Enabling Efficient Exports

January 30, 2013

BY Anna Simet

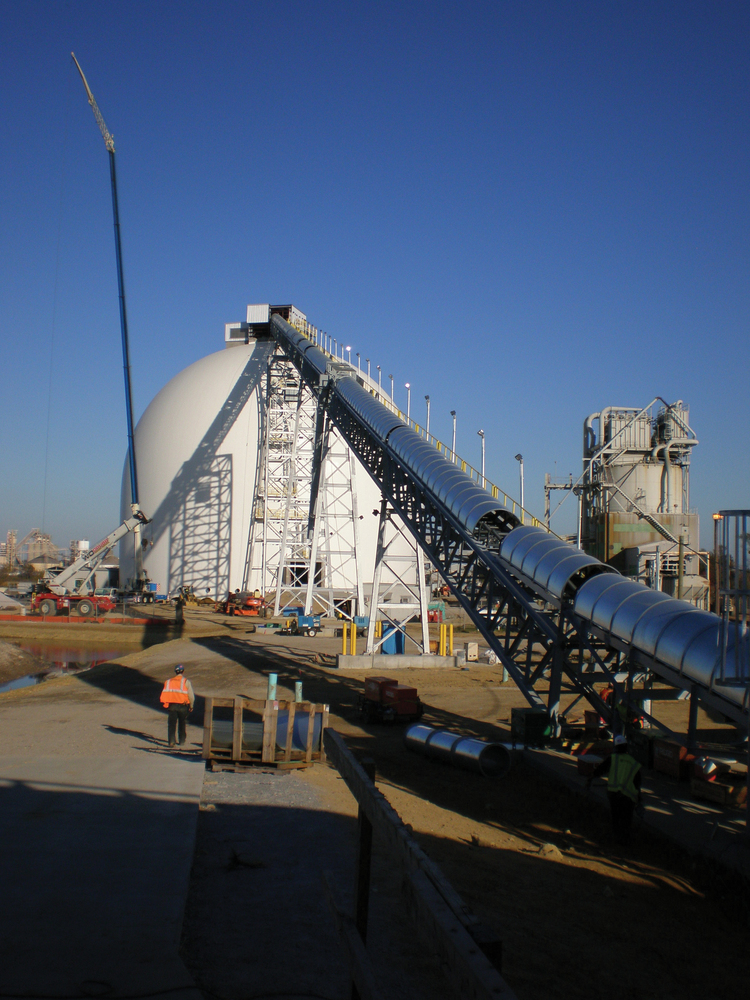

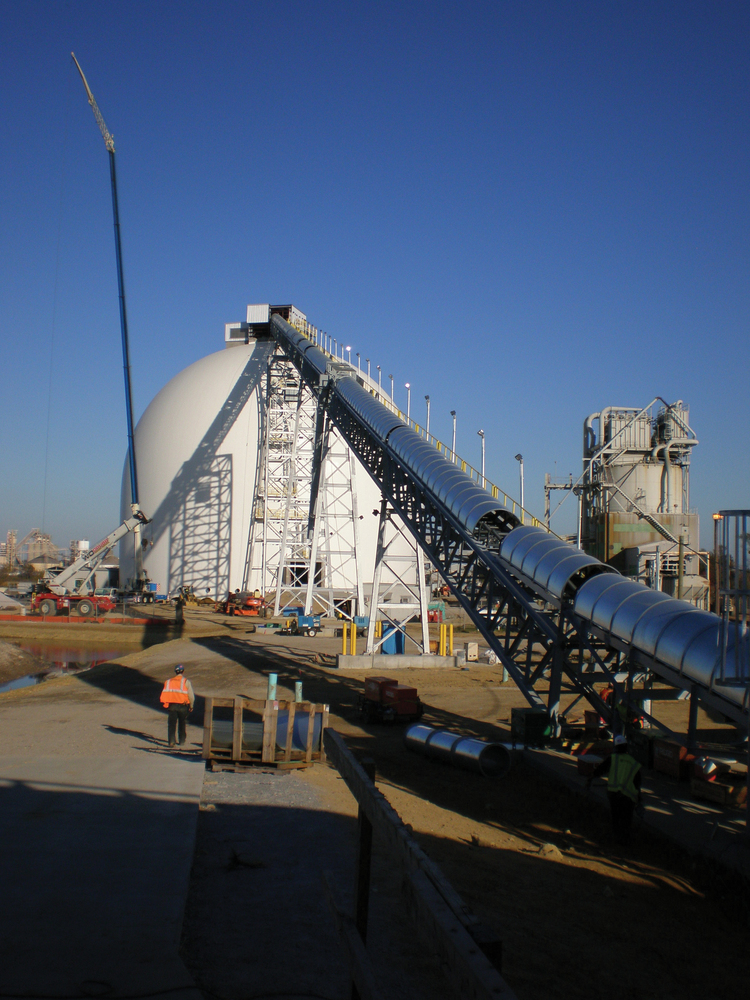

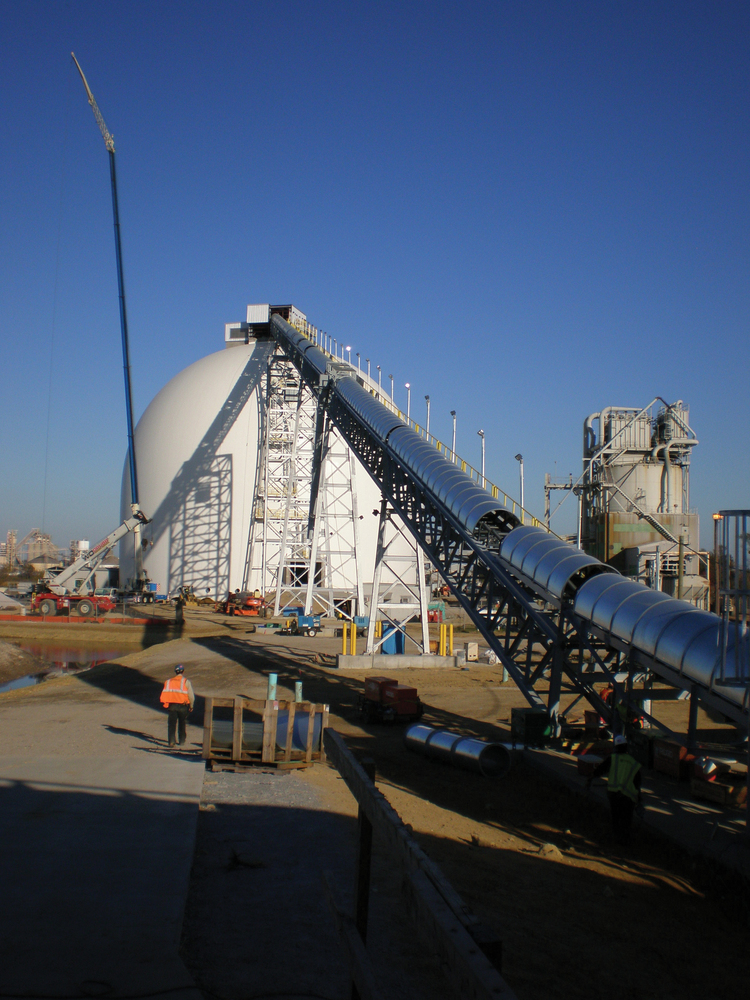

At the Port of Chesapeake near Norfolk, Va., Enviva LP owns a deep water terminal that serves as the company’s shipment point for its Mid-Atlantic pellet plants. Rising high above most structures at the site is a central component of the pellet export infrastructure there—a gleaming white, 175-foot tall storage dome, which will soon be accompanied by a twin.

Able to withstand hurricane winds of above 300 miles per hour and earthquakes exceeding 8 on the Richter scale, such domes are becoming the storage method of choice at pellet export operations, and not simply for their natural-disaster-resistant qualities. In fact, a soon-to-be-revived cargo port at the Virginia Port Authority’s Portsmouth Marine Terminal will host two of the same storage domes that Enviva utilizes, a project that the VPA has contracted ecoFuels Pellet Storage LLC, which is a joint venture between Capital Management International and energy infrastructure developer multiFuels LP, to take on.

The joint venture has a 20-year lease on a 15-acre site that includes construction of the pellet storage domes, which will have a combined storage capacity of about 1.2 million tons. Although there are no immediate plans for construction of a nearby pellet plant for supply—which at first thought may seem like a backward plan—Peter O’Keefe, ecoFuels partner, says that when it comes to pellet exports, storage facilities are key. “You have to be able to efficiently store them,” he says. “We have found that storage needs to be addressed first and foremost, and then plans (supply) can be built out from there. In the U.S., we are really blessed with great ports and storage potential; in Canada, that’s a big challenge.”

The Portsmouth Terminal is a much-sought after, short haul to Europe—thus boasting great export economics—and it’s very close to a wood basket. Not only that, but, according to O’Keefe, in rural parts of western Virginia and North Carolina there is tremendous rail access, a recipe that may make it viable for smaller producers to get a foot in the export door. So rather than using the port to export solely its own supply, O’Keefe says, ecoFuels will also bring in third-party supply.

Another bonus is the port’s ability to accept any size ship, and exporting pellets from there to Asia within the next few years is a possibility, according to O’Keefe. For now though, getting the right infrastructure in place is the main focal point, and that begins with construction of the domes, which will be built by Idaho-based Dome Technology.

Superior Storage

In 1975, Idaho brothers Barry, David and Randy South began experimenting with inflatable airforms, the end result of which was their first patent, achieved in 1980. In a nutshell, an impermeable and tough fabric is attached to a solid, ring beam foundation to form a freestanding structure with no supports on the inside. Once the structure is inflated, the inside is sprayed with polyurethane foam to harden it and also provide an insulation layer. A rebar framework is then built and filled with shotcrete, a type of concrete that is projected through a hose via a high-pressure system, to hold the steel infrastructure in place. After that, crews follow the construction plan according to what the buyer wants, which in the case of pellet storage may be tunnels dug beneath the ground floor for conveyor systems that will transport the pellets to ships, and an aeration system.

Advertisement

So what really makes these domes ideal? Lane Roberts of Dome Technology says that out of the three ways to store pellets—flat warehouse, silos or domes—domes require the least amount of real estate, somewhere around three times less the amount of space that a flat warehouse would require. That’s a money saver, as is the domes’ rigidity. “Typically ports don’t have great soil—a lot is filler from years ago and not stable like it would be inland—so flat storage and silos need deep foundations, which is a significant cost to the project,” Roberts says. “Domes are very rigid and hold their shape, so we can often eliminate deep foundations, and depending on the size of the storage, that can save millions of dollars.”

Since the bulk of the work is done inside of the domes, inclement weather doesn’t typically hinder construction plans, Roberts points out, and because of their waterproof membranes, there isn’t a risk of rain or moisture seeping through cracks, as there can be with concrete structures over time. Additionally, the 1.5-inch-thick layer of polyurethane foam keeps the temperatures balanced from inside and outside the domes, so no condensation is created on the inside.

A 50,000-ton dome can be constructed in about four to five months, plus a couple of more months to install a pellet reclamation system and aeration in the floors, if it’s part of the engineering plan. After that, it’s ready to be filled with pellets.

Typically, a truck loaded with pellets will pull up to a platform and empty its cargo onto grates. The pellets fall through the grates onto a conveyor, which carries them to the top of the dome, where the process is monitored in a head house that rests on the surface. Inside the dome, a ladder softly delivers the pellets to the floor.

So how long can they remain there before should be moved? “The jury is still out on that, but feedback has been that two to three weeks is optimum,” Roberts says. “There are a lot of opinions out there, and the U.S. Industrial Pellet Association committee on safety and handling and transport is working to gather information on this issue and more, including whether aeration in the floor really works. Typically though, we like to see turnovers from two to four weeks.”

Storage and reclamation systems aren’t the only areas of innovation when it comes to pellet exports. Methods of moving the pellets from reclamation systems onto the waiting ships, as well as controlling dust, have also vastly improved, as evidenced by Samson's (previously B&W) mobile ship loaders.

Loading and Dust Control

Advertisement

Being able to efficiently load pellets onto a ship at high handling rates is essential to a successful export operation, according to Hugo van Benthem at Samson Materials Handling. Who owns the ship loader at a given port varies, but it mostly depends on who owns the storage facility—the port, a pellet plant or a third-party service provider. “Normally we find a little of each,” he says.

Storing pellets at the port is the ideal option to enable schedules to remain as planned, according to van Benthem, as a pellet plant produces at a certain rate over time, but, also wants to load a ship in a very short, specific time frame. “If one wants to load 40,000 tons, the ship has to be loaded at a rate of 500 to 2,000 tons per hour; we do 1,000 tons per hour,” he says. “Even though you want to finish in 40 to 60 hours, overall it can be a month-long production.”

Once reclaimed by a conveying system, Samson provides the link between the pellet conveyors to the ship loader. “Trucks are driven into a reception system and emptied, and the system claims the pellets to fill up the ship loader,” van Benthem explains. “What’s very important here is having the ability to feed big ships; the loader has to be high and big enough to handle the capacity you want to load the ships at.” The company’s ship loaders can serve Panamax and Super Panamax vessels, ships that van Benthem says are ideal size for the U.S. because it’s difficult to get larger-sized vessels in.

Another important component in loading equipment is the ability to control dust. “These pellets are pretty dusty, and you have to be able to extract it,” van Benthem says. “You can’t just convey the pellets through the air into the ship because the amount of dust would be crazy—we have dust filters, encapsulation and extraction on the [ship loader] equipment itself, from when the pellets are fed into ship loader from when they are discharged through a chute, which also has dust equipment on it, onto the ship.”

The mobility of the ship loader provides the opportunity to “trim the holes,” an expression that van Benthem explains means to fill up areas around the pellet pile, creating an even load rather than a giant heap. And once a loading operation is complete, the ship loader can be removed from the area. “They don’t have to become part of the port infrastructure,” van Benthem says. “One of the big drivers for them is that the volumes of pellets going out of one port is not so large that the loader is continuously needed, so it can be moved to free up the loading area. It is also easier to get a permit for, rather than a big, fixed installation, and it can be sold to another place in the future.

The Port of Panama City, Fla., uses a mobile ship loader at its pellet out-loading facility, as does German Pellets at the Port of Port Arthur in Texas. On whether demand for loaders and other export equipment has been increasing or is expected to soon, van Benthem says there has been a lot of interest, but not that much movement. “European policy is driving this—in Europe, 50 percent of consumption is used residentially; the other half is for industrial use, which is subsidized,” he says. “Otherwise, it is not viable. So when politics start to move and utilities start to move, we’ll see more progress.”

Until then, those with stakes in the industry will continue quietly working to perfect the entire pellet export process, tweaking equipment and methods of receiving, storing and loading. “What we’re looking to do is benefit from what the industry has already learned,” O’Keefe adds. “It’s growing rapidly, but still in its embryonic stage. We’re learning from those who have gone before us, and those after us will learn from what we’re doing.”

Author: Anna Simet

Contributions Editor, Biomass Magazine

asimet@bbiinternational.com

701-751-2756

Upcoming Events