Expanding the Feedstock Portfolio

November 20, 2009

BY Susanne Retka Schill

Another bumper crop promises ample soybean supplies for all of the crop's myriad uses. In October, USDA was projecting a record 3.25 billion bushel production on 77 million planted acres, helping to settle fears that a late maturing soybean crop would be hurt by early frosts. Still, market jitters continued as farmers struggled to bring in the crop during breaks in fall rains amid reports of surprisingly good yields. "Iowa and Illinois's average temperature in July was about as cool as it has ever been," says Darrel Good, University of Illinois marketing specialist. "Cool summers are considered good for soybeans, but the question was-can it be too cool." Early concerns about disease affecting this year's yields were offset by positive factors, and Good says early reports of large seed sizes were contributing to the good yields.

While harvest rains kept pressure on the markets, at the same time reports emerged that the South American soybean crop being planted could be a big one as the region recovers from its worst drought in decades. "If the South American crop lives up to early forecasts, Brazil and Argentina are expanding soybean areas," Good reports. When the South American harvest approaches, he expects Chinese buying of American soy to slow down in anticipation. In a reversal of the typical market lows occurring during harvest, Good suggests this year prices may be at their marketing season (Sept. 1 to Aug. 31) high during harvest time, dropping as the South American harvest approaches. In its October report, USDA projected season average prices for soybeans in a range of $8 to $10 per bushel and soybean meal at $245 to $305 per ton. The soybean oil price range for 2009-'10 is projected to average between 32 to 36 cents per pound.

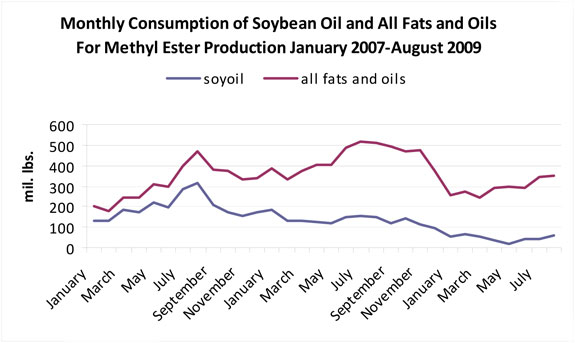

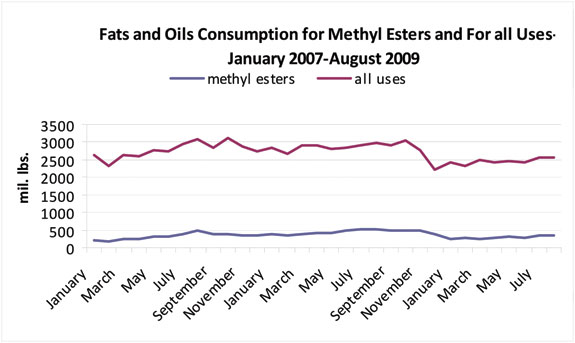

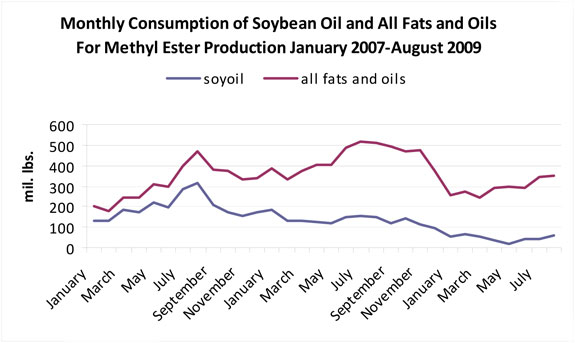

Bumper crops used to send corn and soybean prices into the basement, but the growth in biofuels demand for the two biggest crops in U.S. agriculture has used up the surplus and kept carryover volumes modest, even with the large crops of recent years. In turn, corn and soybeans prices now follow trends in crude oil prices. The rebound in the energy market the past few months is one of the factors supporting soy prices, Good says. Soy oil used for methyl esters dropped to 1.85 billion pounds last year, almost half that of the 3.2 billion pounds used for methyl esters in the 2007-'08 marketing year. USDA is projecting soy oil use in biodiesel will climb back to 2.1 billion pounds in the current marketing year. Biodiesel use at about 10 percent of the total soy oil supply is not as great as ethanol's share of one-third of the U.S. corn crop, but soy utilization for methyl esters is high enough where changes in biodiesel demand for the crop has an impact. "A 300 to 500 million pound swing makes a difference in the market," Good says. Ethanol's impact on the corn market affects soybeans too, since the two crops vie for acreage each spring, keeping their relative values in balance.

As the biodiesel market has grown in its market share, traders are seeing the impact. Brian Engel, vice president of trading with Omaha, Neb.-based Tenaska Biofuels, says he now sees soy oil markets pricing themselves in and out of biodiesel. As soon as the price drops a bit, biodiesel use goes up, but only briefly, until the market boosts it back up beyond biodiesel profitability. Engel says that range amounts to about 5 cents per pound, which translates to a 35 cent to 40 cent per gallon range. With diesel markets staying fairly strong, Engel says this fall "we needed to see 32 cent to 33 cent soy oil to move any significant volumes of soybeans." Whenever prices move above that, he says, only the base demand to cover mandated uses and state incentives can afford to be in the market. In August through the first half of October, soy oil prices dropped into the low 30s, with cash prices in some locations dipping to just under 30 cents a pound, he notes. "Soy oil got priced in and we saw pretty good volumes of biodiesel sales through December," Engel says, adding that this kind of pricing shift tends to play out in sales on a quarterly basis. Seasonal trends are also clearly in place, with animal fats and waste oil demand dropping as cold weather approaches and interest in soy oil and even premium canola oil going up for biodiesel. Even palm oil, which often used to trade at a discount to soybean oil, is seeing the impact of new biodiesel capacity in the two major producing nations, Indonesia and Malaysia. Whenever prices begin to drop, biodiesel production begins utilizing more until the prices move back up. What's happening in palm oil prices, in turn, impacts the oleochemical market (soaps and detergents), which is a major use for U.S. animal fats, along with energy for feed rations and biodiesel.

Seeking Alternatives

The complex relationship among the major feedstock sources for biodiesel is keeping global markets strong, but in the face of growing global demand for edible oils from increasing populations with improved diets, there is increased pressure to find nonfood alternatives. Algae's potential for supplying large volumes of biofuel feedstocks is tantalizing, but still in the future. Reports of jatropha biodiesel production in Africa and Asia are beginning to emerge, and will possibly begin to reach significant volumes in the next year or two.

In the U.S., the crop most likely to become a significant new feedstock in the next few years is camelina. After a dip in farmer interest when the wheat market was exceptionally strong, camelina acres continue to grow, and could possibly top 100,000 planted acres this year in Montana and surrounding states and provinces. The crop is also being widely tested across the U.S. and Canada and in a number of other countries.

The major attraction for camelina is its sustainability quotient. An oilseed in the brassica family, camelina gives impressive yields on modest rainfalls with the potential to be added into crop rotations without displacing other crops. One test plot in the Pacific Northwest yielded 2,700 pounds of seed on 20 inches of rainfall, reports Sam Huttenbauer, CEO of Great Plains-the Camelina Co. However, the average yield across the arid regions where it is currently grown is roughly half that. Field trials being conducted in upstate New York and Wisconsin are seeing yields range between 1,000 pounds per acre and 1,400 pounds per acre, according to Innovation Fuels Inc. CEO John Fox. In Montana, where the crop development originated, crop breeders expect that yields of 2,000 pounds per acre will be attainable as varieties improve and agronomic practices are refined.

Other important factors for camelina's expansion are falling into place. Camelina meal has been approved for use in broiler rations and at press time, Huttenbauer reported the approval process for use in egg-layer rations was close. A herbicide for weed control is available and the crop can now be covered by crop insurance. Next on the list for Great Plains is the development of varieties that can tolerate a common herbicide used in the Pacific Northwest. Herbicide carryover in the soil has made it difficult to rotate sensitive broadleaf crops like camelina with the dominant wheat crop. Great Plains and Sustainable Oils Inc., the two main companies promoting the crop for biodiesel production, are both making progress in contracting acres and developing new markets, including the aviation market for bio-based jet fuels.

Pennycress

Another promising new crop is gaining ground. Pennycress, like camelina, promises yields in the 2,000 pound per acre range, high oil content and the ability to fit into rotations without displacing existing food crops. In Illinois, Peter Johnson, chief technology officer for Biofuels Manufacturers of Illinois LLC, reports its Pennycress Partners outreach to farmers has gained important support in the leadership of Illinois Soybean Association past president, Brad Glenn. Hopes for more than 2,000 acres to be seeded this fall were dampened by the late corn harvest, since the most common rotation is to seed pennycress in the fall following corn to be harvested in the spring before planting soybeans. Johnson estimated about half that would be planted, some of it into wheat ground. BMI is still awaiting financing on a proposed biodiesel plant in Peoria County, Ill. "We're making progress on a state loan guarantee, and we've got bankers watching that progress and equity investors watching both [state and bank support for the project]," Johnson says.

One downside for pennycress is finding a use for the meal, which is not suitable for feed. BMI is working with USDA researchers to develop a pyrolysis-based process to convert pennycress wet cake after oil extraction into bio-oil and biochar. A ton of pennycress seed will yield 95 gallons of oil for use in the biodiesel process plus 95 gallons of bio-oil from wet cake, Johnson says.

Further east, biodiesel producer Innovation Fuels is also working to develop pennycress. CEO John Fox reports they have close to 1,000 acres of field trials in five regions of upstate New York, as well as three regions in Wisconsin. "We're hitting yields of 1,000 to 1,500 pounds per acre of seed," he says. The company expects to be processing a significant amount of pennycress oil in its Newark, N.J., biodiesel plant in 2010. The company recently relocated its corporate headquarters to Syracuse, N.Y., to facilitate its work with Cornell University in developing the crop. The partners are also working on higher value uses for the meal.

Tree Oils

While jatropha is the oil-bearing tree crop most often discussed, other tree crops are being evaluated. One American company, Biofuels Africa, is focusing its attention on the croton tree, a large forest canopy tree producing an oilseed traditionally used for heating and lighting. Plantings in Tanzania are expected to begin bearing in 2010 and the company recently held discussions in Kenya about the potential for using the croton tree for erosion control along with oil production. Christine Adamow, Biofuels Africa director, says they expect to have their first harvest of about 10 tons of oil next year, with production ramping up in subsequent years. Projections call for 200 trees per acre to yield between 70 to 110 pounds each. With 30 percent oil content in the seeds, croton plantations could yield between 5,000 and 7,000 pounds of oil per acre annually. "Our goal is to take the oil and modify it in the least environmentally demanding process possible," she adds. "We'll not be using transesterification."

In the U.S., work on the tallow tree continues in Louisiana. Gary Breitenbeck, a researcher in the Louisiana State University's AgCenter School of Plant, Environmental and Soil Sciences, believes the tallow tree will fill a valuable niche in the South being able to grow on wet, salt-impacted, infertile soils unsuitable for row crops. "We have pretty compelling evidence that from mature trees we can get 1,000 gallons of oil per acre at less cost than soy oil," he says. Within a year, he believes his team will have developed a micro propagation technique to clone high-yielding trees. The team is also finishing a study on oil composition and has developed a process to separate the waxy and kernel oils found in the seeds. Three partners have emerged to back his research. Hal Wrigley with Ecogy Biofuels LLC in Estill, S.C., Jeff Hassannia with Diversified Energy Corp. and Louisiana consultant Scott Nesbit have formed CTT Bioenergy LLC to commercialize the tallow tree.

For any of these promising alternative feedstocks to have a real impact on biodiesel margins, they will have to produce oils at a cost below the traditional feedstocks and do so in sufficient volumes. Even if camelina tops 100,000 acres this coming year, it would barely supply a good-sized biodiesel plant. One 25 MMgy biodiesel producer figures it needs soybeans from 1,700 acres per day to keep its plant going at full capacity. It will take time before new alternatives will take the pressure off the current biodiesel feedstocks.

Susanne Retka Schill is assistant editor of Biodiesel Magazine. Reach her at (701) 738-4922 or sretkaschill@bbiinternational.com.

While harvest rains kept pressure on the markets, at the same time reports emerged that the South American soybean crop being planted could be a big one as the region recovers from its worst drought in decades. "If the South American crop lives up to early forecasts, Brazil and Argentina are expanding soybean areas," Good reports. When the South American harvest approaches, he expects Chinese buying of American soy to slow down in anticipation. In a reversal of the typical market lows occurring during harvest, Good suggests this year prices may be at their marketing season (Sept. 1 to Aug. 31) high during harvest time, dropping as the South American harvest approaches. In its October report, USDA projected season average prices for soybeans in a range of $8 to $10 per bushel and soybean meal at $245 to $305 per ton. The soybean oil price range for 2009-'10 is projected to average between 32 to 36 cents per pound.

Bumper crops used to send corn and soybean prices into the basement, but the growth in biofuels demand for the two biggest crops in U.S. agriculture has used up the surplus and kept carryover volumes modest, even with the large crops of recent years. In turn, corn and soybeans prices now follow trends in crude oil prices. The rebound in the energy market the past few months is one of the factors supporting soy prices, Good says. Soy oil used for methyl esters dropped to 1.85 billion pounds last year, almost half that of the 3.2 billion pounds used for methyl esters in the 2007-'08 marketing year. USDA is projecting soy oil use in biodiesel will climb back to 2.1 billion pounds in the current marketing year. Biodiesel use at about 10 percent of the total soy oil supply is not as great as ethanol's share of one-third of the U.S. corn crop, but soy utilization for methyl esters is high enough where changes in biodiesel demand for the crop has an impact. "A 300 to 500 million pound swing makes a difference in the market," Good says. Ethanol's impact on the corn market affects soybeans too, since the two crops vie for acreage each spring, keeping their relative values in balance.

As the biodiesel market has grown in its market share, traders are seeing the impact. Brian Engel, vice president of trading with Omaha, Neb.-based Tenaska Biofuels, says he now sees soy oil markets pricing themselves in and out of biodiesel. As soon as the price drops a bit, biodiesel use goes up, but only briefly, until the market boosts it back up beyond biodiesel profitability. Engel says that range amounts to about 5 cents per pound, which translates to a 35 cent to 40 cent per gallon range. With diesel markets staying fairly strong, Engel says this fall "we needed to see 32 cent to 33 cent soy oil to move any significant volumes of soybeans." Whenever prices move above that, he says, only the base demand to cover mandated uses and state incentives can afford to be in the market. In August through the first half of October, soy oil prices dropped into the low 30s, with cash prices in some locations dipping to just under 30 cents a pound, he notes. "Soy oil got priced in and we saw pretty good volumes of biodiesel sales through December," Engel says, adding that this kind of pricing shift tends to play out in sales on a quarterly basis. Seasonal trends are also clearly in place, with animal fats and waste oil demand dropping as cold weather approaches and interest in soy oil and even premium canola oil going up for biodiesel. Even palm oil, which often used to trade at a discount to soybean oil, is seeing the impact of new biodiesel capacity in the two major producing nations, Indonesia and Malaysia. Whenever prices begin to drop, biodiesel production begins utilizing more until the prices move back up. What's happening in palm oil prices, in turn, impacts the oleochemical market (soaps and detergents), which is a major use for U.S. animal fats, along with energy for feed rations and biodiesel.

Seeking Alternatives

The complex relationship among the major feedstock sources for biodiesel is keeping global markets strong, but in the face of growing global demand for edible oils from increasing populations with improved diets, there is increased pressure to find nonfood alternatives. Algae's potential for supplying large volumes of biofuel feedstocks is tantalizing, but still in the future. Reports of jatropha biodiesel production in Africa and Asia are beginning to emerge, and will possibly begin to reach significant volumes in the next year or two.

In the U.S., the crop most likely to become a significant new feedstock in the next few years is camelina. After a dip in farmer interest when the wheat market was exceptionally strong, camelina acres continue to grow, and could possibly top 100,000 planted acres this year in Montana and surrounding states and provinces. The crop is also being widely tested across the U.S. and Canada and in a number of other countries.

The major attraction for camelina is its sustainability quotient. An oilseed in the brassica family, camelina gives impressive yields on modest rainfalls with the potential to be added into crop rotations without displacing other crops. One test plot in the Pacific Northwest yielded 2,700 pounds of seed on 20 inches of rainfall, reports Sam Huttenbauer, CEO of Great Plains-the Camelina Co. However, the average yield across the arid regions where it is currently grown is roughly half that. Field trials being conducted in upstate New York and Wisconsin are seeing yields range between 1,000 pounds per acre and 1,400 pounds per acre, according to Innovation Fuels Inc. CEO John Fox. In Montana, where the crop development originated, crop breeders expect that yields of 2,000 pounds per acre will be attainable as varieties improve and agronomic practices are refined.

Other important factors for camelina's expansion are falling into place. Camelina meal has been approved for use in broiler rations and at press time, Huttenbauer reported the approval process for use in egg-layer rations was close. A herbicide for weed control is available and the crop can now be covered by crop insurance. Next on the list for Great Plains is the development of varieties that can tolerate a common herbicide used in the Pacific Northwest. Herbicide carryover in the soil has made it difficult to rotate sensitive broadleaf crops like camelina with the dominant wheat crop. Great Plains and Sustainable Oils Inc., the two main companies promoting the crop for biodiesel production, are both making progress in contracting acres and developing new markets, including the aviation market for bio-based jet fuels.

Pennycress

Another promising new crop is gaining ground. Pennycress, like camelina, promises yields in the 2,000 pound per acre range, high oil content and the ability to fit into rotations without displacing existing food crops. In Illinois, Peter Johnson, chief technology officer for Biofuels Manufacturers of Illinois LLC, reports its Pennycress Partners outreach to farmers has gained important support in the leadership of Illinois Soybean Association past president, Brad Glenn. Hopes for more than 2,000 acres to be seeded this fall were dampened by the late corn harvest, since the most common rotation is to seed pennycress in the fall following corn to be harvested in the spring before planting soybeans. Johnson estimated about half that would be planted, some of it into wheat ground. BMI is still awaiting financing on a proposed biodiesel plant in Peoria County, Ill. "We're making progress on a state loan guarantee, and we've got bankers watching that progress and equity investors watching both [state and bank support for the project]," Johnson says.

One downside for pennycress is finding a use for the meal, which is not suitable for feed. BMI is working with USDA researchers to develop a pyrolysis-based process to convert pennycress wet cake after oil extraction into bio-oil and biochar. A ton of pennycress seed will yield 95 gallons of oil for use in the biodiesel process plus 95 gallons of bio-oil from wet cake, Johnson says.

Further east, biodiesel producer Innovation Fuels is also working to develop pennycress. CEO John Fox reports they have close to 1,000 acres of field trials in five regions of upstate New York, as well as three regions in Wisconsin. "We're hitting yields of 1,000 to 1,500 pounds per acre of seed," he says. The company expects to be processing a significant amount of pennycress oil in its Newark, N.J., biodiesel plant in 2010. The company recently relocated its corporate headquarters to Syracuse, N.Y., to facilitate its work with Cornell University in developing the crop. The partners are also working on higher value uses for the meal.

Tree Oils

While jatropha is the oil-bearing tree crop most often discussed, other tree crops are being evaluated. One American company, Biofuels Africa, is focusing its attention on the croton tree, a large forest canopy tree producing an oilseed traditionally used for heating and lighting. Plantings in Tanzania are expected to begin bearing in 2010 and the company recently held discussions in Kenya about the potential for using the croton tree for erosion control along with oil production. Christine Adamow, Biofuels Africa director, says they expect to have their first harvest of about 10 tons of oil next year, with production ramping up in subsequent years. Projections call for 200 trees per acre to yield between 70 to 110 pounds each. With 30 percent oil content in the seeds, croton plantations could yield between 5,000 and 7,000 pounds of oil per acre annually. "Our goal is to take the oil and modify it in the least environmentally demanding process possible," she adds. "We'll not be using transesterification."

In the U.S., work on the tallow tree continues in Louisiana. Gary Breitenbeck, a researcher in the Louisiana State University's AgCenter School of Plant, Environmental and Soil Sciences, believes the tallow tree will fill a valuable niche in the South being able to grow on wet, salt-impacted, infertile soils unsuitable for row crops. "We have pretty compelling evidence that from mature trees we can get 1,000 gallons of oil per acre at less cost than soy oil," he says. Within a year, he believes his team will have developed a micro propagation technique to clone high-yielding trees. The team is also finishing a study on oil composition and has developed a process to separate the waxy and kernel oils found in the seeds. Three partners have emerged to back his research. Hal Wrigley with Ecogy Biofuels LLC in Estill, S.C., Jeff Hassannia with Diversified Energy Corp. and Louisiana consultant Scott Nesbit have formed CTT Bioenergy LLC to commercialize the tallow tree.

For any of these promising alternative feedstocks to have a real impact on biodiesel margins, they will have to produce oils at a cost below the traditional feedstocks and do so in sufficient volumes. Even if camelina tops 100,000 acres this coming year, it would barely supply a good-sized biodiesel plant. One 25 MMgy biodiesel producer figures it needs soybeans from 1,700 acres per day to keep its plant going at full capacity. It will take time before new alternatives will take the pressure off the current biodiesel feedstocks.

Susanne Retka Schill is assistant editor of Biodiesel Magazine. Reach her at (701) 738-4922 or sretkaschill@bbiinternational.com.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Upcoming Events