Energy Center

April 29, 2011

BY Lisa Gibson

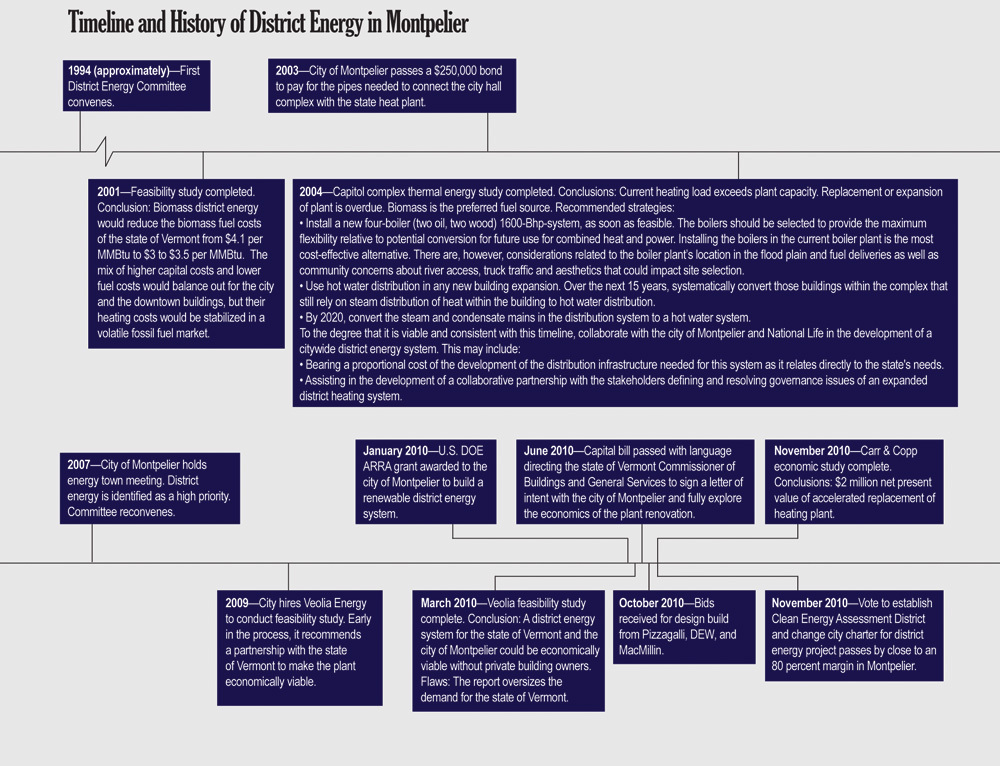

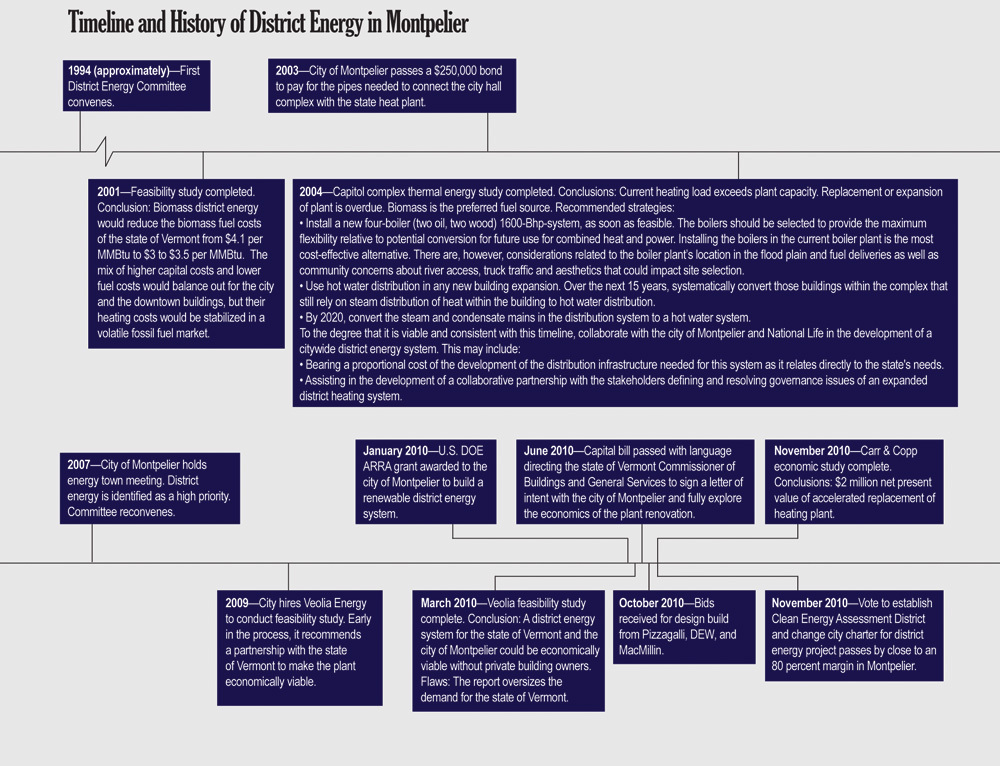

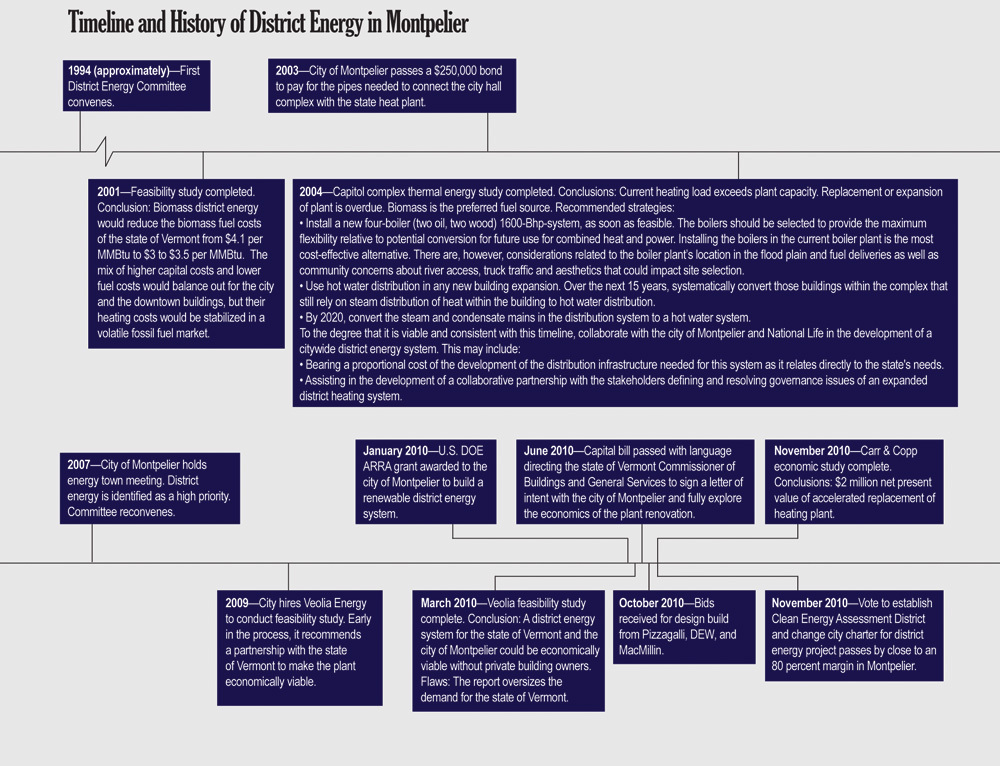

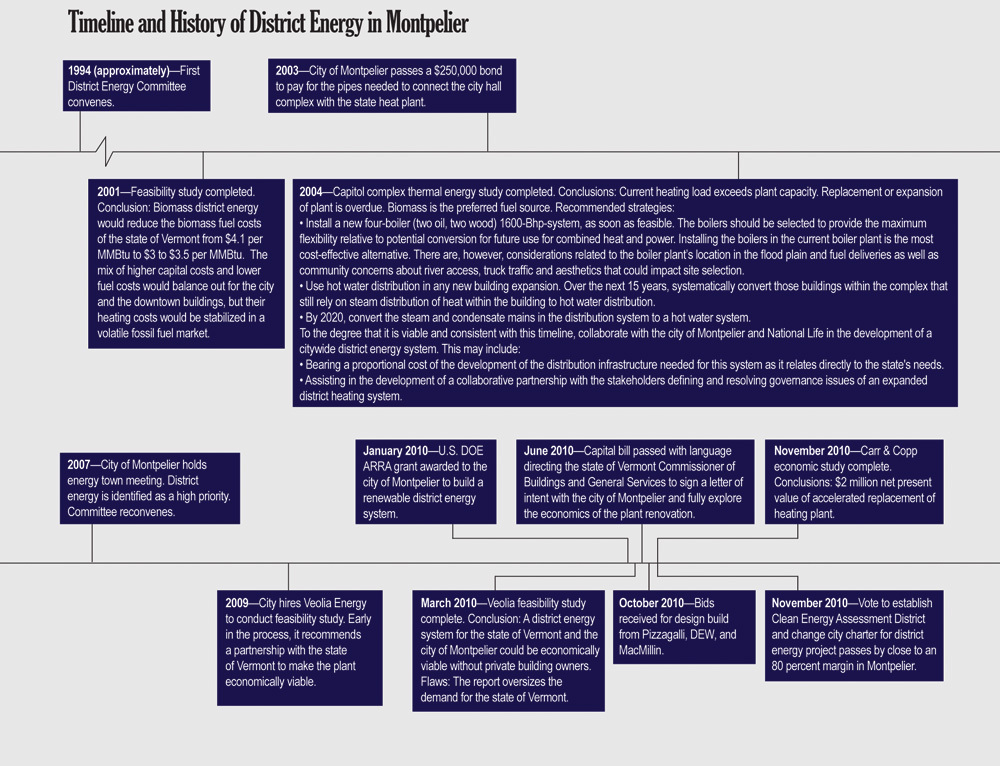

Since the 1940s, Vermont has employed a steam plant to heat its capital complex in downtown Montpelier. Initially coal-fired, the facility was retrofitted for a 60-40 oil-biomass blend in the 1970s. Now, with necessary upgrades and improvements overdue, the next logical step seems to be a complete conversion to biomass feedstock.

So after nearly two decades of discussion and planning, the city and state governments have formally partnered in the small capital city of 8,000 to replace the antiquated state-owned plant with a new, wood chip-fueled facility. In addition, the development plan includes an expansion of the distribution loop to include a number of city buildings, and eventually private commercial and residential structures.

“We’ve had incremental support over the years, but we’ve understood that the state’s plant didn’t have enough capacity to serve the downtown,” says Montpelier City Manager Bill Fraser. “So here’s an opportunity for them to do their efficiency improvements and expand capacity.”

And the impetus that finally got the wheels turning on the idea more quickly? Why, a hefty federal grant, of course. “It just really accelerated all our planning once we had a sense that, boy, this is going to be financially feasible,” says Gwendolyn Hallsmith, director of Montpelier’s Department of Planning and Community Development.

Shooting Distance

In January 2010, with major feasibility studies in progress, the project received an $8 million American Recovery and Reinvestment Act grant that propelled it into a new realm of possibility. “Even though it is very worthwhile and all the project feasibility studies have shown that it is worthwhile, it’s hard for a public entity to come up with the kind of capital you need to do it,” Hallsmith says. “And now with the subsidy from the federal government, we finally are within shooting distance of a project that’s economically feasible.”

The project cost is estimated to be between $18 million and $23 million, but will depend on design decisions that will be made as the plans are rolled out. Although deep into the approval process, the development plans have a ways to go before they are finalized at the city and state levels, including some lingering legislative and budget approvals. If all goes well, however, work on the expanded distribution system could begin this fall, with construction of the new plant after next year’s heating season and operation by 2013, according to Harold Garabedian, project management contractor from Montpelier-based firm Energy & Environmental Analytics.

Advertisement

The new biomass district heating plant will occupy the same space that the current plant does: smack dab in the middle of the downtown historic district and across the street from the state capital complex. The current steam distribution system heating the 17 capital complex buildings will remain operational, but a new hot water distribution loop will connect the new plant with the city’s buildings, including fire and police stations, on the opposite end of the relatively small downtown district. “If you’re building today, hot water is the way to go,” Garabedian says. “However, that state steam system is in place and it’s in good condition, so it’s not economically justifiable at this point to replace it.”

Subsequently, the hot water distribution system will branch out and enable a number of commercial and residential structures in between the two government complexes to hook up to the new loop as well. Eventually, the system will produce up to 41 MMBtu of heat and Garabedian says the expectation is it will heat 1.8 million square feet of the community. It is also possible that the facility could produce a small amount of power, but that aspect of the design is still an open-ended question, Fraser says.

Ownership structure plans for the project dictate that the state will own and operate the new plant as it has the old one, and the city will own the new hot water distribution network that will loop through downtown.

Essential Alliance

The partnership between the state of Vermont and the city of Montpelier is natural, as the two government bodies cross paths on a daily basis as a result of their close proximity in the small community. “We have an ongoing relationship with the state government,” Fraser says. “They are a major presence in our town and we interact with them regularly.” That existing interaction, cooperation and trust is crucial to a partnership meant to facilitate such a project, Fraser emphasizes, adding that the city and the state Department of Buildings and General Services discussed the plans on numerous occasions before the pivotal grant was awarded.

The city had approached the state with the proposition of applying for an ARRA grant to push the project along, after years of mutual discussion and planning hit common road bumps including financing and logistics, Fraser recalls. “We thought, ‘This might be the time to finally do this distributed energy project we’ve been talking about for a long time,’” he says. “I think [the federal government] found the city-state partnership intriguing.” Garabedian touts the project as the first district heating endeavor in Vermont to marry state and city governments into one combined effort. “I think the partnership is essential,” Fraser says. The Biomass Energy Resource Center, a national organization, has also lent a helping hand in the development process.

Advertisement

Needless to say, the new plant and distribution loop will bring a plethora of benefits to both city and state governmental agencies and the community of Montpelier. Besides the fact that the update will more than double the heat output and allow more advanced emission controls, it also will help reduce the number of oil-burning furnaces in the downtown district, offering a cleaner and local energy alternative. “We believe that will stabilize our fuel prices over time,” Fraser says. Garabedian agrees and sites analyses that show the price of oil fluctuates much more erratically than that of local woody biomass.

In addition, the new system will mean less maintenance for connected structures and a savings of 10 to 20 percent on heating bills, Hallsmith says. That money also will go to the local economy instead of foreign oil producers. “It’s got all these elements people are looking for in projects,” Garabedian says.

While biomass energy projects across the country have struggled with local opposition recently and Vermont is no exception, the Montpelier district heating plant has had tremendous support from the community. In fact, three citizen votes on the project all passed overwhelmingly, the most recent by 80 percent, Hallsmith says. “Every vote has passed by wide margins.”

She attributes that support partially to the fact that the system is not entirely new, but a replacement to an existing one. The welcoming reception from citizens is good news for the project because a city bond vote is required for final approval, Fraser says.

The Model

In determining the best-suited technology for its new district heating plant, the partners flip-flopped between innovative processes and common, proven ones. Suspension biomass-burning technologies were considered and almost chosen, but were bumped out of the plans by a simple combustion technology thought to be a better and more reliable fit for this particular project, Garabedian says.

“[Suspension combustion] is a very intriguing technology, but we decided we probably aren’t the best people to try that,” he says. Suspension combustion is used in Sweden, he explains, but is usually paired with wood processing operations that generate large amounts of wood dust. “A more proven, more mainstay technology probably serves what we’re doing given our size and location,” Garabedian explains, adding that because Vermont is “off the beaten path” and not well-traveled, concerns were raised about servicing a new technology.

If the system is approved and developed, it will consume between 10,000 and 15,000 tons of wood chips per year, depending again on final design decisions. Oil boilers will also be in place as a backup. No agreements are in place for the biofuel feedstock at the new plant, but the existing blended feedstock plant does have some current contracts for its wood chips, Garabedian says. The developers envision bids and fuel contracts with third-party sustainability verification, and regular deliveries by truck about twice a day with up to five or six per day during peak heat use. The feedstock will be delivered already chipped and the facility will have the capacity to store up to five days worth to cover any delivery disruptions caused by wet weather or other factors. Fortunately, an infrastructure for a wood chip supply chain is quickly evolving in Vermont, Garabedian says, further confirming that the time is now to develop Montpelier’s long-awaited biomass district heating system.

“There are a lot of people who would really like to see this happen,” he says, adding that the community project is advancing in a state that already employs a few university campus district heating systems. The time is right, in the midst of energy policy struggles, to move up to community systems and the project is a step in the right direction, he adds. “[We’re] looking at it in terms of how does a small community look to the future and make its contribution to energy independence, sustainability. If the project can move forward here successfully, I think it’ll be a great model for a lot of other communities throughout the country.”

Author: Lisa Gibson

Associate Editor, Biomass Power & Thermal

(701) 738-4952

lgibson@bbiinternational.com

Upcoming Events