Baltic Boom

PHOTO: AS Graanul Invest

January 22, 2016

BY Katie Fletcher

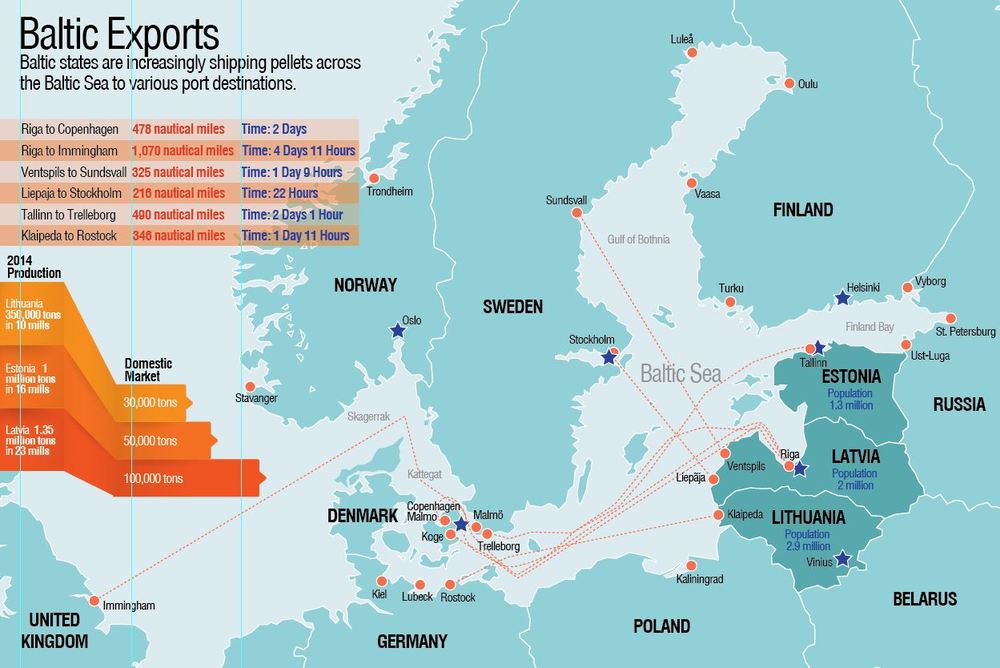

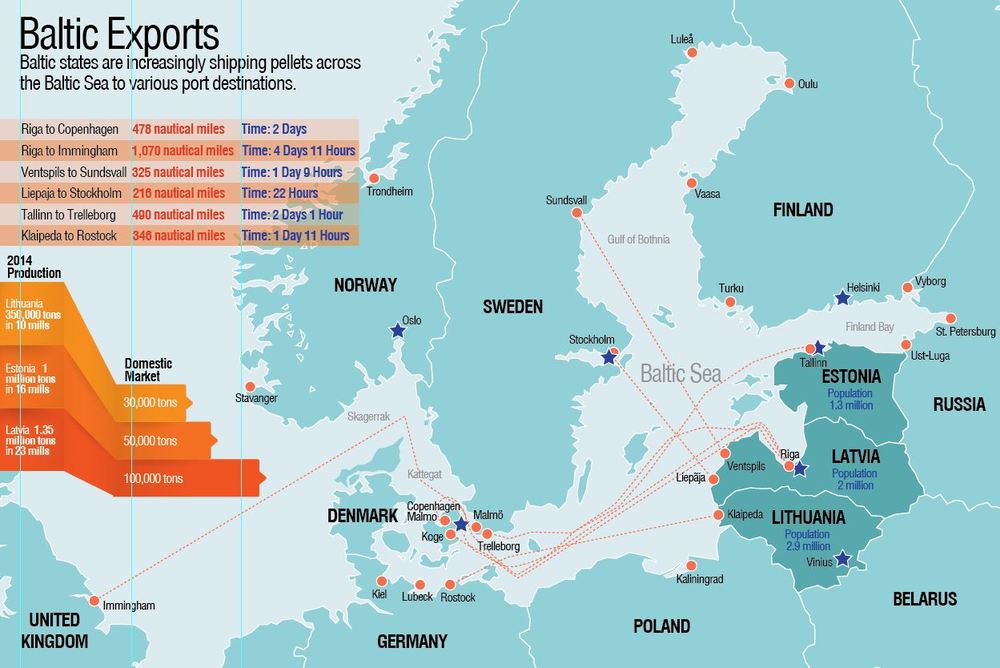

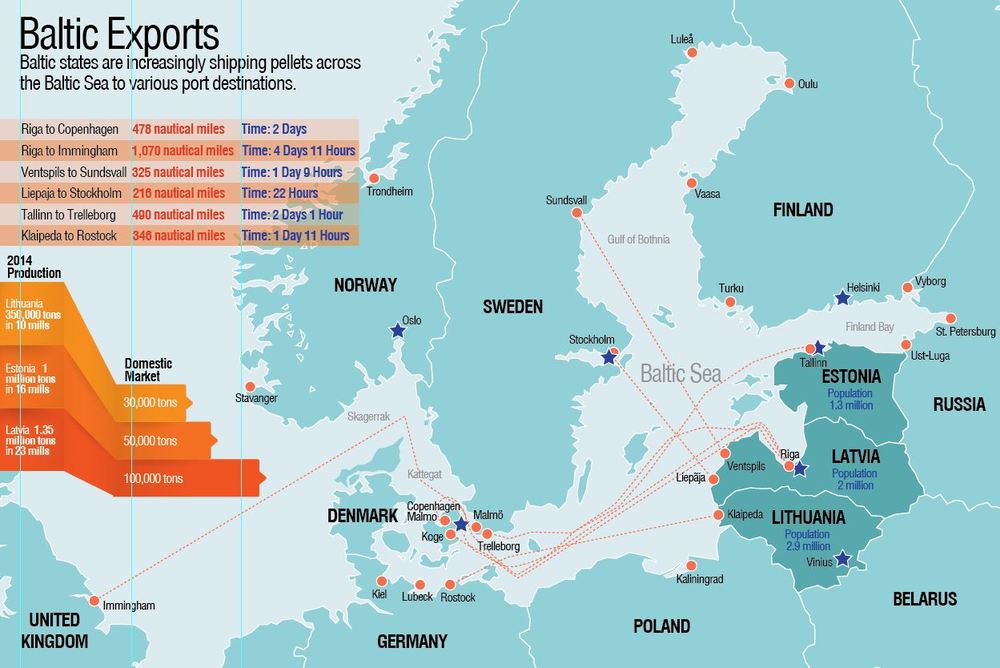

On the Eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania have remained almost unrecognized players in the wood pellet export market compared to large exporters like the U.S., Canada and Russia. Even so, Latvia, though drastically smaller in size, has become the leading exporter in the European Union and neighboring Estonia is 2014’s fourth largest. Much of Lithuania’s land is dedicated to agriculture, but even so, the country has been increasing its exports, distributing roughly 300,000 tons in 2014. Thirty-five percent of aggregate EU28 exports in 2014 came from the Baltic states—20 percent from Latvia, 10 percent Estonia and 5 percent Lithuania. Globally, 27.1 million metric tons of pellets were produced in 2014, about half, or 13.5 million, produced in the EU. Total production in the Baltic states amounted to 2.65 million tons in 2014, much of which was exported. Russia and the Baltic states combined produced 4.15 million tons of wood pellets during 2014. Producers in countries like the Baltics and Russia can more easily distribute their production to serve local European markets as opposed to oversea producers. Russian and Baltic pellet competition was discussed at the 2015 Wood Pellet Association of Canada conference in Halifax, Nova Scotia. “Those are the guys you are really competing with, because a vast majority of what is consumed in Europe is consumed locally,” says Arnold Dale, vice president of the bioenergy division with Ekman Group, addressing mainly North American producers at the conference.

With new mills in the pipeline, the Baltic states, increased presence in the European pellet industry may place this region on the radar as significant pellet producers and exporters, especially to serve local heating markets. “The outlook is quite optimistic with several new plants currently under construction in Latvia, which will add another 350,000 metric tons of production,” Dale says. “In Estonia, there are also a couple of projects, which will add 150,000 metric tons, and in Lithuania an expansion project at one of the existing producers will add 30,000 metric tons.”

Abundant forest land, relatively low costs of production, port accessibility, low energy costs and low taxes make conditions for pellet production quite favorable in the Baltic states. As for consumption, the domestic wood pellet market remains relatively small and mostly serviced by local small producers. One reason for this is Baltic cities have district heating systems and the biomass used for heat is largely inexpensive wood chips. Wood chips are also used for combined-heat-and-power (CHP) plants.

Latvia Takes Lead

Pellet production in the Baltics started in the late ‘90s when Swedish company SBE decided to invest in a wood pellet mill in Latvia, according to Dale with Ekman Group. SBE Latvia Ltd. is still Swedish-owned and is now part of Agroenergi Neova Pellets AB Group. Dale says the total production of this group is about 600,000 metric tons annually.

The wood pellet industry in Latvia evolved out of the sawmilling industry, and has grown rapidly over the past 10 years. Another leading wood pellet producer in the Baltic countries—currently the largest in the EU—is AS Graanul Invest. “I think there are two sets of investors in this business, one group has invested in one mill and runs it (often connected to sawmills) and the second group is independent producers who see that as a principal business line,” says Raul Kirjanen, Graanul Invest CEO.

The stepping stone that helped Graanul gain largest producer status in the EU was the acquisition of Latvia-based producer SIA Latgran in July. Latgran was the largest pellet producer in Latvia with four mills reaching an estimated 600,000 tons of pellet production in 2015. Graanul Invest now operates 11 pellet plants in total—four in Estonia, six in Latvia and one in Lithuania. Kirjanen estimates the company will produce 2.15 million metric tons of wood pellets in 2016. As the acquisition of Latgran took place mid-2015, Kirjanen says the company’s production for the year is around 1.6 million metric tons, 99 percent of which was exported. “Acquisition of Latgran gives us a lot of synergies in logistics, sales and procurement,” he says. “We will also be able to enter into bigger and longer-term agreements with our combined volume.”

AS Graanul has four CHP plants today and a fifth should be finalized in the second quarter of 2016. All of them are in the company’s existing pellet mills. “We use forest chips as fuel and generate heat and electricity for our pellet plants,” Kirjanen says. “In my opinion, it is very important that the greenhouse gas footprint of pellet production is minimized and CHP technology based on local biomass is the best way to achieve this.”

Following its acquisition of Latgran, AS Graanul Invest plans to continue to grow. Kirjanen says in 2016 the company will build one more mill in Latvia—250,000 metric tons per year—and is expanding two existing mills. He adds that the company is looking internationally, but it is still too early to disclose details.

Advertisement

Joining SBE and Graanul Invest, Newfuels is another large producer in Latvia. Altogether, Latvia is home to 23 mills, making it the main Baltic producer, which produced 1.35 million tons of mostly industrial grade pellets last year. Production was largely exported to Denmark (500,000 metric tons) and the U.K. (600,000 metric tons), while the remaining pellets were distributed in Sweden, Italy and others. Latvia produces about 550,000 tons of premium pellets annually, approximately 40 percent of total production, which varies annually. Because a vast majority of Latvia’s production is exported, its domestic market remains relatively small, around 100,000 metric tons. Besides its pellets, significant amounts of transit move through Latvia—estimated at up to 80 percent. The country’s largest ports include Riga, Ventspils and Liepaja. Graanul Invest’s main export port is Riga. Oil, oil products and coal account for more than 60 percent of seashore transportation.

Feedstock to make pellets across the Baltic region mainly comes from two sources. Graanul Invest gets approximately 50 percent of its feedstock from the sawmill industry residues and 50 percent from low-quality roundwood, which varies amongst Graanul’s plants. These two sources are used for pellet production feedstock across the Baltics. Forest growth used as pellet production comes from coniferous softwood mainly pine and spruce with small amounts of alder, aspen and birch also used. In Latvia, 38 percent comes from spruce, followed by 29 percent from birch and 19 percent pine. According to Dale, Latvia has an abundance of natural forest growth. Over the past 14 years, the amount of standing wood in the forests of Latvia has increased by approximately 125 million cubic meters or 23 percent. In fact, forest resources are growing faster than demand for wood to create energy—in the Baltic Sea region every year by over 140 million cubic meters (fellings vs. increment). Approximately 60 percent of Latvia is covered in forest growth with a population of only about 2 million people, according to Didzis Palejs, a member of the board and one of the founders of the Latvian Biomass Association or LATbio.

Pellet prices in Latvia fluctuate from producer to producer, but Palejs estimates the average sales price for bagged pellets—15-kilogram bags of premium class ENplus A1 certified pellets—is around 130 or 140 euros ($141 to $152) per ton ex works (named place of delivery, placing the maximum obligation on the buyer and minimum obligations on the seller). Dale says for the residential market, the average price of ENplus A1 pellets in the Baltic states is 150 euros ex works. Industrial pellets average around 115 to 124 euros per metric ton free on board prices in Latvia, depending on the producer and contract.

Two interesting developments Palejs draws attention to when discussing current and upcoming developments in the Latvian pellet industry are the location of new pellet mills and changes in the logistical chains due to the Russian embargo. He says one of the latest tendencies is to build new mills deeper inland, more than 100 kilometers from the harbors, making these mills more competitive to consider roundwood for raw material. Due to the lack of local consumption for low-grade roundwood, the possibility of future pellet production creating a demand for the product could help the woodworking industry stay competitive, according to Palejs.

Another change Palejs is seeing is in the logistical chains due to the Russian aggression in the Ukraine and the Russian sanctions against Europe and other countries locally. He says transport westward from the Baltics is getting more expensive, because the Russian sanctions have decreased the flow of cargo toward Russia. “It’s hard to get the transportation of pellets by truck to Western Europe, because it’s hard to get trucks to pay higher prices,” Palejs says. “Because of this, pellet producers are looking at changing their logistical chains. They are now using container transportation, meaning they export their goods by the container or in bulk overseas.”

Estonian and Lithuanian Industries

Estonia and Lithuania have smaller pellet production capacities than Latvia, but the industries are comparable in many ways. Pellet business began in Estonia a little less than 20 years ago, evolving out of the animal feed industry. The markets at that time were Sweden and Denmark. Estonia had limited pellet production until a few years ago and has grown rapidly since, producing 1 million tons in 16 mills in 2014. According to Kirjanen, Estonian production is growing at the pace of 300,000 tons per year, but he thinks it will reach its available raw material limit at around 2 million tons per year. In addition to Graanul Invest, Estonia has two big producers at 100,000 metric tons or more, Stora Enso and Purutuli. Like Latvia, Estonia’s domestic market is small in comparison to its exports, at an estimated 50,000 metric tons. The country’s main export markets are Sweden, Denmark, Italy and the U.K. Kirjanen believes around 30 percent of the pellets produced are premium and 70 percent industrial.

Over half of Estonia’s imports and exports are transported by sea, nearly 70 percent of sea freight is transit, and in the Port of Tallinn it reaches up to 76 percent. The country’s largest ports include Tallinn—primarily oil and oil products—and Sillamae, an all-purpose port and the most eastern EU port. Although most of Graanul Invest’s production is exported through Latvia’s Riga port, the company also uses the Port of Tallinn and Port of Pärnu in Estonia.

Further south, Lithuania is the smallest producer of the three producing roughly 350,000 metric tons in 10 mills during 2014, due, in part, to the country’s more favorable conditions for farming. Much of Lithuania’s production is premium-quality bagged and delivered by truck predominantly to Italy, Germany and Denmark. Lithuania’s ports deal with large amounts of transit—42 percent—much of which comes from Belarus. The largest ports in the country include the all-purpose Port of Klaipeda and Butinge port. Following the trend of the other Baltic countries, the Lithuanian domestic market is small, estimated around 30,000 to 50,000 metric tons per year.

Advertisement

Domestically, Lithuania uses around 10 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity and 20 TWh of heat. “Heat is the most important energy source for Lithuania,” says Remigijus Lapinskas, current member of the board and previous president of the Lithuanian Biomass Energy Association or Litbioma. “Biomass is the best, local and renewable resource for addressing the demand for heat.”

The biomass used for heat is mostly used in the form of wood chips, however, not pellets. Wood chips are the cheapest biomass for Lithuania’s district heating systems. Litbioma estimates that this year biomass will overcome the market share of gas in district heating at 55 percent. In the next few years, Lapinskas says they estimate only 20 percent or a maximum of 30 percent of district heat will be produced with gas. Currently, biomass plays a minor role in the production of electricity, but it’s anticipated 15 to 20 percent of electricity will be produced from biomass in the coming years, up from its current 2 percent.

Baltic Roundup

Overall, producers within the Baltic states generally run mills in the 70,000 to 90,000 range with a couple that produce around 200,000 metric tons annually. According to Dale, there are also quite a few tiny producers that are typically attached to a sawmill and produce less than 10,000 tons per year. Pellet quality and certifications have also become widespread amongst producers. Organizations like LATbio and Litbioma have programs helping these certifications move forward. Most, if not all, of the producers who export residential quality wood pellets have become ENplus certified, and there are 27 ENplus producers in the Baltics—10 in Latvia, nine in Lithuania and eight in Estonia.

Producers like Graanul Invest have also looked at the sustainable biomass partnership (SBP) certification framework in addition to their Forest Stewardship Council and Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification schemes. “Our customers are interested in this certification and, of course, we are looking at it,” Kirjanen says. “However, the way the certification is built up makes it very difficult for us to use it. It is very easy to use if we would use roundwood instead of residues, but for me this seems to be the least sustainable solution.”

He adds that wood pellet production initially started in Scandinavia as a way to utilize and give value to the residues and low-quality wood that is not needed for any other industry. “If we now need to move away from residues to use logs because that is needed for certification purposes, then the certification scheme does not make any sense, as I see it,” Kirjanen says. “It seems to me that they have realized it themselves as well, and hopefully there will be a solution to the problem.” Kirjanen mentioned the upcoming Dutch system as a reasonable approach where residues are exempt from certification and roundwood has to be certified.

According to LATbio, within 10 years the Baltic Sea region is expecting large increases of biomass consumption, more than 25 million tons. However, further growth depends on policy development and weather condition dynamics. There are few, if any, incentives in the Baltics for biomass, especially pellets, which doesn’t help the already low local pellet consumption. According to Dale, there is a reduction in value-added tax for private households using biomass, instead of 22 percent, consumers pay 10 percent. In Latvia, Palejs says there are feed-in tariffs for electricity, but they are rather limited. Palejs believes if people are wealthy enough, they’ll make the investment to switch from firewood to pellets. LATbio estimates Latvian biomass consumption in 10 years could be 6 million tons per year of wood chips for district heat and CHP and 3 million tons per year of pellets for residential installations. Likewise, increases are expected in Lithuania and Estonia, with LATbio estimating over 5 million tons of wood chips and 4 million tons of pellets consumed each year, and over 5 million tons per year of wood chips and 2 million tons of pellets annually in Estonia.

As for nearby Russia, Dale says the country does not impact Baltic pellet producers in a major way. “Some sawmills import logs from Russia, but this is a very limited supply,” he says. Dale does share that “Byelorussian production is increasing rapidly and several Latvian and Lithuanian pellet producers are currently constructing wood pellet plants in Byelorussia.” He says that this year, Byelorussian pellet exports to the EU will be around 125,000 metric tons, and once the new mills are operational, this figure will more than double to over 300,000 metric tons.

The European wood pellet market is the world’s largest market and Dale doesn’t foresee that changing. Although Europe is still the world’s largest wood pellet producer, with 50 percent of global production, Dale says North America may overtake Europe in time. In addition to the Baltic states, production volumes in nearly all European countries are showing healthy increases. Dale says that consumption in the power market has leveled off. “It looks like 2016 will be a tough year for industrial pellet producers,” he says. Consumption in the CHP and heat markets are showing good growth, however, and more wood pellet manufacturers are selling into heat and power markets.

The Baltic states, led by Latvia, are on track to continue the boom they set off in these markets, utilizing the region’s abundant raw material and port accessibility. “It has been growing very rapidly—especially within the last 10 years,” Palejs says. “Before, it was a minor industry, but then when the pellet industry in Western and Central Europe was starting to develop, the demand for pellets was rising, and we already had the experience in pellet production in the industry.”

Author: Katie Fletcher

Associate Editor, Pellet Mill Magazine

701-738-4920

kfletcher@bbiinternational.com

Upcoming Events