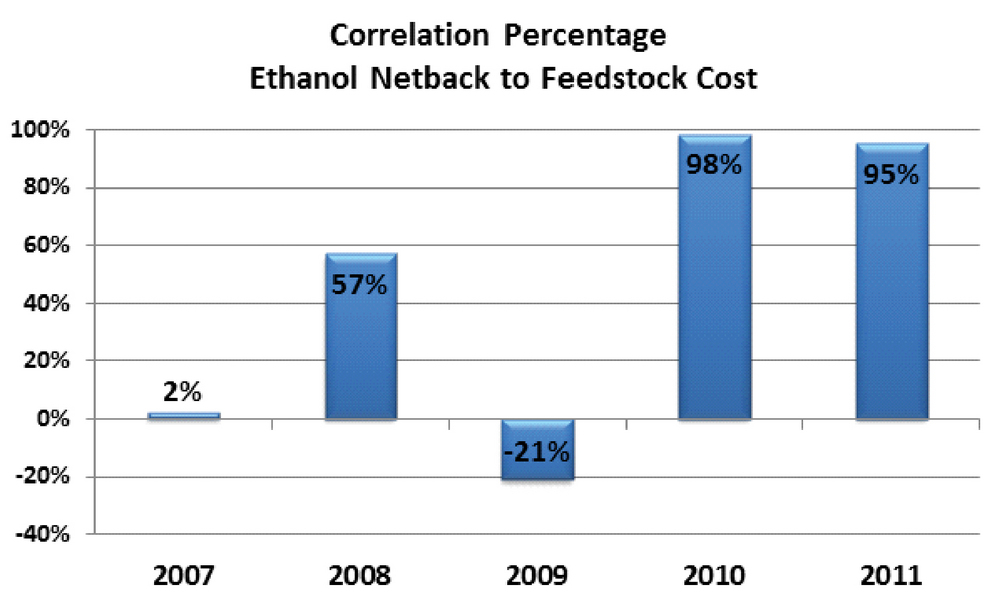

Data from Christianson & Associates’ Biofuels Benchmarking program, in which 63 ethanol plants participated in 2010, shows that the price relationship between corn and ethanol was negatively correlated in 2009, a correction year after the volatility of 2008. In 2010, however, corn and ethanol pricing was nearly perfectly correlated, meaning reduced volatility, lower risk and stabilized profits. That strong correlation between corn and ethanol prices continued in 2011, with benchmarking program data for the first three quarters showing an about 95 percent correlation.

Another change from 2005 to 2007 compared to today is narrower margins, Leiting says. Pre-2008 margins were wide enough that commodity price changes didn’t hit ethanol plants nearly as hard as they do today. “You may have had less or more, depending on what that market did, but with the margin being as wide as it was, you still had a profitable plant,” Leiting says. Today’s ethanol plants, however, are likely to be working with margins between 10 and 20 cents a gallon. “In that environment, your ability to be profitable is very sensitive to the volatility in these four key commodities,” he says.

A lesson from the past is the importance of availability of working capital. “In 2008, when the corn market went clear to $8, working capital became so constrained that even large companies such as ADM, Cargill and Bunge reached the limits of what they could borrow against their positions to maintain their hedge,” Leiting says. Of course, 2008 was the year of bankruptcies, including VeraSun Energy Corp., the second largest ethanol producer in the U.S. at the time. “If you have positions on, and the market moves in a direction against you in the futures market, then you have to be able to fund those moves and keep your hedges in place,” he says. “So working capital and the availability of working capital is a huge issue.”

Accounting Puzzle Piece

Something Christianson & Associates has discovered is that because there are different accounting options for derivative (or financial) instruments and hedging, it can be difficult to compare the hedging data of one ethanol plant to another. Specifically, ethanol plants have the option to recognize certain instruments or not, which can be confusing or misleading to board members or investors. This can be a significant issue the industry as a whole should be aware of, King says.

The issue starts with a 1998 statement from the Financial Accounting Standards Board, outlining different accounting options, the first two of which are known as fair value hedges and cash flow hedges. Due to the work involved, and the fact that these accounting methods are very complicated, the majority of, if not all, ethanol producers do not use these accounting methods. “Normally the benefits don’t outweigh the costs,” King says.

The third category, which King refers to as normal derivative accounting, requires that all derivative instruments are recorded on the balance sheet with any gains or losses in the fair value charged through earnings in the current period. When companies utilize forward contracts they have two options: recognize the forward contracts as derivative instruments or designate them as normal purchases and sales. With the second option, the end result is that these forward contracts become off-balance-sheet arrangements, for which the changes in fair value are not recognized in the financial statements. This simplified accounting method worked well for ethanol plants in the past, when an ethanol plant’s hedging efforts primarily included forward contracts, King says. “In effect, only half of the economic hedge is being recorded,” she says. “In annual financial statements, the effect is not as obvious since hedging gains and losses are combined with the related revenues or cost of sales, but interim statements generally disclose the accounts separately, often sparking concerns from investors, lenders and board members.”

What’s the solution? Ethanol plants that do not recognize forward contracts as derivative instruments on their financial statements may want to consider a change in their accounting methods. “They do have the option to treat those in the exact same manner as they are treating their other positions, which would be to mark those to market as well, so that you are actually showing true results in your financial statements,” King says.

Author: Holly Jessen

Associate Editor, Ethanol Producer Magazine

(701) 738-4946

hjessen@bbiinternational.com

Upcoming Events