Affirming Sustainability

Photo: Stock

November 28, 2022

BY Katie Schroeder

The pellet industry is no stranger to accusations from environmentalists that the fiber it uses is not sustainable or is handled irresponsibly. Recently, the Wood Pellet Association of Canada took action to prove these claims are false and combat misinformation with the facts. Gordon Murray, executive director of WPAC, explains that organization commissioned the study in response to articles in environmental publications with photos of logs at pellet plants, accusing the industry of turning whole logs into fuel. “They were also accusing us of doing dedicated harvesting on a large scale of forests in order to make wood pellets,” he says. “And both of those were false, but we knew that people would suspect whatever the industry would say. So, we wanted to get an independent group to report on what we are actually doing.”

Bull & Bull Consultants performed the study, which entailed a combination of examining and cross-checking data as well as conducting interviews. “They examined log scaling data from all across British Columbia, essentially looking at every load that had been taken into pellet plants over a period of time, and then analyzed and compared it with audit reports from the Sustainable Biomass Program. They did a bunch of cross-checking and then came to report conclusions,” Murray says.

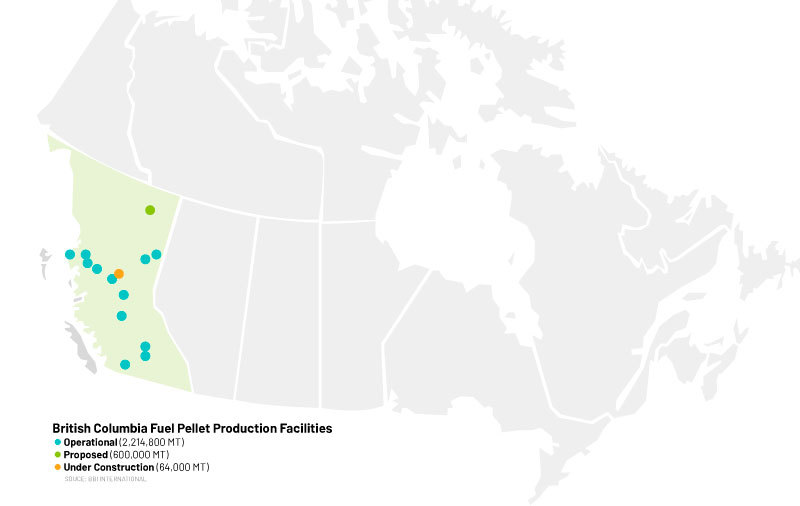

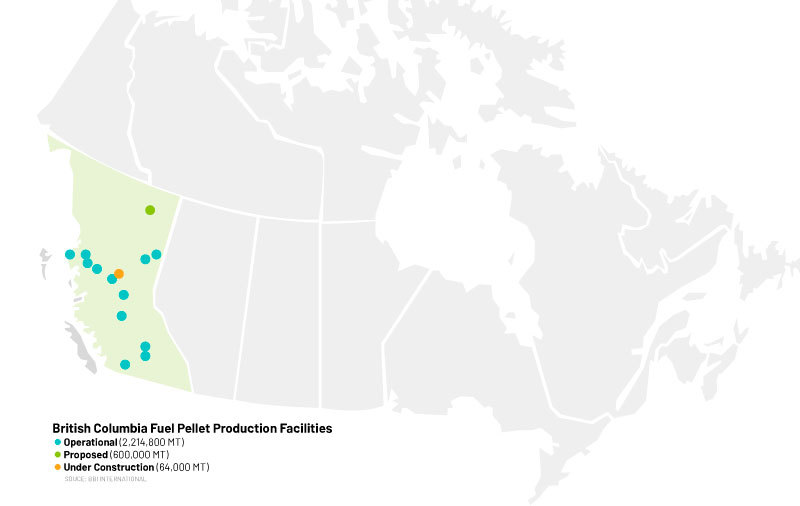

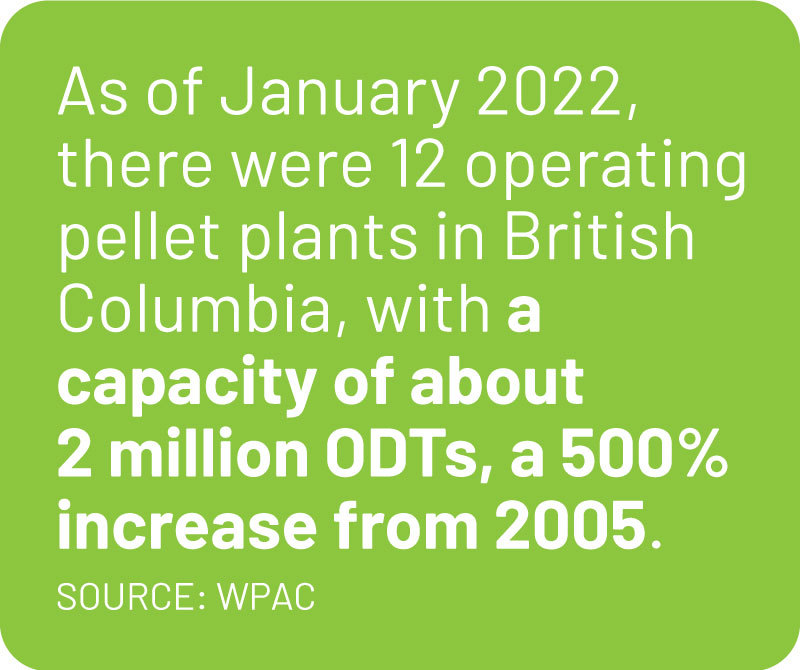

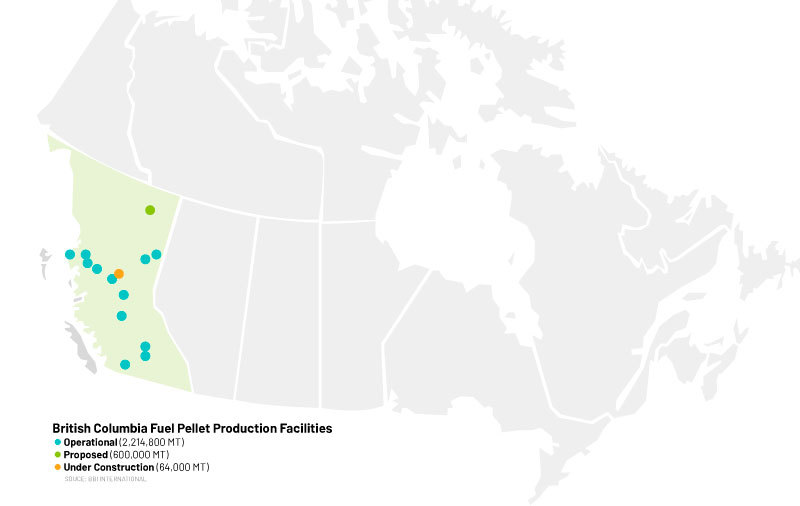

The study analyzed the feedstock source of sawmills in British Columbia for a few reasons, Murray explains. British Columbia has the highest concentration of pellet mill plants in all of Canada, containing 60 to 70% of the country’s production capacity. The second reason was that the accusations were targeted at plants in that area. And finally, the data in that province was all in the same format and was easily accessible. The researchers found that 85% of the biomass material was mill residue and 15% was forest residue, with the forest residue breaking down into 11% low-quality roundwood and 4% bush grind. “Essentially, we confirmed that all the fiber being consumed by the province comes from residues produced by either other mills or from leftover wood from forests,” Murray says.

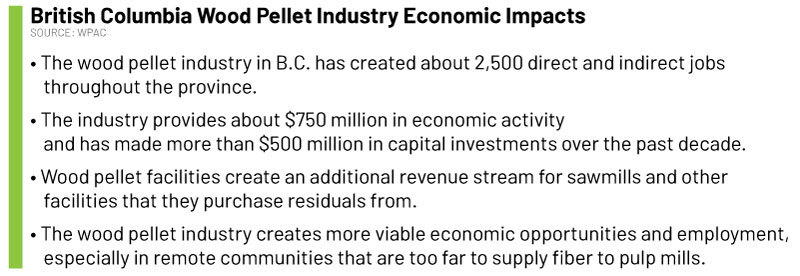

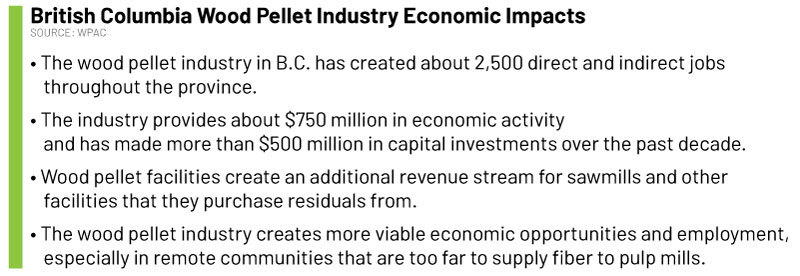

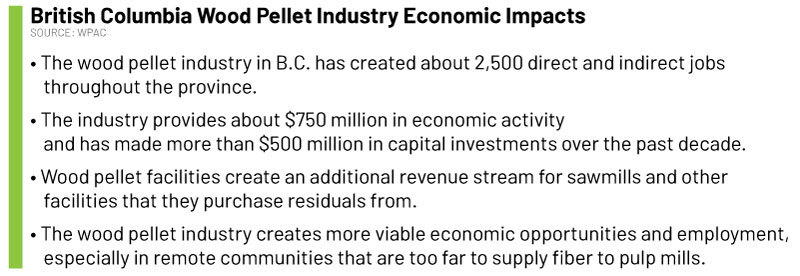

“It confirmed that we work in cooperation with indigenous and other communities to improve forest health and support the local economy, and that our fiber sourcing creates an extra revenue stream for sawmills, so it helps the viability of the sawmill industry.” Demonstrating that everything harvested from the forest is important for sawmills, he explains. The pellet industry also provides economic opportunities and employment, contributes to fossil fuel substitution and helps manage fire and wildfire risk.

“As an industry, we want to be responsible using the low-end, what’s left behind material, that no other industry can use,” Murray says. “And if by doing that we can create a renewable product, lower greenhouse gas emissions and offset the use of fossil fuels by replacing coal, for example, then we think we’re being an environmentally responsible sector.”

Gary Bull, forestry professor and one of the study’s lead authors, explains that one of the study’s surprising findings was the amount of dead biomass in the forest that accumulates due to natural disasters such as fire and insect disease. “While you leave some on the ground for biodiversity reasons … there is still this huge surplus of biomass on the landscape, and if you don’t find an industrial way to use it and generate economic activity, the current regulations force you to burn it on-site and create a lot of emissions,” Bull says. “So, these emissions are a huge problem from a societal point of view in terms of dealing with the climate change problem.”

The researchers did three case studies throughout the province, Bull explains. One plant was a Drax facility located near Burns Lake, which has a community forest partially owned by First Nations communities that receive a share in the revenue from harvesting the forest. “The community had no option to try and get that wood or forest residue to a pulp mill. It’s just too far away, so the economics don’t work,” he explains. “So, the community was very supportive of installing a pellet plant.” The second case study was a smaller operation—Skeena Bioenergy near Terrace, British Columbia, where the study found that First Nations communities worked with the sawmills to dispose of residues in the remote location. The third case study was of Drax Meadowbank, a larger facility.

Utilization of sustainable biomass provides remote and indigenous communities with a way to decarbonize, Bull explains. “Frankly, I’ve been in conversations with several indigenous communities that want more, rather than less, use of pellets or chips—biomass used—because in remote communities, they’re most interested in getting off diesel. Biomass is the most logical way for them to get off diesel power plants in these northern remote communities,” he says. One challenge he believes the pellet industry must work through is engaging civil society, especially indigenous people, in conversations about complex problems. “I’m particularly concerned about the role of indigenous people and how that plays into their land ethic,” Bull says.

Murray believes the main takeaway from this study is that the wood pellet industry is responsible and concerned about forest health, ensuring complete utilization by turning previously difficult-to-get-rid-of forest and mill residues into a renewable energy product that helps lower GHG emissions around the world. “All in all, I think [for] the pellet industry, it’s a good news story,” he adds. “By doing this study, we’ve had third parties verify that we’re sourcing responsibly.”

Author: Katie Schroeder

Staff Writer, Pellet Mill Magazine

kschroeder@bbiinternational.com

Advertisement

Advertisement

Upcoming Events