Betting on Biomass

SOURCE: BIOMASS ENERGY CENTRE

September 20, 2011

BY Peter Taberner

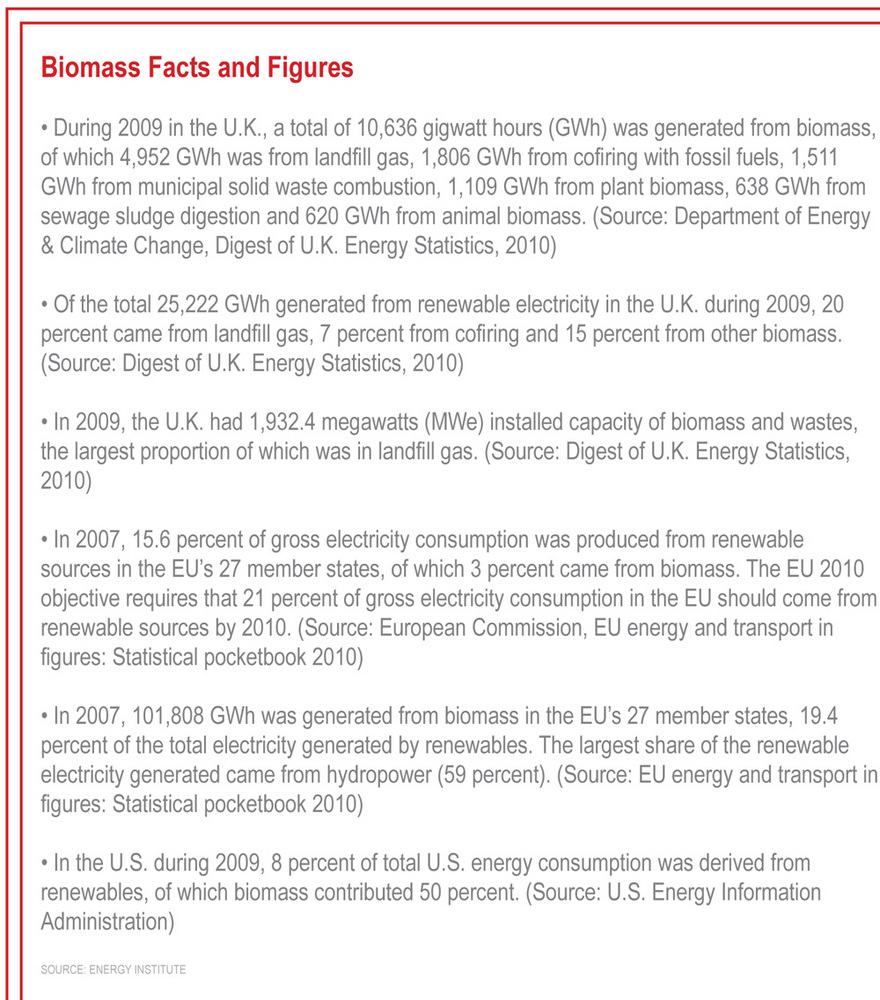

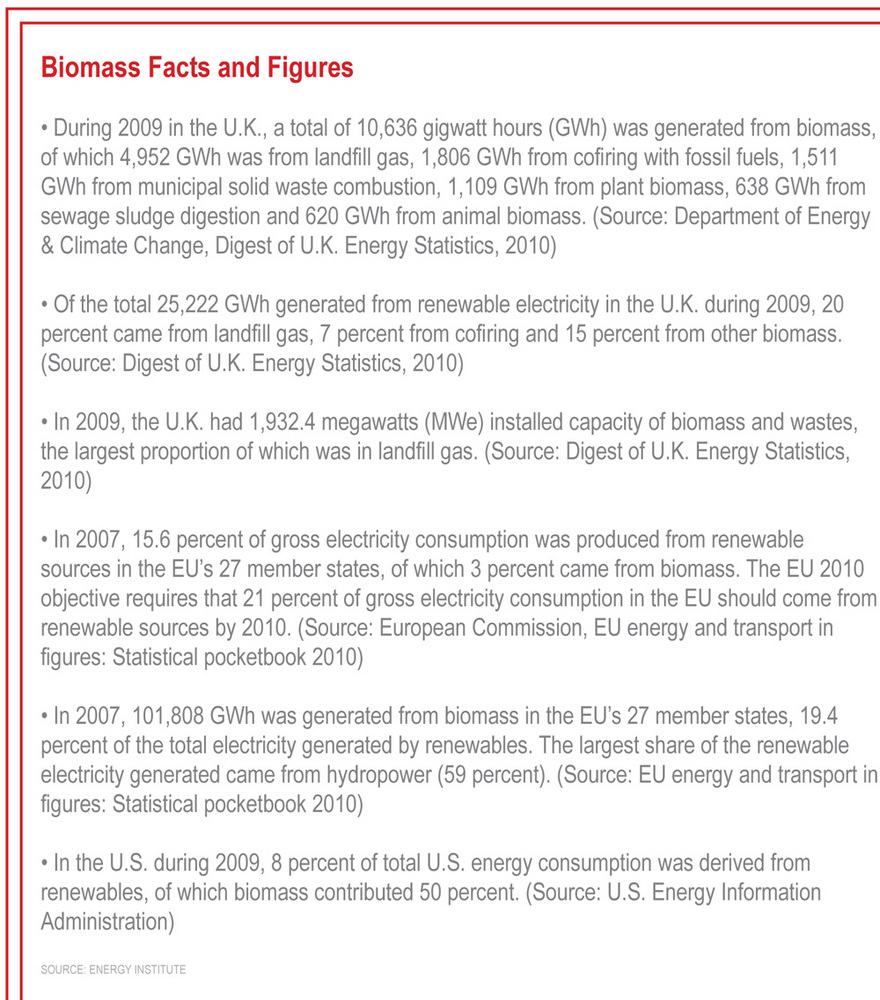

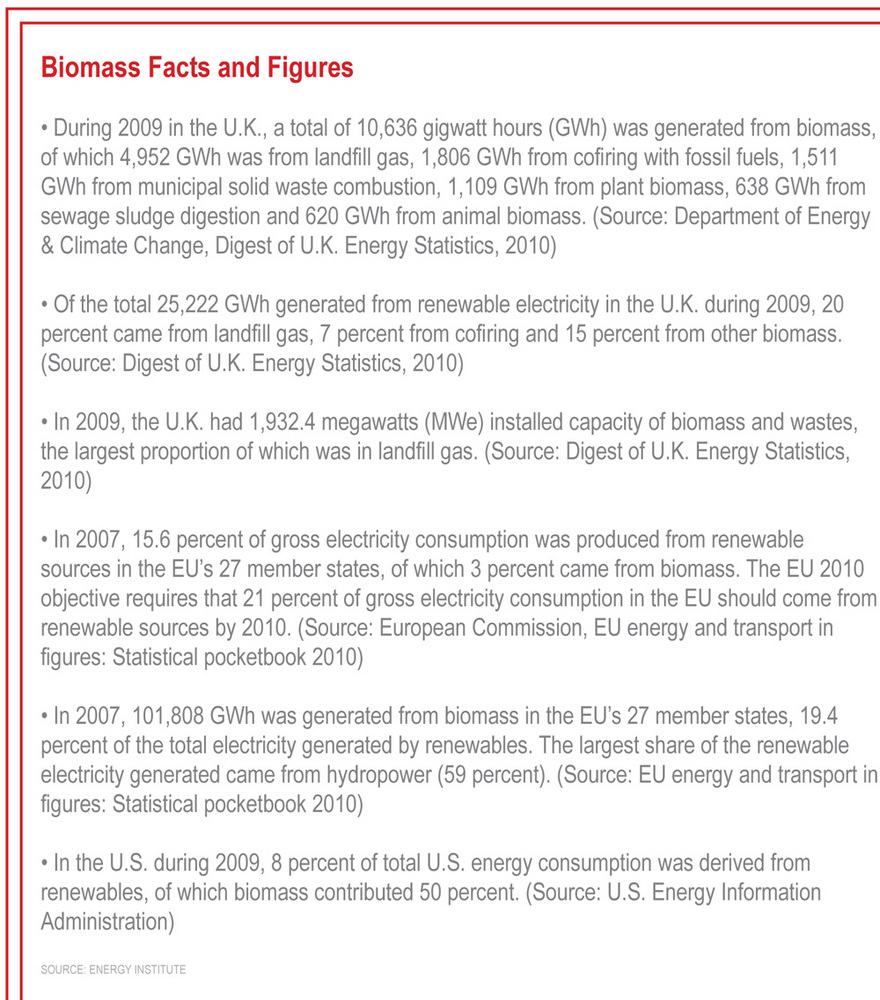

The U.K., along with all members of the European Union, is evolving its energy base to meet the ambitious target of 20 percent of fuel originating from renewable sources by 2020. The Conservative-Liberal coalition government believes that the biomass market is worth taking a bet on.

New biomass plants could be sprouting up all over the U.K. with planned developments from Forth Energy’s projects in Scotland in Dundee, Leith and Grangemouth, to Peel Energy’s plant in Manchester, all the way down to the southern coast with Helius Energy’s wood fuel plant in Southampton.

Incentivizing Biomass

Despite endorsing more severe spending cuts compared to other comparable economies, the coalition government has supported the biomass market with generous subsidies, mainly because of the cost of biomass in relation to other renewable energy sources.

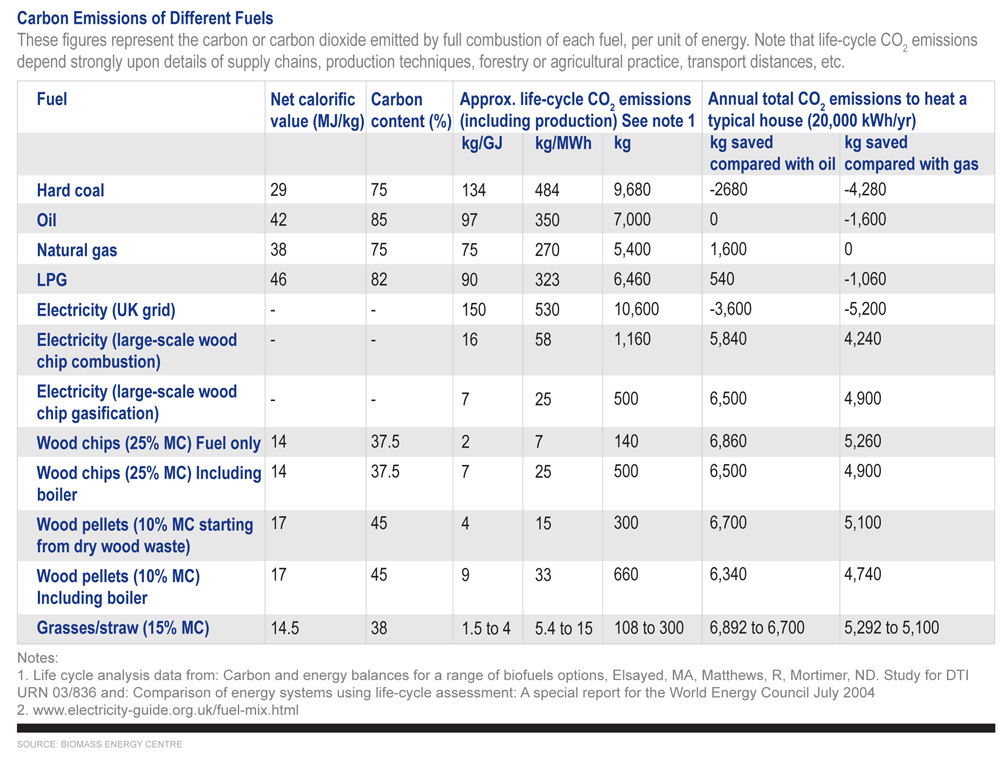

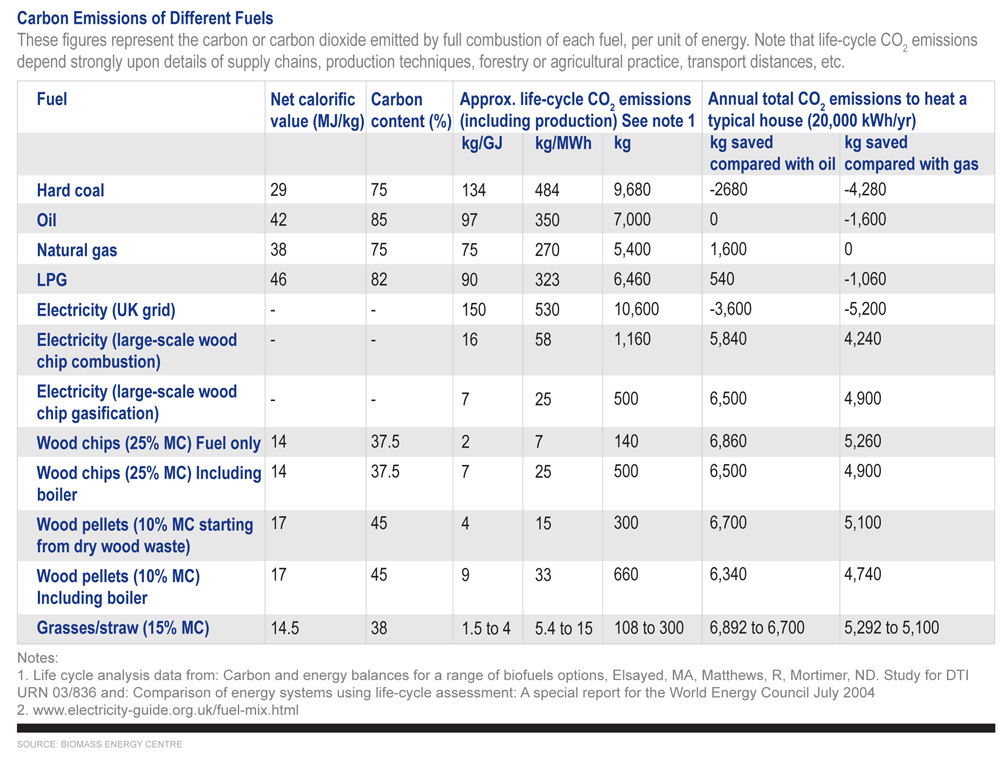

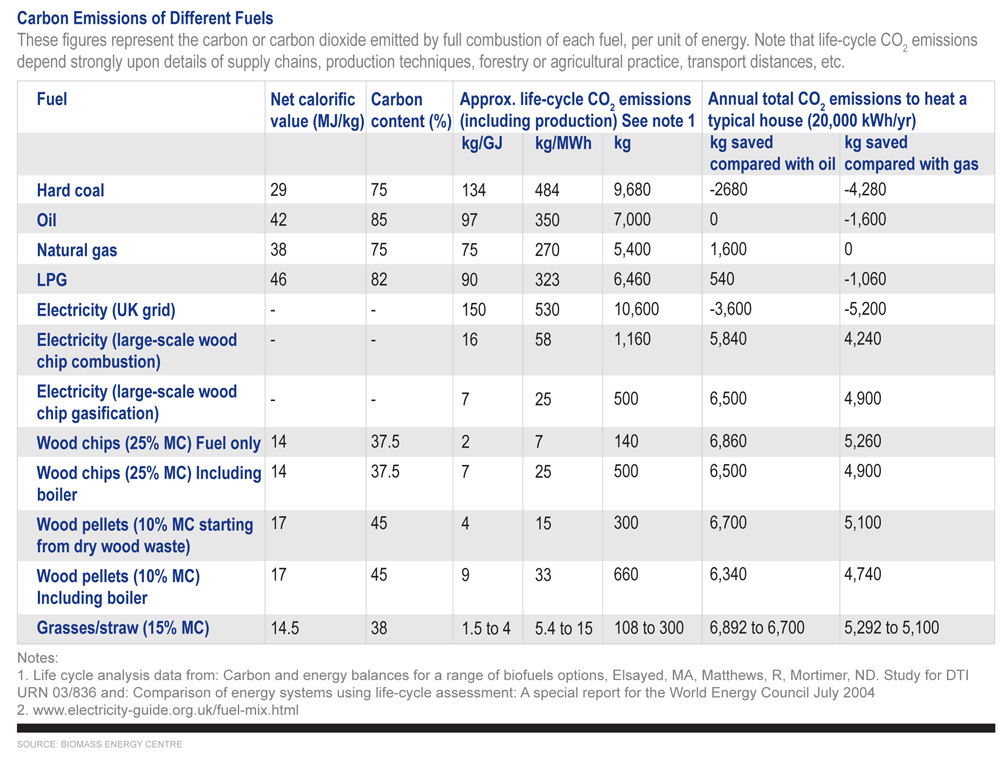

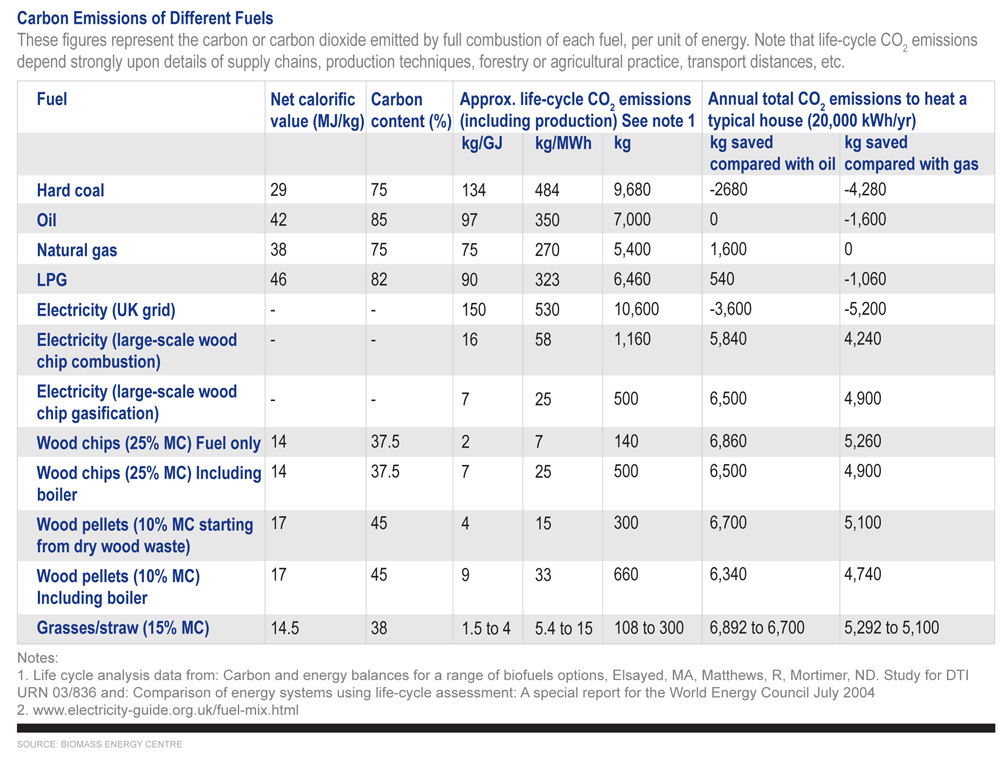

“Biomass heat is the lowest-cost renewable in terms of the [metric tons] of CO2 saved per pound invested, usually by some margin,” says Jim Birse, commercial director of Econergy Ltd., a U.K.-based provider of biomass solutions. “The Renewable Heat Initiative, that will provide financial assistance to the generators of renewable energy including long-term tariff support to big heat users, will cost a lot less per metric ton of CO2 than the feed-in tariffs for PV (photovoltaic).”

“Heating and heating fuels account for 45 percent of the U.K.'s CO2 emissions, and heating accounts for 70 percent plus of a typical home's energy use—any energy policy aiming to reduce CO2 must tackle this sector,” Birse says. “Biomass boilers are directly compatible with standard heating and hot water systems, and can be used to raise MPHW (medium pressure hot water) and steam for industry applications.”

An official report produced for the Department for Energy and Climate Change by AEA, a provider of analysis, advice and data on economically sustainable solutions for energy and environmental issues, concludes that U.K. feedstocks are projected to provide one-third of bioenergy by 2020, producing about 1,800 petajoules of bioenergy supply, equivalent to 20 percent of current primary energy demand in the U.K.

There will be exponential increases in imports, however, as the forecast is for the proliferation of energy crops being planted globally. The EU, Eurasia and non-EU countries could provide 70 percent of potential imports by 2030, and there remains the juicier prospect of China becoming a big export market if it also increases its crop. This is also why many of the U.K.’s new biomass plants are being built in coastal areas in ports.

Feedstock Supplies

Advertisement

Even though a reliance on import markets has been anticipated, the U.K. still possesses a substantial market supply of its own. Wood waste fuels that are being consumed for combined-heat-and-power (CHP) boilers are increasingly being used by local authorities in residential and industrial properties. That is despite the much remarked upon initial steep outlay for biomass boilers, which are priced at about £11,000 ($18,000) compared to £4,800 for installing solar power.

Agricultural waste including dry residues from straw, corn stover and poultry litter can be burned by medium-scale biomass power plants and CHP sectors to produce between 10 and 50 megawatts of electricity.

Food waste is also there for the taking, with huge amounts of organic waste material being created from manufactured foods and drinks, including beer, whiskey and wine, and cheese. It has been estimated that 92 percent of brewing ingredients end up as waste, mostly spent grains, and that dairy products produce 40 million cubic meters annually, mainly for cleaning, which produces effluent containing high levels of organic residues.

Additionally, energy crop growth has potential, and projections may ensure plans are made for increased planting. For example, 700,000 hectares (1.7 million acres) is 3.7 percent of U.K. agricultural land and is the area that used to be “set-aside” under EU agricultural policy. “If this area were to be planted with woody energy crops, we'd expect an annual yield of something like 9 million tonnes (9.9 million tons) per year,” Birse says.

“The U.K. possesses considerable untapped biomass resources,” says Keiran Allen, technology acceleration manager at the Carbon Trust. “Up to 4 million tonnes exists in under-managed private forestry alone, and the Forestry Commission estimates that up to 2 million tonnes could be sustainably extracted in England for fuel use every year. Beyond this, large volumes of waste wood are still currently going into landfills and between 3 million and 5 million tonnes per annum could instead be used for fuel. Marginal land could also be used for energy crop planting.”

“In the U.K. we are starting from a low base with lower levels of affinity with biomass and wood as a fuel,” Allen says. “We also face lower absolute availability of materials relative to our total annual heat demand and there is a shortage of forestry-specific skills which must be developed to enable the industry to grow.”

Other constraints may be affected by finance and confidence in the supply chain, and for markets to become successful may depend on the regulatory framework that any nation implements. As the report produced for the DECC states, there is extensive room to grow energy crops in the international marketplace including in the U.K.

Opposing Forces

Advertisement

While biomass may be a much-vaunted renewable energy source in certain quarters, it is not without its detractors, who question the carbon neutrality of burning wood plus the aftereffects of any deforestation, and whether this will outweigh the emission savings in the long run. Taking into account capital and largely populated cities, whether more greenhouse gases released in the air is appropriate is dubious.

This view is supported by Biofuel Watch, which keeps an eye on the negatives of bioenergy. “I suspect that they are concerned about 'keeping the lights on' when nuclear plants are due to be decommisioned combined with public fears about safety; then there are concerns about energy security from Middle Eastern oil and Russian gas,” says a spokesperson for the organization. “The negative effects of biomass in comparison to other renewable energies are numerous and include rainforest destruction and other habitat loss leading to a reduction in biodiversity, land evictions and other human rights abuses, water and soil degradation, genetically engineered plantations with increased fire risk and water use, loss of carbon sinks, food sovereignty and food security issues and lastly but by no means least, air pollution and black soot.”

The debate about biomass rages in the U.K. as the prospect of reliance on it increases, however the watchdog’s view is forcefully dismissed by Geoff Hogan of the government-funded Biomass Energy Centre.

“There are all sorts of rubbish published about the carbon impact of biomass, often along the lines of ‘cutting down trees to burn is bad,’” Hogan says. “If managed properly biomass for fuel is sourced as a byproduct of existing good forestry practice and is poor quality material removed as a part of thinning operations and trimming of side branches, slab wood, chips and sawdust from the processing of the high-quality timber in sawmills for use in construction and joinery. Trees are essentially grown for timber; biomass for fuel is a byproduct of the industry.”

“However, it can also be done unsustainably and inappropriately giving unacceptable direct and indirect land-use impacts, poor carbon savings and negative social impacts,” he adds. “Legally harvested timber in the U.K. is subject to the U.K. Forestry Standard, imposed via felling licenses and is therefore sustainably sourced. Illegally obtained wood in any country is unlikely to be sustainable.”

Advocates of biomass should also be wary of ‘not in my backyard’ groups—or as the colloquial term would have it NIMBYs—who are against biomass construction. This has erupted more conspicuously against Helius Energy’s plans for a 100-megawatt wood fuel plant in Southampton, even though they announced they would not source fuel from protected areas in an attempt to bat off local protests.

Vociferous opposition from local residents criticized the £300 million building, which included a 100-meter-long chimney stack, in the docks area of the city as an eyesore and possessing no positive environmental impact.

Developers are now being forced into retreat by the protests with a delay on fresh consultations for the plants’ designs to extend community consultation, and this comes after it was announced that the original designs are being downsized.

The significance of this should not be dismissed when taking wind energy into account. There is thought to be more than 230 localized campaigns against wind energy, and they have campaigned to great effect as existing council laws defer to the concerns of local residents’ priority over turbine building. As a result, approval rates for turbines have dropped by 50 percent, say Renewables Energy U.K., who believe local developers are alarmed at the consistency of negative decision making on wind farm building. According to figures from law firm McGrigors LLP, who have six offices across the U.K., 48 percent of onshore farms are being refused planning permission.

Alison Jones, community relations manager of the U.K. and Ireland development at the RES Group, who have a biomass project in the planning stage in North Blyth, and about to begin the pre-planning public consultation on an Alexandra Dock project in Liverpool says “RES is experienced in renewable energy project development and we take community consultation seriously. A comprehensive process of consultation that engages with local people and stakeholders from an early stage allows an informed debate to take place. This helps us to identify issues of concern, negotiate solutions and design a low-impact project that will be welcomed as a positive asset by the local community.”

The coalition government and developers will be hoping that progressive steps such as these will work—making that bet worth taking after all.

Author: Peter Taberner

Freelance Writer

tabernerp@yahoo.co.uk

Upcoming Events