Setting the Net

June 10, 2011

BY Kris Bevill

Recently it’s been difficult to navigate a 24-hour news cycle without hearing at least some mention of the U.S. deficit. Discussions of the nation’s debt have dominated the political scene at the national and state levels as governments struggle with the task of regaining positive growth after a difficult economic recession. The situation has made the ethanol industry an easy target for those seeking ways to reduce government spending. The Volumetric Ethanol Excise Tax Credit and ethanol import tariff have been on some legislators’ chopping blocks for several years, and their repeated attempts to entirely eliminate the programs have been consistently defeated, but after December’s last-minute, one-year extension of both provisions, it was made clear that even pro-ethanol legislators would no longer support the continuation of VEETC or the import tariff at their current levels beyond 2011. Ethanol industry groups consented and agreed to combine their efforts and work with lawmakers to form a long-term reform plan for VEETC. By late May, the ethanol industry’s official long-term road map had yet to be unveiled, but recently introduced legislation offers a feel for what the industry’s preferred modifications look like.

On May 4, Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, introduced the Domestic Energy Production Act of 2011, which he offered as “a good starting point” for ethanol tax policy reform. The bill recommends reducing VEETC from its current rate of 45 cents per gallon to 20 cents per gallon beginning in 2012, and reducing it again to 15 cents per gallon in 2013. Beginning in 2014, the credit would become a variable tax credit, allowing ethanol blenders to claim a 30-cent-per-gallon tax credit during times when oil prices are $50 per barrel or less. For those times when oil prices range from between $50 per barrel and $90 per barrel, the credit would vary based on the price of crude oil. If oil prices are $90 per barrel or higher, there would be no ethanol tax credit because blenders would have enough market incentive to participate in discretionary blending without additional tax credits. The import tariff would follow the blenders’ credit, but would not vary after 2013 and instead remain steady at 15 cents per gallon.

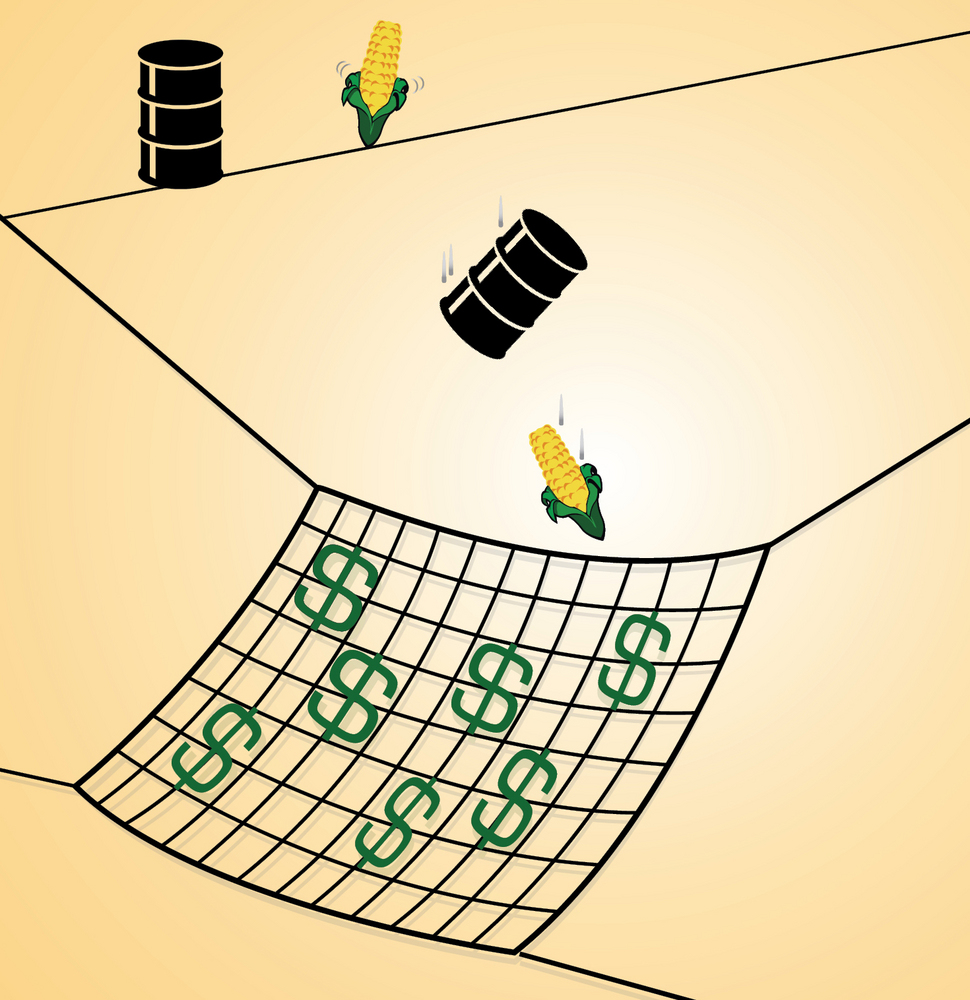

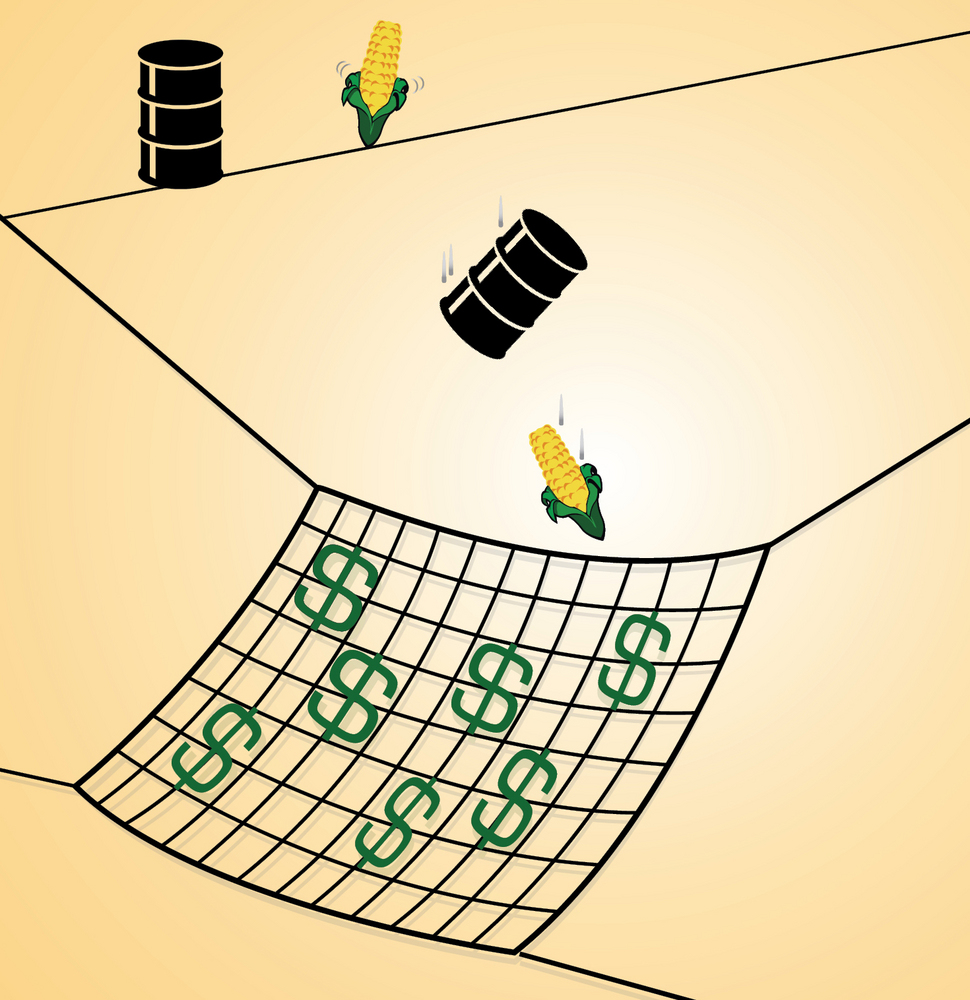

Safety Net

The concept of a variable tax credit for ethanol blenders has been floated around for some time, according to those familiar with efforts to modify the program. Initially, there was some skepticism as to whether the program would be too cumbersome or novel for the concept to gain widespread acceptance. However, there are other instances of this type of program being used, most notably in the agriculture industry in the form of deficiency payments for corn farmers in years past, and the notion of a variable incentive has now become the preferred option for reform among ethanol industry groups.

Wally Tyner, energy economist and professor of agricultural economics at Purdue University, is known as the foremost researcher of the variable tax credit approach and says it represents an efficient option to reduce both government financial obligations and private sector risk when compared to the current VEETC. “That’s the real advantage of this,” he says. “There’s a win-win zone where government outlays go down, but private risk also goes down.” A variable credit based on oil prices, such as was proposed by Grassley, offers no support when prices of oil, gas and ethanol are high, because none is needed, Tyner says, adding that the credit would basically exist to provide producers with a safety net for times when oil prices are low.

Geoff Cooper, vice president of research and analysis for the Renewable Fuels Association, admits that the term “safety net” as related to agriculture policy has had negative connotations in the past, but he says the term fits when describing the variable ethanol tax credit concept. “That’s the idea here,” he says. “It’s a backstop to ensure that at times when oil prices are low, ethanol blenders downstream will continue to have an incentive to blend as much ethanol as possible.” The RFA has been committed to exploring the possibility of a variable tax credit since it became obvious that VEETC wouldn’t be extended in its current form, Cooper says, and believes it to be the most attractive option for reform. “It can work and we’re excited by the prospect of having a variable credit and think it will provide assurance when the oil market crashes,” he says.

Considering the current run-up in oil prices and the number of institutions that have predicted high crude oil prices for the foreseeable future, an obvious question is whether it is even necessary to implement a program to protect ethanol against low oil prices. Cooper believes it is. “People forget that when the commodities bubble of 2008 burst, oil prices crashed, and they crashed hard—to less than $40 per barrel of oil,” he says. “At that point, we saw ethanol prices higher than gasoline and, had the VEETC not been in place at that time, you certainly would have seen a decrease in discretionary blending. That’s exactly the type of scenario that this type of program is intended to protect against.”

Tyner says that while oil prices probably will not go down, the possibility is there. “I’m not saying it’s the most likely scenario; it’s not,” he says. “The most likely is that it will stay in this $90 to $100 range, in which case there’s no subsidy. But in the event of another recession or another giant oil field find, the safety net is there.”

Other Options

While Grassley’s proposal suggests basing the variable ethanol tax credit on crude oil prices, there are other market factors that could also be used to trigger a variable incentive. Economists at the University of Illinois recently released a paper exploring the viability of a variable ethanol blenders tax credit and concluded that using crude oil as the trigger may not always be beneficial. Because crude oil is used to produce a wide variety of products, the price of crude is not always related to the blender’s margin, the authors wrote. Basing the credit on gasoline prices, specifically Reformulated Blendstock for Oxygenate Blending, may be a better option because it would eliminate the influence of those other factors. An even better choice, however, might be to base the incentive on the blending margin, which could be calculated monthly by subtracting the previous month’s wholesale ethanol price from the wholesale gasoline price. “The level of crude oil prices is not perfectly correlated with blending margins,” says Scott Irwin, professor of agricultural economics at the University of Illinois and co-author of the analysis. “It’s possible you could have higher crude oil prices, but ethanol above gasoline prices, and you wouldn’t be getting a subsidy under the crude-oil based variable policy. But you would under the blending margin proposal.” Basing the tax credit on the blending margin would also reduce the government’s outlays even further than if it were based on crude oil, Irwin says, because the incentive would likely come into effect in fewer instances.

Another option for VEETC reform was introduced earlier this year by Sens. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., and Tim Johnson, D-S.D. The Securing America’s Future with Energy and Sustainable Technologies Act would immediately reduce the credit to 20 cents per gallon beginning next year and then simply ratchet it down by 5-cent increments annually until the credit zeroes out in 2016. Money saved from the evaporating blenders’ credit would be diverted toward biofuels infrastructure expansion. Johnson says that while VEETC has played an important role in assisting the domestic biofuels industry gain a foothold in the marketplace, he believes this option would serve to reform and reduce the tax credit as needed, while also making necessary investments in infrastructure. Grassley’s proposal, meanwhile, does little to address infrastructure expansion.

Growth Energy was the lone ethanol industry group to publicly endorse the Klobuchar-Johnson proposal. Grassley’s proposal received the backing of an ethanol alliance including Growth Energy, the RFA, the American Coalition for Ethanol and the National Corn Growers Association. Growth Energy CEO Tom Buis says his group spoke out in support of a variable tax credit program last year, but that the group also believes a greater emphasis should be placed on confronting infrastructure constraints. “Almost anyone you talk to in the industry is really about clearing those infrastructure barriers by getting more flex-fuel vehicles on the road and combining that with flex pumps at the nationwide retailers so that the American consumer can choose the blend they want,” he says. “The tax policy is important. I’m not saying it’s not. But right now we don’t have that distribution mechanism. We don’t have the cars capable of a wide range of blends. Those two, I think, is where you’re going to see Growth Energy continue to keep its focus, because that’s our future.”

There are risks and concerns with any type of incentive program. For ethanol incentives, the major concern is how they might affect corn prices. This can be extremely difficult to quantify, according to economists. “It’s a really tough question because it depends on what you want to assume,” Tyner says. “If the blend wall is still there, it doesn’t really matter because not much would get to the producer anyway.” In a scenario where blend wall restrictions are eliminated, a variable credit could relieve some pressure on corn prices when the incentive is not in effect. Irwin says a reduction from the current VEETC rate could have some effect on corn prices as the impacts of a lesser incentive filter down to corn farmers, but it likely would be minimal. “There’s some risk that it would lower on average the price of ethanol and therefore lower the price of corn as well,” he says. “But I think the magnitude of those impacts is hard to assess because we don’t have them pinned down very well for the current 45-cent program.”

Irwin says the most likely participant in the ethanol production chain to be affected by a change to the tax credit program are the blenders themselves. “They haven’t been forced to confront the true cost of the biofuels mandates as it relates to ethanol because of VEETC,” he says. A variable incentive makes possible a scenario in which blenders may be required by the renewable fuel standard to use ethanol at a loss. The current VEETC appears to make up for that loss, but that is not guaranteed under variable incentive program.

Tyner says his only concern regarding a variable tax credit is its potential impact on the renewable identification numbers (RINs) markets. “My view is that if it were done instantly, it would be disruptive early on of the RINs market,” he says. “But markets adjust. Once people figure out that all it means is they need to take into consideration oil futures in the thinking about RINs—do we need to buy more? sell more?—markets can and would do that. It just might take them a little while to learn how to do it.”

Reforming Reform

One main point politicians and ethanol group representatives all make clear is that the Grassley bill, as well as any other option on the table for VEETC reform, is not a final offer. Johnson, for example, says that while he believes in his proposal for reform, he’s not opposed to entertaining other options. “I am open to different approaches to reforming the tax credit and I have worked with my colleagues to develop various legislative proposals that will be part of the debate on energy policy,” he says. “Ethanol plays an important role in our transportation fuel mix and has been shown to keep gas prices lower than they would otherwise be. Particularly as gas prices are skyrocketing, we should not haphazardly pull support for ethanol with no fall-back but greater oil dependence.”

The general consensus among industry supporters is that tax credit support for ethanol should not be entirely eliminated in one fell swoop, but the concept of a gradual shift to a variable program, as suggested by Grassley, has not been whole-heartedly embraced either. “If a variable tax credit makes sense, it makes the most sense to go to it right away,” Irwin says, adding that there is no economical reason to fix the price for two years. Tyner agrees that the decision to ease into a variable program is entirely a political decision, and says he doesn’t have a strong feeling toward implementing the program now versus two years from now, as long as the industry has some time to prepare for whatever change is headed its way.

Ethanol groups appear to now be focusing on doing some of their own blending, hinting that provisions from several of the ethanol reform bills could be included in a comprehensive energy package. Buis says the delay in implementing the variable tax credit as proposed by Grassley would offer the industry and lawmakers time to hammer out the finer details, such as the preferred incentive trigger. Cooper says the RFA is very happy with Grassley’s bill because it achieves its goal of addressing ethanol tax policy. He mentions other legislation, such as the Open Fuel Standard proposed by Rep. John Shimkus, R-Ill., as presenting opportunities for infrastructure expansion. It’s unlikely that any of these pieces of legislation have a chance of being approved on their own, but Cooper believes Congress is inching toward considering a comprehensive energy bill, which would improve the chances for a number of the ethanol-related provisions to pass. “When we look at the fact that we’re paying $4 for gas, and probably on the way to $5 for gas, that’s really going to light a fire under Congress to take a hard look at our energy policy and see what things can be done to move us in a better direction,” he says.

Author: Kris Bevill

Associate Editor, Ethanol Producer Magazine

(701) 540-6846

kbevill@bbiinternational.com

Advertisement

More Options

It appears likely that some type of variable tax credit will eventually be used to replace the current fixed-rate Volumetric Ethanol Excise Tax Credit. However, according to Wally Tyner, energy economist and professor of agricultural economics at Purdue University, there are several other options for VEETC reform. Some of the more interesting options include:

• Shifting the credit from the blender to the biofuel producer. Under this option, ethanol producers would receive the tax credit, but Tyner cautions that they wouldn’t necessarily retain the benefit because ethanol prices would still be determined by supply and demand. Therefore, what would appear to be an improvement for the producer would “likely result in no change,” he says. A method would also have to be developed to ensure that ethanol receiving the credit is not exported, a concept that could be very difficult to implement.

• Providing a credit only for the quantity of ethanol produced in excess of the renewable fuel standard. This option would substantially reduce the government’s financial requirements, but would have no impact on corn prices, according to Tyner. A program of this type could be implemented through the renewable identification (RIN) markets.

• A credit based on the energy content of the fuel produced. Basing an incentive on the fuel’s energy content, rather than the volume, would be a more technology-neutral approach and would level the playing field among biofuel technologies, Tyner says. The U.S. EPA uses a similar approach for RINs.

• A credit based, at least partially, on the facility’s reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. This approach could provide an overall environmental benefit by rewarding producers for reducing their carbon footprint. However, implementing a program of this type could be quite costly as it would require the certification of each ethanol facility’s carbon footprint.

Advertisement

Upcoming Events