Reining in Production - Hunkering Down as Margins, Supplies Rebalance

SOURCE: CHRISTIANSON & ASSOCIATES

April 11, 2012

BY Holly Jessen

The year 2011 turned out to be a good one for ethanol producers. Even with high corn prices the industry was profitable, especially in the fourth quarter, bolstered partially by record exports. Then, in December margins tightened dramatically, and ethanol stocks began to build, setting the stage for a whole new landscape.

As a result, margins were ugly in February and were shaping up pretty poorly in March, said Mike Chisam, president and CEO of Kansas Ethanol LLC, a 55 MMgy plant in Lyons, Kan. On the other hand, the good news is that margin structures can change for the better as rapidly as they fall, he added.

Production Reductions

In early February, ethanol industry giant, Green Plains Renewable Energy Inc., announced it was slowing production at two of its nine ethanol plants. Although the company didn’t specify which plants reduced run rates, it did identify those plants as the most inefficient facilities. Todd Becker, president and CEO of Green Plains, told EPM the company was evaluating the situation on a daily basis, determining if it needed to cut back at additional Green Plains plants, as well as when to return to full production. “It will last as long as we need to keep them lower, relative to the earnings power in those plants,” he said.

Green Plains was arguably the most notable example of an ethanol producer reacting to tight ethanol margins and high ethanol stocks by reducing run rates. While a handful of other ethanol plants also announced production reductions, experts agree many others were quietly doing the same without making the information public. “Everybody has got to at least be thinking about doing it,” said Donna Funk of Kennedy and Coe LLC. “Some are just at the point to take action quicker than others, due to different philosophies.”

While Kansas Ethanol LLC didn’t slow its production rates, the company did strategically go into its three-day spring maintenance shutdown early. And, Kansas Ethanol wasn’t the only one to make that move, Chisam said. The decision to shut down at the end of February instead of in March, as usual, came about because ethanol production was exceeding demand. “Ethanol plants just aren’t helping themselves by continuing to crank out product and putting it out in the marketplace,” Chisam said.

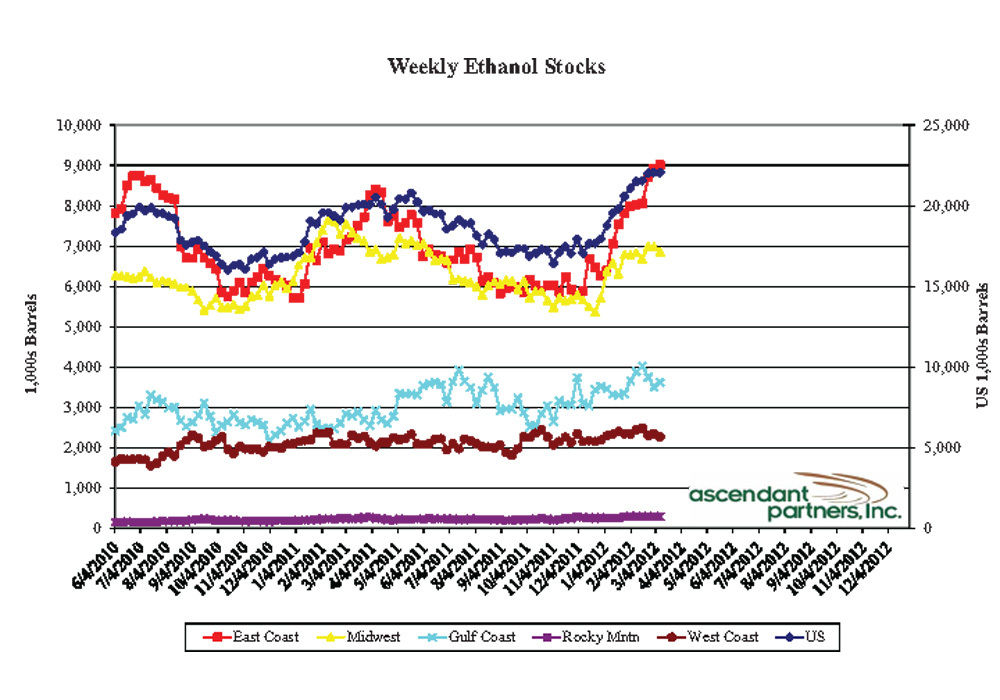

Although a 20-day supply of ethanol is less than 17 million barrels, ethanol stocks were well above that number at 22 million barrels in February and early March, according to information from the U.S. Energy Information Administration. The March 9 report showed that stocks went from what was at that time a high of 22.1 million barrels back down to 22 million barrels. As of the March 16 EIA report, however, stocks shot back up to a new all-time record of 22.7 million barrels—equivalent to a 27-day supply. Ethanol production averaged 896,000 barrels per day as of Feb. 24, 906,000 barrels per day as of March 2, 892,000 barrels per day on March 9 and 893,000 barrels per day as of March 16.

Rising ethanol stocks started at the end of 2011, when inventories were thin and margins were very attractive, prompting ethanol producers to churn out as much ethanol as possible. “When that environment changed in terms of demand, the industry was slow to react,” said Steve McNinch, CEO of Western Plains Energy LLC, a 50 MMgy plant in Oakley, Kan. “The industry had record production levels the last week of December the first week of January, at a time of extremely low demand.”

Advertisement

Independent of the “gross oversupply” of ethanol, the first quarter of the year is traditionally a time of tight margins for the ethanol industry. Gasoline demand, and therefore demand for ethanol for blending, slumps after the holidays and doesn’t typically pick back up again until the summer driving season hits, McNinch said.

So what’s the difference between this first quarter and other first quarters? It’s all about contrast. “We are running at about the same [profitability] level as we were last year at this time,” said Rick Kment, a Telvent DTN biofuels analyst. “We saw almost the highest margins ethanol have seen in recent history through the fourth quarter of 2011, so the challenge for ethanol producers is not that we are totally out of line from where we were in the past, but it was such a significant shift from where we were only three months ago,” he said in late February.

Kment saw that reflected in the Neeley biofuels hypothetical 50 MMgy ethanol plant, an internal company model used to gauge the health of the ethanol industry. DTN uses cash prices it tracks for corn and ethanol at the rack to calculate net profitability using various assumptions. The hypothetical ethanol plant has no capital debt and would most closely represent an older ethanol plant that started operating before the ethanol bust, he said. While no two plants are alike, the hypothetical plant on paper does give DTN a good measurement tool.

In October and November 2011 the hypothetical model showed a net profitability of 65 to 70 cents, he said. Compare that to the end of February, when the figure had dropped dramatically to a negative 27 cents in net profitability per gallon of ethanol, with a corresponding net operating profit of 4 cents. As of close of markets March 14, the numbers were changed for the better at negative 18.7 cents per gallon net profitability and a net operating profit of 13 cents per gallon.

That trend is likely to continue into spring and summer, said Scott McDermott, partner with Ascendant Partners Inc. “Once ethanol stocks come down over the next several months, the ethanol price will likely find more support as gas prices continue to rise, which will eventually result in better ethanol production margins,” he said in mid-March. “We are not out of the woods, but there is light at the end of the tunnel.”

Another potential release of the margin pressure valve for ethanol producers is the next corn crop. If the early growing season looks good, it could be a predictor of a healthy corn harvest. “If it appears to be abundant, I think you will start to see corn prices come down, which will immediately help margins,” Funk said.

What’s Gas Got to Do with It?

The New Year also brought with it a widening spread between gasoline and ethanol prices. As of the third week in November, reformulated blendstock for oxygenated blending (RBOB) and ethanol futures were virtually the same, Kment said. By the end of February RBOB was trading for $3.04 and ethanol $2.26—a 78-cent price spread. That gap continued to widen as gas prices kept rising and by close of markets March 14, $2.30 ethanol futures and $3.34 RBOB futures pushed the price spread to more than $1.

That attractive price spread has been promoting discretionary blending in the U.S. at the same time as export demand is also high, said Sander Cohan, analyst at ESAI Inc., which offers energy consulting services to ethanol producers and others. Those factors will continue to send a strong signal for ethanol in the marketplace. “What’s interesting is that although the prices will favor it, the demand for ethanol is limited by a weak gasoline market and also by limits on discretionary blending,” he added.

Advertisement

It’s not just a short term situation, either, McDermott said. Average annual gas demand is down more than 10 percent from peak demand in July 2007, according to EIA figures. In addition, projections are that gas demand will drop another 0.34 percent this year and will also be down slightly in 2013.

Although most experts agree low gas demand is a bigger factor, a rush to blend ethanol at the end of 2011—before the sunset of the Volumetric Ethanol Excise Tax Credit—did have an impact. “It’s not the major factor, but I think it’s a factor,” said Ron Lamberty, senior vice president with the American Coalition for Ethanol. Also the owner of two retail gas stations in South Dakota, Lamberty says he has definitely heard of cases where blenders were purchasing larger amounts of ethanol to ensure they’d get the 54-cent tax incentive before it went away. For some the gamble didn’t pay out. “As it turned out, the price of [ethanol] dropped enough that if they bought it early or middle December they probably lost money on the deal,” he said.

In order to take advantage of VEETC, blenders needed two things: to also be a fuel retailer, and to have plenty of storage capacity. Before VEETC expired, Internal Revenue Service-issued guidance said that blenders who sold their own fuel could collect the tax incentive when it was blended, even if it wasn’t physically at a retail fueling station, Lamberty said.

That kind of vertical integration is what gives some ethanol producers a distinct advantage over others, said Don Roose, president of U.S. Commodities, a West Des Moines, Iowa, brokerage company that advises ethanol plants. Ethanol plants operated by petroleum companies, such as Valero Energy Corp. and Murphy Oil Corp., can continue to blend ethanol to meet blending requirements, even if margins tighten up at their ethanol facilities. Nonvertically integrated ethanol plants, on the other hand, have to take a look at other options, such as throttling back on production levels.

Crystal Ball

Although there’s no crystal ball guaranteeing the future, many experts believe the ethanol industry will make it through current tough times. Tight margins for two or three months—especially following strong margins in the late third and fourth quarters—won’t be enough to cause huge distress in the industry, says Green Plains’ Becker.

Kment agrees. “From all appearances now, this is more of a controlled risk management issue, versus a total panic in the market, so I think that’s going to continue to help to stabilize the market long term,” he says.

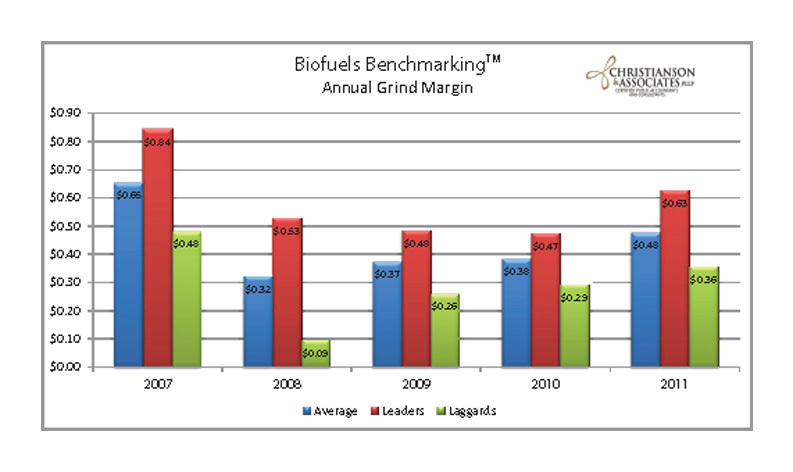

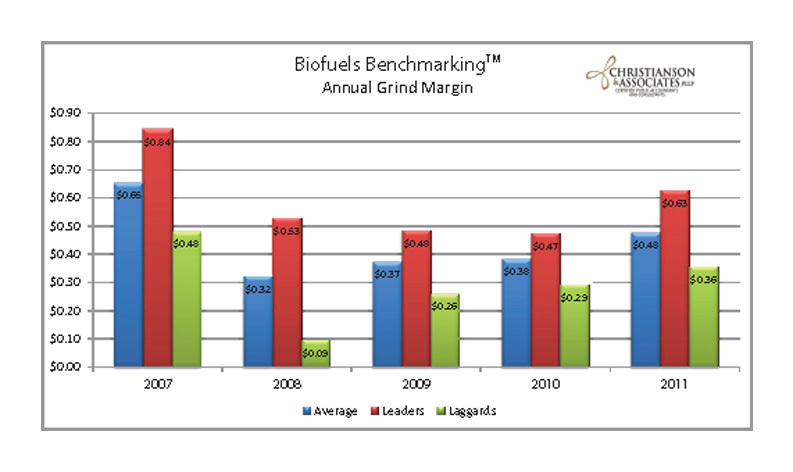

It’s possible there could be a few bankruptcies and it could lead to more consolidation in the industry, Funk says. But it won’t be anything like what happened in 2009. Most ethanol plants today are better situated financially to survive a period of tight margins, having paid down debt. Back in 2008, when corn prices shot up, and in 2009, the time of multiple bankruptcies, there were more brand-new plants that were thinly capitalized and heavy on debt. “Some of them were plants that probably never should have had money loaned to them to start with,” she says.

As the industry continues to mature, Kment predicts more ethanol plants will model themselves after the ebbs and flows of the animal packing industry. While that industry is producing constantly, rates fluctuate based on seasonal demand, to maximize profits and minimize losses. He believes the ethanol industry will begin to develop its own model of this, rather than running at full production rates year round. The industry will also begin to take a longer-term approach to its contracts for ethanol and distillers grains, depending on seasonal patterns. “I do expect that to be a little bit more of a fluid movement in overall demand than what we have seen in the past,” he said.

Author: Holly Jessen

Associate Editor, Ethanol Producer Magazine

(701) 738-4946

hjessen@bbiinternational.com

Upcoming Events