Feedstock: The Single, Biggest Contributor

PHOTO: Tim Portz, BBI International

May 12, 2016

BY Katie Fletcher

Combine a number of dependent variables, many characterized by uncertainty―diesel cost, stumpage and weather, to name a few―and you’re on your way to linking the complexities that accompany forecasting occurrences in the pellet feedstock supply chain. Price is a function of multiple market drivers. Pellet demand, in and of itself, does not drive inventory or price changes, but a combination of supply and demand factors, such as restrictions in the supply chain and weather, does. Since the beginning of the year, pellet mills and sawmills have been trying to figure out how to stop the supply infrastructure from really being hurt, and sawmills are reluctant to move pricing too much on wood supplies. “There is downward pressure right now, everyone’s feeling it,” says William Perritt, senior editor of the North American Woodfiber & Biomass Markets report with RISI Inc.

After the housing crash in 2008, supply infrastructure for the logging force was decimated, leading to retirements, attrition and less efficient operations closing shop. Efficiency and market access were key during the lean times, Perritt says. Over time, equipment in the field continued to age. However, in the past 18 to 24 months, there has been reinvestment, Perritt says, and now many companies are geared up with newer forwarders, processors, skidders, etc., while the industry faces another wave of impediments. Warm weather and low fuel oil have nearly halted pellet production for the domestic heat market, some retraction in pulp and paper production has occurred and certain sawmills have closed because they can’t get rid of residual material. “Sawmilling has grown from an industry that depended on its finished products for all of its profit to getting accustomed to having a market for chips, shavings and sawdust, and a lot of them have survived on those things once they picked up in significant value after 2005-‘06, moving forward with pellets and biomass energy,” Perritt explains. “Now, they’re facing stockpiles of raw material.”

Many pellet producers and pulpwood buyers have tried to stay the course on pricing, as much as they can, to not hurt the remaining suppliers in the field, Perritt believes, but there are always those who are shortsighted and may take advantage of the situation. “You don’t want to alienate suppliers or cause them to go under for fear that down the road when things turn around they could find themselves shunned from the marketplace,” Perritt says. “There is sort of a dance that is going on right now.”

Across North America, this dance has taken place in quarter one of the year and has moved into quarter two, in some regions more than others, but, even by the time this is read, the situation may be subsiding in many areas. Raw material is the single, biggest contributor to densified fuel, says pellet producer T.J. Morice, vice president of marketing and operations with Wisconsin-based Marth Companies. Thus, when a number of market drivers change the value of raw material, it will impact the product that material creates. The downward pricing trend on feedstock reported during March may allow some producers to price their pellets more competitively in the future.

Industry Update

It’s been the tale of two heating seasons for regions consuming pellets for heat, with the tale not ending the way in which producers had hoped. Political uncertainty, both stateside and overseas, makes it hard to predict what role pellets will play for industrial power generation. Additionally, pellet prices and exchange rates have kept U.S. producers from serving European spot-heating markets. As the pellet industry grows, producers turn their attention to securing a sustainable feedstock supply chain for both an increasing export market and local heat markets that must weather cyclical upturns and downturns.

The pellet industry got its start in the 70s, in part, because of the oil embargo making pellets an economically attractive fuel. Sustained low fuel prices over the next few decades kept the industry from taking off, but fuel oil started climbing in the early 2000s and with it the demand for pellet fuel. Increased fossil fuel prices over the past decade provided the foundation the pellet industry needed to grow upon. “Now, it’s a great concern because this industry is truly cyclical based upon what oil prices are doing,” says Chad Schumacher, general manager of Superior Pellet Fuels LLC.

In January, oil prices hit a low of nearly $25 a barrel and home heating oil was available at $1.39 a gallon. This price point meant wood pellets were no longer a low-cost option, and these falling commodity prices left stores and retailers with diminishing value on purchased wood pellets. Retailers are now left avoiding substantial commitments for next season or waiting on the sidelines to see what happens. Fossil fuel prices could shoot up as quickly as they went down, however, and since January crude oil has increased to nearly $44 a barrel.

Advertisement

Weather, as another cyclical and unpredictable factor, compounds the uncertainty. Christian Bach, founder of North American Biomass, notes that it was warmer on Christmas Eve in New England than on the Fourth of July—there was a 20 percent decrease in weather heating days that has led to an oversupply in the supply chain. Inventory is stacking up, and only time will tell what the shakeout will be. If you follow weather predictions, the current El Niño (warm) is expected to continue through spring or early summer, but meanwhile the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration issued a La Niña (cold) watch, reporting conditions are favorable for La Niña to emerge within six months.

Even though it’s hard to avoid getting caught up in the conditions here and now, one can look at the big picture and find numerous bright spots in past progress and future potential for the pellet industry. Over the past 10 years, industry as a whole has posted double-digit compounded growth, with 30 million tons produced globally last year. New plants have come online and more than 8 million additional tons of pellets will be needed by 2019 for European power generation. The U.S. heating pellet industry has experienced expanded state policy support; combustion technology improvement, with pellets adequately able to serve air quality particulate matter regulations; wider acceptance of fuel standards; a maturing overall supply chain, addressing “shortages”; and healthy consolidation within the industry. But, for now, Bach identifies what is needed for this season: lower pricing from producers, lower expectations from traders and lower margins from retail sales. Actions that could help U.S. local heat markets include the passing of the Biomass Thermal Utilization Act and extending tax credits, putting biomass heating on parity with other renewables.

Wood Basket Variance

East to west, wood fiber baskets and the markets they serve vary, but when market dynamics like low fossil fuel and warm weather span nationwide, commonalities in how the regions are impacted can surface. Perhaps evidenced by the fact that producers operating in the heart of Alaska, central Wisconsin and southern New York concur when they say their raw material prices have dropped and, in some cases, dropped significantly.

Duane Terwilliger, manager with Instant-Heat Wood Pellets in Addison, New York, says their steady suppliers don’t necessarily like the change in prices but understand that it is important to survive this market where there are ups and downs. “We held out as long as we could on lowering the feedstock price, but finally had to make adjustments in pricing and manufacturing of pellets, because inventory levels are too high,” Terwilliger says.

Schumacher’s Superior Pellet Fuels 35,000-ton-capacity plant in Fairbanks, Alaska, sources about 90 percent Spruce softwood, with some Aspen. Interior Alaska’s timber industry is small. In fact, Schumacher says, really the only material competing for his raw material supply is the firewood market. As a producer in Alaska, Schumacher varies from his industry colleagues in that he experiences some of the highest raw material, labor and power costs in the country. The Fairbanks plant hosts an open yard for buying product in round log form from local harvesters, but in order to guarantee supply on an annual basis the company partners with a local harvesting operation that puts the raw material into log form at a landing, after which it is transported by Schumacher and his crew. “We make sure we have the material in the yard by controlling our own destiny in that aspect,” Schumacher says. By doing this, he adds, the company can experience the direct cost of operating in the woods and transporting. Schumacher says in some situations he directly negotiates for a timber sale held by the state of Alaska, and in other cases, the logger negotiates depending on the area of the state it falls in. “That gives me an immediate understanding of the stumpage value that needs to be attributed to that raw material procurement cost,” Schumacher explains.

This cost understanding presents an opportunity Superior Pellet Fuels enjoys to more effectively navigate market dynamics. “In today’s situation—when I have an absolutely full yard―the laws of supply and demand come into play,” Schumacher says. “A decrease in the purchase price still allows loggers to bring the material to market and the lower price justifies the financial investment on my end.”

Overall, the Alaskan operation has experienced a reduction of 15 percent in raw material procurement costs. Rather than reducing the price more, however, Schumacher says the facility will probably stop accepting raw material for a time, partly due to the wet seasonal breakup that will slow logging operations as well as the amount of volume in the yard. “At today’s production levels, I have three years of raw material supply sitting in my yard, and really it is too much,” Schumacher says. “I’m at risk now of seeing the integrity of that raw material deteriorate to the point where it could cost me in the long run in regards to the quality of my pellets. An increase in market demand this next heating season would solve this concern.”

Advertisement

Producers across North America are in similar situations, and some who can produce are doing so merely to maintain supplier relationships. For producers who utilize residual material from sawmilling operations, they realize that while they may not need material from the sawmill short-term, they need to maintain long-term partnerships with their mills to guarantee future supply.

Some producers, however, do not have the financial stamina to continue purchasing raw material and running their operations to sustain suppliers. Sawmills’ dependency on their pulpwood and pellet producer customers could impact the whole timber industry. “The pellet industry is a large user of many of these byproducts, and when we can't utilize them effectively, as many have come to rely on cost, everybody panics,” Morice says. “In some cases, they may have limited additional markets or nowhere else to go with the byproducts so you could potentially shut down certain mills.” Morice adds that many mills employ a high number of people and when all of a sudden they go from making $20 to $40 a ton on their byproduct to having to spend money to dispose of it, that's a financial game changer.

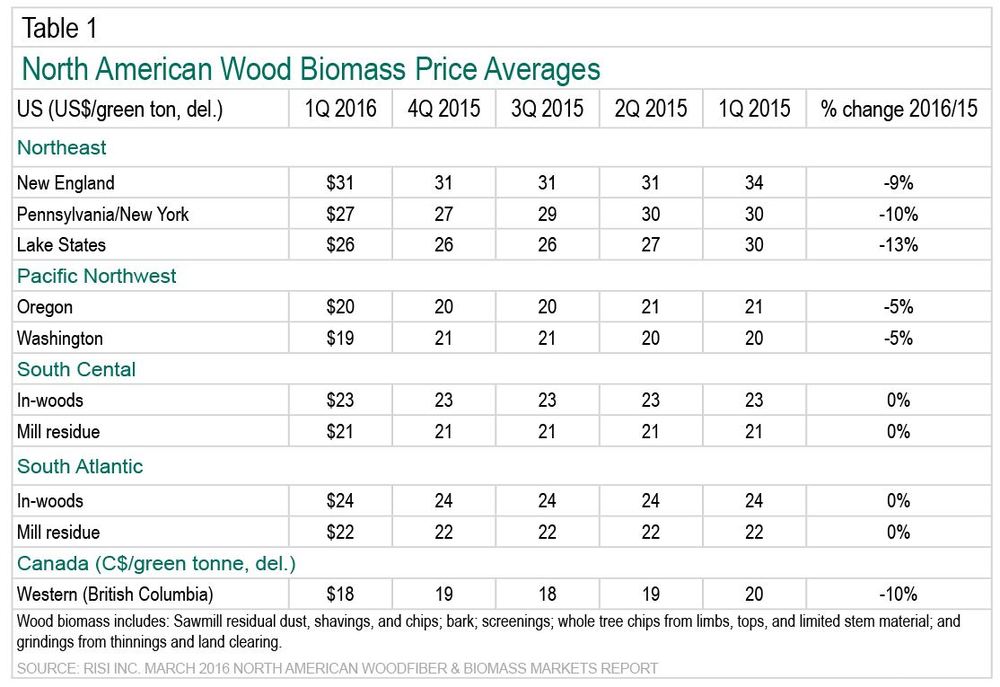

Pulp and paper mill closures also factor into wood price. William Strauss, CEO of FutureMetrics, says, “In Maine, where I live, we’ve had five pulp mill closures in the past two years, so that’s a huge loss of demand from pulpwood.” He adds that “over 2 million green tons per year of pulpwood demand has evaporated from the market, so wood prices have dropped dramatically.” Strauss says this is actually good for pellet producers because the cost of making a pellet has also dropped dramatically. Wood prices in Maine for residuals in March, according to Strauss, were down $5 to $10 per ton, which translates into roughly $10 to $20 lower cost of materials per ton of pellets (assuming about 2-1 green wood to pellets ratio).

The pulp and paper industry in Maine has experienced a long, steady decline and it’s more recently that there’s been a pretty heavy decline in wood demand, plummeting prices, Strauss says. He predicts that if heating oil stays below $2 per ton, producers will lower their current prices (around $190 to $250 per ton, depending on region) by at least $10 to $20 per ton to make pellets more competitive with heating oil. At the end of March, Strauss reported Maine heating oil was $1.45 per gallon. At the current pricing, he says, heating oil would have to climb to $2.05 per gallon for the two fuels to be at parity.

Price Point

As feedstock is the single, largest expense that any plant has, Morice says, if that goes down, by rights the end product should go down. Schumacher believes the raw material price doesn’t really help anyone today, but it enables the industry to be in a much better position in the foreseeable future. “Everything about having a lot of raw material and cheaper raw material coming into the yard is an economic advantage,” he says. “It’s a large risk because it’s a financial commitment, but it’s a huge advantage for that pellet producer to improve their efficiency, improve their raw material consumption and decrease the cost of that raw material supply.”

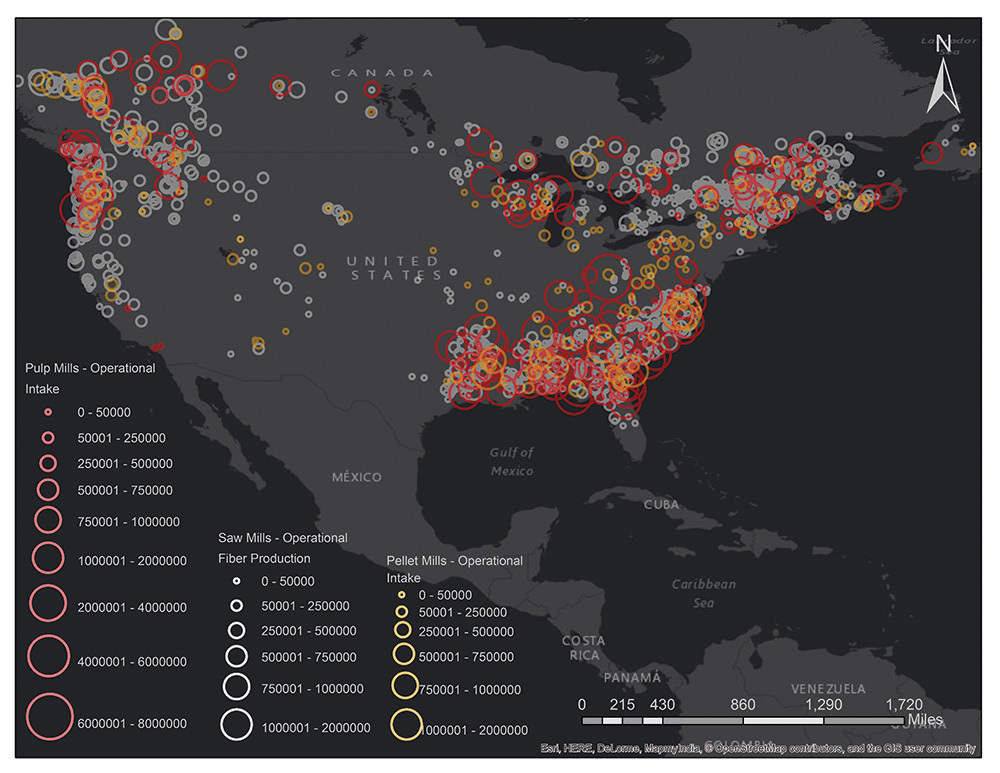

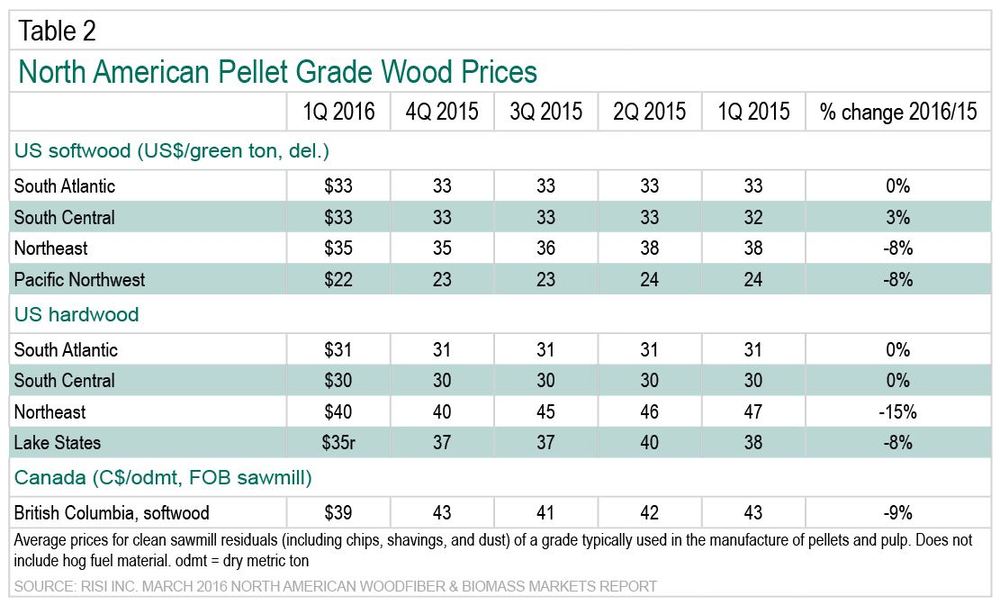

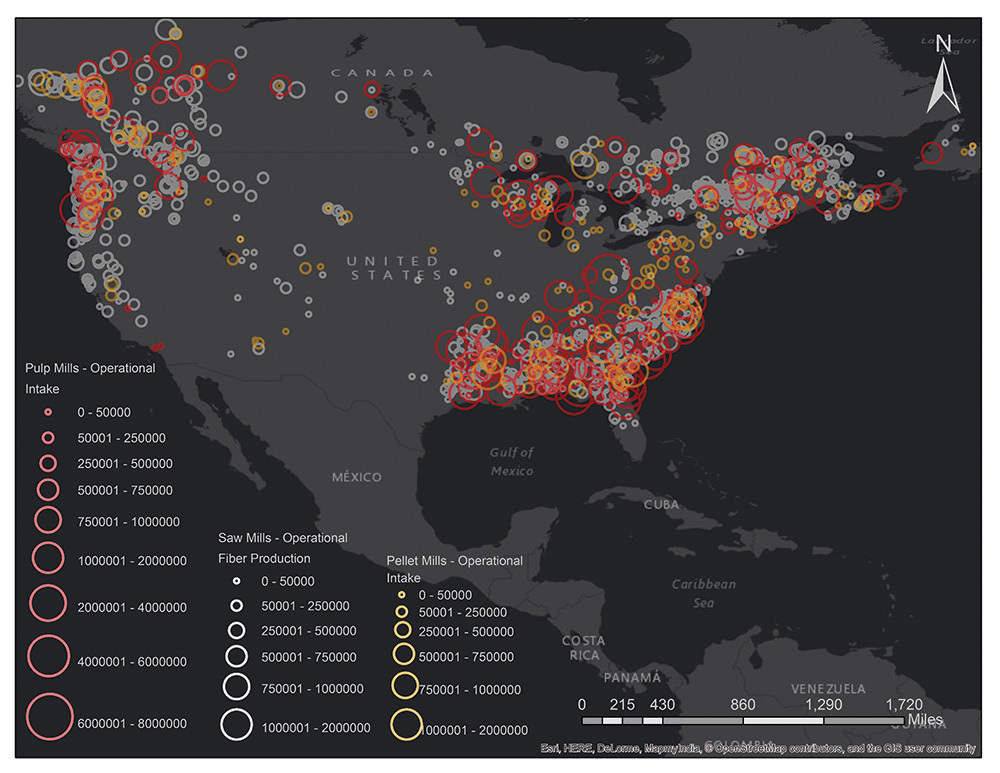

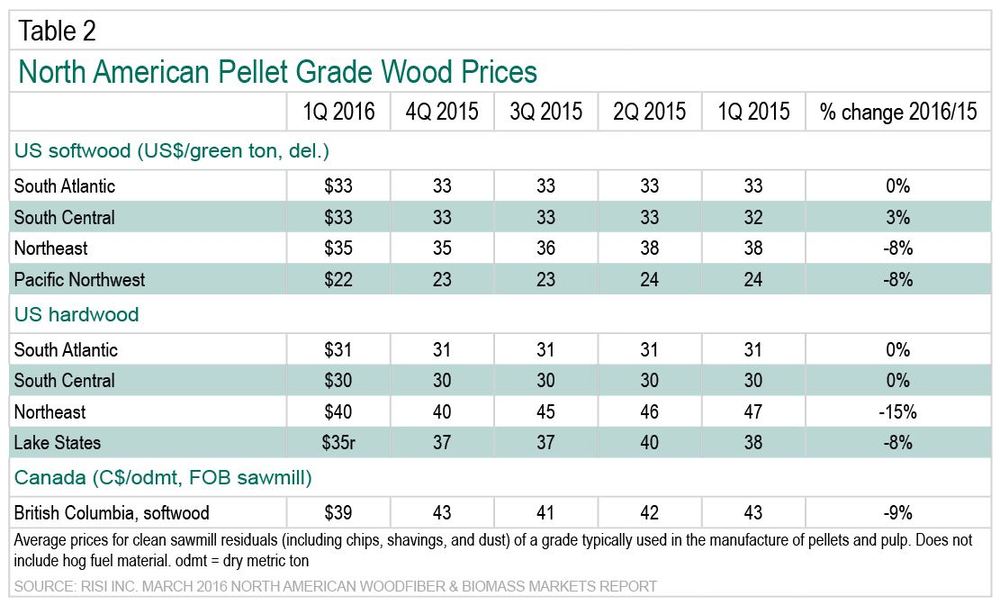

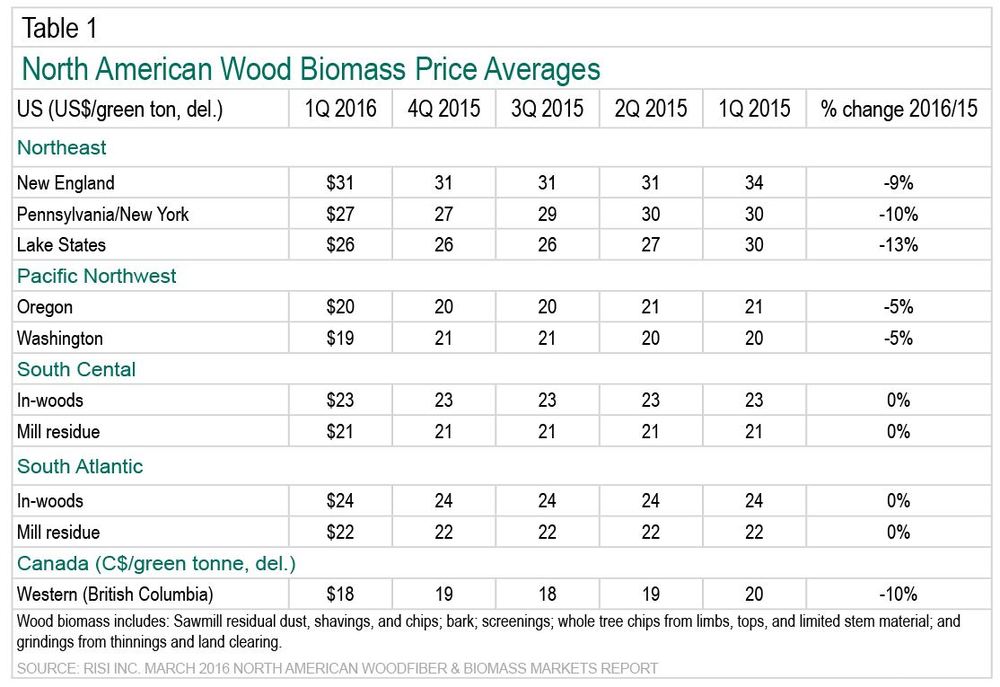

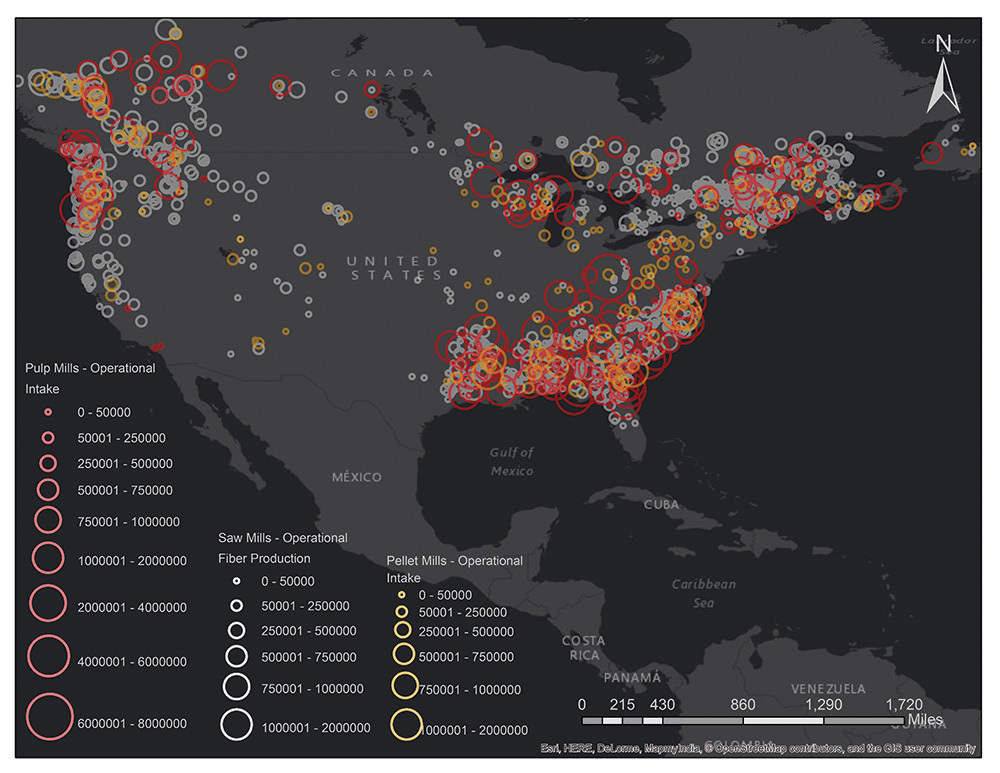

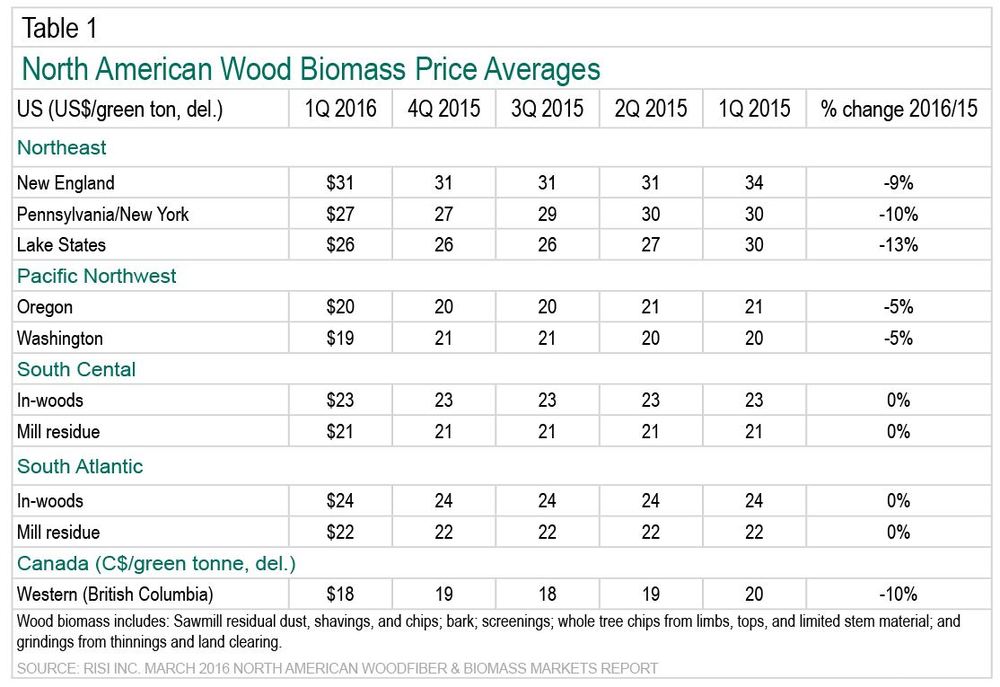

According to RISI’s March North American Woodfiber & Biomass Markets report, nearly every region, with the exception of the South Central and South Atlantic regions, experienced a decline in the average price of wood biomass per delivered green ton from quarter one 2015 to 2016 (Table 1). Overall, there was also a decline or little change in U.S. softwood and hardwood pellet grade prices from quarter one of last year to this year (Table 2).

Different market dynamics exist in the South, with some pellet producers shipping contracted cargoes of pellets to the growing European export market as just one of the reasons it hasn’t been experiencing quite the same pricing trends in its wood fiber and biomass markets. Nevertheless, increased inventory levels throughout the supply chain have put downward pressure on pricing in many regions. As raw material is the single, biggest contributor to pellet price, looking long-term, the decrease in raw material procurement cost could provide the opportunity for producers to make their pellets more cost-competitive. As for the current status of the industry, Morice believes what producers are going through is an anomaly, but will not quickly leave all areas either. “I think many areas will be feeling this for 12 to 24 months,” he says. “The effects of overinventoried and overvalued product with the recent warm winter underuse will take time to filter through. In many areas, the weighted average cost that a plant will have to go through in order to alleviate their overages is going to take time, especially in light of where fossil fuel prices are likely to be for some time.”

Author: Katie Fletcher

Associate Editor, Pellet Mill Magazine

701-738-4920

kfletcher@bbiinternational.com

Upcoming Events