Water: Reduce, Reuse and Recycle

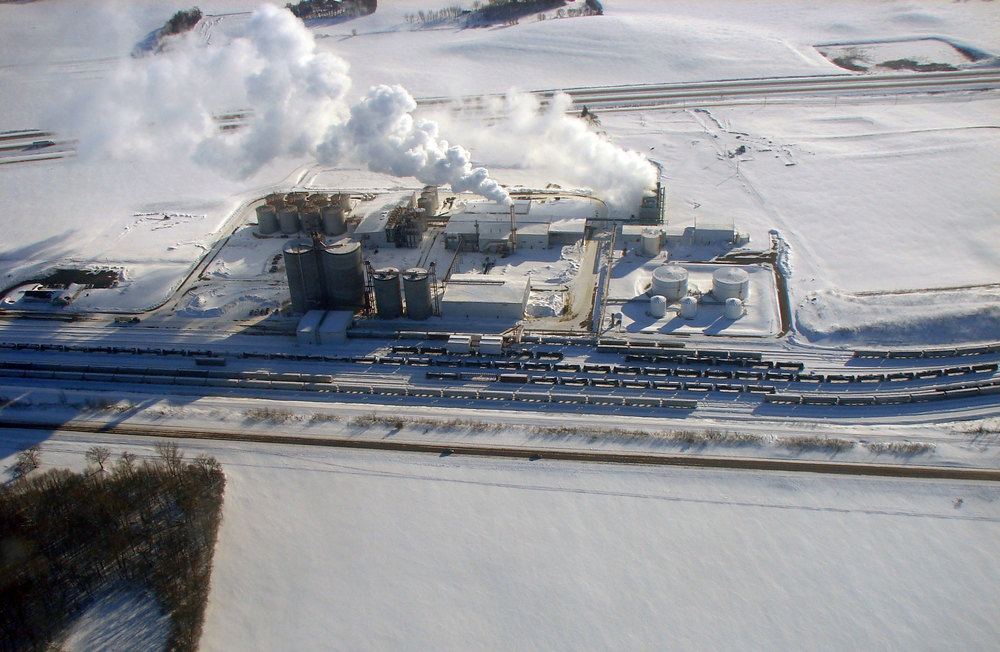

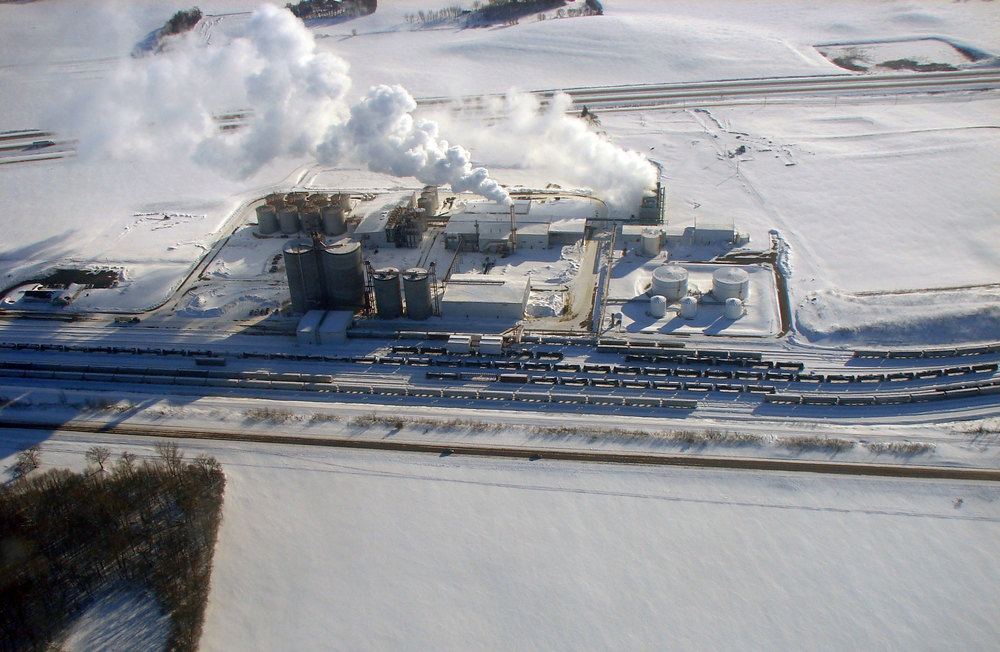

PHOTO: GUARDIAN ENERGY

May 13, 2011

BY Holly Jessen

Water conservation is a top priority for Poet LLC, which recently surpassed Archer Daniels Midland Co. as the largest ethanol producer in the U.S. “Fresh water is a precious natural resource that we do our utmost to conserve,” says Jeff Broin, CEO of Poet. “We have seen tremendous efficiency gains in the 23 years I’ve been in this business, but we can and will continue to do better.” In March 2010, Poet said it would aim for a 22 percent reduction in water use across all its facilities by 2012. The company, which today includes 27 production facilities with a combined 1,696 MMgy of ethanol production, is aiming for an average of 2.33 gallons of water per gallon of ethanol produced.

Industry wide, the amount of water it takes to produce ethanol has decreased steadily over the years. The latest numbers, taken from a 2010 report by Steffen Mueller of the University of Illinois at Chicago, reveal that on average, a dry mill corn-ethanol plant in 2008 used 2.72 gallons of water to produce one gallon of ethanol and discharged 0.46 gallons of water. The survey also revealed that ethanol producers are continuing to consider installing more efficient water use technologies.

To produce corn from ethanol, water is required for grinding, liquefaction, fermentation and separation as well as process water, cooling water and steam generation for heating and drying, according to the Argonne National Laboratory, “Water Consumption in the Production of Ethanol and Petroleum Gasoline,” published in 2009 in the Journal of Environmental Management, the most current study available. Water losses happen during evaporation, drift, blowdown from the cooling tower, deaerator leaks, boiler blowdown, evaporation from the dryer and incorporation into ethanol and DDGs. By far, the heaviest water users are the cooling tower, which accounts for 53 percent, and the dryer, which accounts for 42 percent.

Those numbers show that alternative cooling technologies would be a good place for further research, says Andy Aden, senior research engineer for the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. There are existing technologies, such as dry cooling or air cooling, offering opportunities for significant reduction. “Unfortunately, those tend to come with a trade-off, which is increased cost,” he says.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The Argonne report identified several areas for potential water reduction measures at ethanol plants, including increasing process water recycling by such methods as capturing water vapor from the dryer and recycling boiler condensate; increasing cycles in the cooling tower; or recycling treated process water and/or cooling tower blowdown. If those measures were coupled with steam integration, water intensity can be reduced even more. “The ethanol industry maintains that net zero water consumption is achievable by water reuse and recycling using existing commercial technology and with additional capital investment,” the report says.

Michael Webber, associate director of the Center for International Energy & Environmental Policy, offers ethanol producers another reason to conserve water. Although not many make the connection, he says, water is needed to generate energy, such as at a power plant or ethanol plant, and energy is needed to deliver clean water. “Many people are concerned about the perils of peak oil—running out of cheap oil,” he says in a 2008 article he authored for Scientific American. “A few are voicing concerns about peak water. But almost no one is addressing the tension between the two: water restrictions are hampering solutions for generating more energy, and energy problems, particularly rising prices, are curtailing efforts to supply more clean water.”

Ethanol producers are very aware of the water conservation issue. Overall, the industry has reduced water use 48 percent in less than 10 years, the Argonne report says. Poet isn’t the only example of an ethanol producer that is applying the “reduce, reuse and recycle” principle to water consumption. Other producers on the cutting edge of water conservation include a North Dakota plant that uses wastewater for 100 percent of its water needs and a Minnesota plant that got tough on water discharge.

Waste Not Water

When the site in Casselton, N.D., was selected for Tharaldson Ethanol LLC, it was because it had good access to corn and energy, as well as rail and road transportation infrastructure. The weakness was water supply, says Russ Newman, vice president of public relations and governmental affairs for the 150 MMgy ethanol plant.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The company started the process to get permission from the North Dakota Water Commission to drill wells at one of the nearest aquifers. Not only are the aquifers located 20 or more miles away, but there was no guarantee Tharaldson would get approval after going through the long process of required public hearings. That’s when the idea of using wastewater from Fargo started looking more attractive than wells that would be tapping into the same groundwater used by some area farmers to irrigate the corn they’d be selling to the ethanol plant. “We thought, why fight with those farmers for that same water, when we can recycle city wastewater?” Newman says.

It’s an elegant solution for all parties involved. Not only does the ethanol plant reuse wastewater that would typically be treated and discharged into the Red River, but it generates income for the City of Fargo and Cass Rural Water rather than sucking up groundwater, says Jerry Blomeke, general manager of the Cass county system, which completed the project cooperatively with Tharaldson and Fargo.

The $15.3 million project included building a wastewater treatment plant and installing 26 miles of underground lines, with 12-inch pipe used for pumping water to the ethanol plant and a 4-inch line returning to Fargo. First, Fargo treats its wastewater at the city’s wastewater treatment facility. Then, about 10 percent of the water it would normally discharge into the Red River is diverted to a separate water treatment plant where it undergoes microfiltration and reverse osmosis in preparation for use at the ethanol plant, Blomeke tells EPM. Cass Rural Water purchases the water from Fargo and sells it to Tharaldson for $2.92 per thousand gallons, which works out to 0.03 cents a gallon.

The Tharaldson facility produces about 400,000 gallons of ethanol a day using 1 million gallons of water in the summer and about 800,000 gallons in the win ter. One of the sweetest things about the project, Newman says, is that of the water used at the ethanol plant, about 15 percent is returned to Fargo as gray water, where it is retreated to drinking water standards. Of the total amount of water the plant receives from Fargo, it uses about 2.7 gallons of water per gallon of ethanol produced. However, looking at only the net water usage, subtracting the amount sent back to Fargo for reuse, the plant uses around 2 gallons. To achieve that, the plant reuses the water it gets from Fargo as much as it can until it is piped back to the city, Newman says.

Cass Rural Water financed the construction of the project with a loan through the North Dakota Public Finance Authority, Blomeke says. It then turned over the water treatment plant to Fargo, which operates and maintains it. The pipes are operated and maintained by Cass Rural Water. Fargo’s portion of the project is about $1.6 million, which it pays back from the money generated by selling water to Cass Rural Water. In all, Tharaldson will pay back about $13.8 million of the loan, in addition to the fees it pays for water, he says.

All in all, Tharaldson ethanol is pretty pleased with how the project turned out. It cost more than drilling wells would have, Newman says, but it just made sense in the long term. Besides reducing the impact to the environment by using wastewater, the ethanol plant also eliminated the need for a lagoon, which can cause odor issues. “That’s another big strength here,” he tells EPM.

A Little ‘Ingreenuity’

Poet’s water conservation efforts are part of its Ingreenuity initiative, a sustainability effort to reduce its water use by 22 percent in five years—or about one billion gallons saved across all its plants by 2014. That translates into an average of 2.33 gallons of water per gallon of ethanol produced, down from an average of 3 gallons. “If we can surpass that goal, by all means, we will,” says Erin Heupel, director of environment and technology, public policy and corporate affairs for Poet.

Poet engineers developed a proprietary process called Total Water Recovery, which recycles cooling water rather than discharging it. When the announcement was made, the system had already been installed in three Poet plants in Bingham Lake, Minn., Caro, Mich., and Hudson, S.D., where it reduced water use to an average of 2 to 2.5 gallons of water per gallon of ethanol. One year later, 13 of Poet’s 27 plants have adopted the water conservation measures, resulting in more than 400 million gallons of water savings compared to the company’s 2009 water use levels, Heupel tells EPM. Ingreenuity isn’t the first of Poet’s water conservation efforts, however, as it began working to reduce water use in 1988. “The first Poet plants used 17 gallons of water per gallon of ethanol, so it’s part of the learning curve and the continual push to improve,” she says.

Beyond just reusing water within the plant, two Poet plants recycle water used by nearby industries. In Portland, Ind., the Poet plant uses water from a limestone quarry for 100 percent of its water needs. Instead of being pumped into the river, the water goes to settling ponds before being used at the 73 MMgy ethanol plant. In Big Stone, S.D., the 81 MMgy Poet plant gets 80 percent of its water from the cooling ponds of a power plant. “You are getting a lot of use per gallon of water, because it is running through two industries,” Heupel says.

Other water recycling efforts include the use of treated effluent from the Corning Waste Water Treatment Plant for cooling water at the 73 MMgy Poet plant in Corning, Iowa. Previously, that water was discharged into the river. The idea originated with city officials before the plant was built and Poet was glad to cooperate. “We knew that water would be a challenge for the community,” she says.

Just as it did with its corn-based ethanol production facilities, Poet will continue water conservation efforts with the next generation. Project Liberty, the company’s first commercial-scale cellulosic ethanol plant, is scheduled to start operating in early 2012, using corn cobs, leaves and husks as the feedstock. The 25 MMgy plant is in the design phase, Heupel says, and will be built in Emmetsburg, Iowa. Although the plant will use Poet’s water recovery system, it will likely use more water than corn-ethanol production because cellulosic ethanol is still new. “Using what we’ve learned, some with the corn ethanol process improvements, they’ll roll as much of that as they can into the cellulosic ethanol process improvements,” she says.

Reducing water use at an ethanol plant could save producers money but it also costs money to save water. For example, Heupel says, the company had to pay to install the settling ponds at its Portland plant. For Poet, it’s about water conservation, not saving money. “Ethanol is a renewable fuel,” she says. “I think if you don’t look at your entire environmental footprint, you’re missing the importance of the renewable fuel.”

Poet isn’t limiting its work to its own 27 production facilities. First, the company wants to make its Total Water Recovery process available to other ethanol producers. It also plans to survey corn producers that deliver feedstock to its plants to nail down exactly how much is irrigated. Finally, the Poet Foundation has also promised more than $420,000 to help the non-profit Global Health Ministries to repair, construct and maintain 90 wells in Nigeria, giving more than 300,000 people access to pure water.

Guardians of Water

In 2009, Guardian Energy LLC’s first year of operation, the 100 MMgy ethanol plant used an average of 3.6 gallons of water to produce 1 gallon of ethanol. In late 2010, the company worked with U.S. Water Services to install a proprietary system that shaved more than 1.6 gallons of water off that number. The project wrapped up in early February. “We’ve seen an overall reduction of about 38 percent,” says Tom Hanson, vice president of operations for the Janesville, Minn., plant.

The plant, which utilizes groundwater, has always been considered a zero process liquid discharge, meaning water that came into contact with any part of the ethanol process was not discharged. Two other water uses, however, were discharged those being the water from cooling tower blowdown and reverse osmosis water, the process used to purify water for the heat exchanger and boiler. “With our new technology we no longer discharge that water,” Hanson says.

The water conservation system cost Guardian less than $100,000 to install and is already saving the facility money—reducing the cost for sampling and chemical treatment of discharge water. In addition, the company is saving money on phosphorus credits, which the State of Minnesota requires of plants that discharge water. “It’s definitely a cost savings on a daily, yearly basis,” Hanson says.

Still, it’s not really about the money for Guardian either. Reducing water use at the ethanol plant helps the plant be good neighbors in its community and be good stewards of the environment. “The major reason (for installing this), first and foremost, was water conservation,” he says.

Overall, the company feels it is important to identify areas of concern with ethanol production and then attempt to address them. Water conservation, energy conservation and increased efficiencies are all part of that, as Guardian Energy continues to evaluate new technology coming to the forefront, he says. CEO Don Gales echoes that thought. “Guardian Energy is committed to being a leader in the industry and continues to look towards technologies that will allow for higher yields and increased efficiencies,” he says. “The implementation and execution of this technology is consistent with Guardian Energy’s commitment to the community, environment and the industry.”

Ethanol, Oil Compared

When ethanol skeptics start talking about the amount of water used to produce a gallon of ethanol, it would be nice to hit back with stats about how much water is used by the petroleum industry. That’s not easy to do, however.

The problem is picking a number. Various sources offer up anything from 2 gallons of water used per gallon of gasoline produced, all the way up to 25. That’s because many doing the analysis use different parameters and methods, Aden says. Does the number include water used in oil production/extraction and exploration? Or does it include just the water used in the refining process, or both?

Oil production and exploration is the major water user, while refining gas from crude uses less, according to the Argonne study. Looking at combined numbers for crude extraction and refining, water use depends on the recovery method and region. For U.S. offshore oil, the study gives a range of 3.4 gallons to 6.6 gallons water used per gallon of gasoline produced. Canadian oil sands numbers range from 2.6 to 6.2 gallons, while conventional oil from Saudi Arabia is estimated at 2.8 to 5.8 gallons.

On the biofuels side, the report considers both irrigation to grow corn, as well as the amount of water used to produce ethanol, resulting in a higher number than generally cited by the ethanol industry. The report concludes that nearly 70 percent of ethanol is produced with 10 to 17 gallons of water used to produce each gallon of ethanol. Cellulosic ethanol is estimated at a range of 1.9 to 9.8 gallons of water. Ethanol production facilities are increasingly less water intensive, the report notes, excluding the issue of irrigated corn. On just the fuel production side, the report says an average of 3 gallons of water is used to produce 1 gallon of ethanol, citing a 2007 Renewable Fuels Association survey of existing ethanol plants.

An updated Argonne report is currently being worked on, says May Wu, one of the authors, that will contain new figures reflecting water conservation efforts in both the ethanol and petroleum industries. In addition, it will also consider precipitation as well as irrigation to show a more complete water-footprint analysis. Although water used in irrigation and precipitation are different types of water, both evaporate and go through the hydrological cycle, eventually returning to earth again. “Not to your local area though,” Wu tells EPM. “To another area, usually. Look at the wind—it goes northeast from southwest.”

Talking about irrigated corn being used to produce ethanol can be misleading for the public, who may assume all or most corn is irrigated, Heupel says. According to the National Corn Growers Association, only 11 percent of the total corn crop was irrigated in 2010. Wu acknowledges this too, pointing out that a large portion of ethanol production happens in the Midwest, where rainfall is ample and little irrigated corn is raised.

Examining water use statistics can be tricky, Aden cautions. Are they talking consumptive water or water footprint, which as Wu mentions, includes a full life cycle from growth to production? Adding precipitation to water use figures could give a more complete picture, as Wu says, or it could make biofuels look like a major water hog, even though many of those gallons are part of the natural cycle of rain, evaporation and back to rain again. “If you look at it in certain perspectives it does favor fossil fuels,” Aden says.

For example, a water use comparison cited by Webber claims it takes 130 to 6,200 gallons of water for a flex-fuel vehicle to travel 100 miles. Compared to those numbers, plug-in electric vehicles look great at only 24 gallons per 100 miles and gasoline vehicles look even rosier at 7 to 14 gallons. He sees some positives for biofuels but feels there are some potential problems to watch out for—such as water use. “Whether proponents realize it or not, any plan to switch from gasoline to electricity or biofuels is a strategic decision to switch our dependence from foreign oil to domestic water,” he says.

On the other hand, Aden says the studies he’s seen show there should be enough water for biofuels production. Some drier areas of the U.S. will have limitations on water availability. But where corn ethanol may not be appropriate, a feedstock such as sorghum might. “By and whole, I think people expect there’s going to be enough water for biofuels,” he says, “even if biofuels continues to grow.”

Another thing to keep in mind is that water conservation is an important issue for many industries, and not just ethanol. It takes a lot of water to produce and process everything from newspapers to meat. “I think that’s one of the things we need to strive to do, is keep everything in perspective,” Heupel says. “If you look at something in isolation, and you don’t have anything to compare it to, you get things really out of kilter.”

Author: Holly Jessen

Associate Editor of Ethanol Producer Magazine

(701) 738-4946

hjessen@bbiinternational.com

Upcoming Events