Filling The Gap

January 16, 2023

BY Katie Schroeder

In March 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine, leading to economic and social turmoil throughout Ukraine and across the continent. Many nations in western Europe and across the globe reacted with economic sanctions against Russia, in order to demonstrate their support of Ukraine and admonishment of the attack. While necessary, sanctions have had a major impact on the European economy, including the pellet market. In December, Biomass Magazine checked back in with industry experts on the impacts Russia’s invasion has had on the industry over the past year.

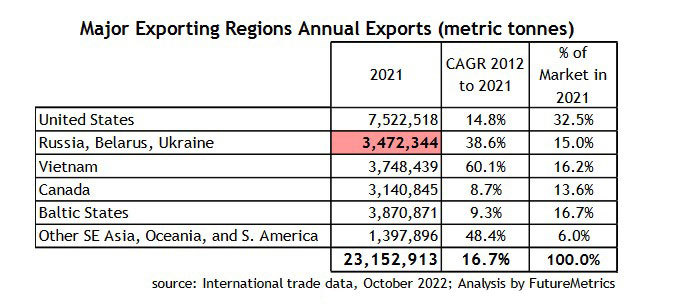

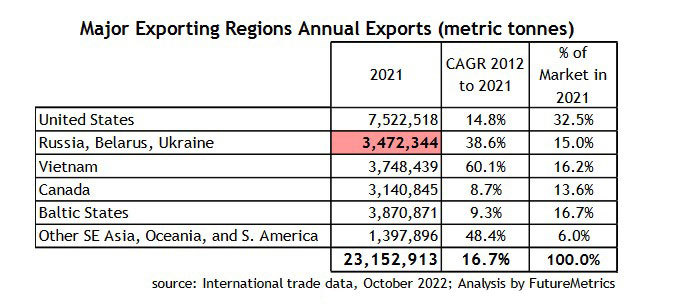

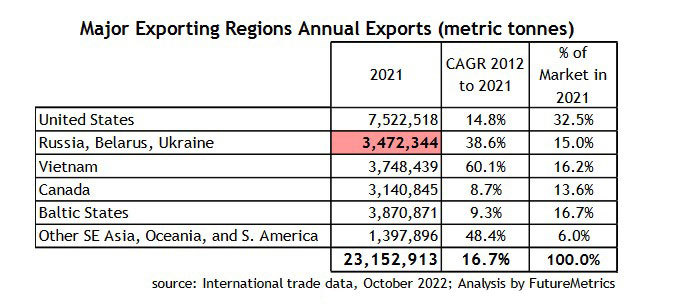

Russia being banned from the market left a 2.5 million to 3-million-metric-ton shortfall, says Tim Portz, executive director of the Pellet Fuels Institute. A few of his members, which include domestic heating pellet manufacturers and other stakeholders across the U.S., have been able to overcome the challenges of exporting overseas, and—at least temporarily—participate in the market. Since last February, the pellet industry has been bracing itself for the worst-case scenario, strategizing to avoid a pellet shortage. “Back to February, European pellet interest started raising concern, because whether it’s in Europe or the U.S., the very worst thing for the pellet industry is to not be able to supply the fuel,” Portz says. “No one wants that. People don’t want that here; people don’t want that in Europe … it gives people a bad feeling about wood pellets. We want people have a good feeling and surety of supply.”

High demand for wood pellets—stemming from a combination of the Russian market exclusion and other sanctions—has pushed prices up drastically, explains William Strauss, president of consultancy firm FutureMetrics. Also catalyzing greater demand is the increase in sales of pellet stoves and boilers throughout Europe, very likely a result of high natural gas prices. Strauss says prices have reached up to over 800 euros ($846) per ton, with a long-term average of between 200 and 220 euros. Prices shifted downward in late November and early December due to warmer-than-normal autumn temperatures, allowing industrial pellet producers to scale back on the quantity of pellets sent to some larger buyers—for example, MGT Teeside and Lynemouth Power Station, both of which are located in the United Kingdom. When operating at capacity, these plants utilize over one million tons of pellets annually. Instead, the pellets unneeded by these operations are flowing into the western European market, helping alleviate the shortage, Strauss explains.

The United Kingdom was one of the countries hardest hit by the loss of Russian pellets, according to Matthew Goodwin, general secretary and standards manager with the U.K. Pellet Council and director of the European Pellet Council. Prior to the invasion, half of the U.K.’s pellet supply was produced locally, while the other half was imported. Approximately 80% of those imports were sourced from Russia, Ukraine or Belarus, a total of 240,000 metric tons. “In the space of one day, we lost 240,000 tons of imports, which, for the U.K. in particular, was a really big issue,” Goodwin says.

In response to the Russian and Belarusian pellet import bar, producers in the U.K. increased pellet production by 5% to 10%. Though not a substantial amount, Goodwin says, that increase and maximization of uptime has helped fill the gap. ENplus pellets from Brazil have also contributed, and another tactic that Goodwin and his colleagues worked on with the U.K. government was a one-year waive of the ENplus certification requirement on wood pellets, which has allowed the sourcing of heating pellets from North America, which are A1 quality but not ENplus certified. With some screening, the market has also been able to use tens of thousands of tons in industrial pellets from Drax. “North America has some great-quality pellets, but there are very few ENplus-certified companies,” Goodwin says. “So, we’ve been able to bring in PFI-certified pellets or even just A1 grade pellets without any certification—as long as we can prove sustainability, then we can use them in the U.K.”

Goodwin explains that the U.K. government was very proactive in working with the U.K. Pellet Council to change the requirements and help compensate for the shortage. Wholesale prices came down from $450 to $350 in late November and early December. “That was a big win with the change of policy that came at a perfect timing,” Goodwin says. “But at the moment, in the U.K., I can’t say we will not have any shortages—it’s very cold here now, and in a month’s time, I might be saying something completely different.”

Portz reaffirms this, explaining that the unknown of how intense the winter will be has made it difficult for suppliers in the U.S. to know whether or not to take the opportunity of selling to the European markets. The economics of exporting for U.S. pellet producers may not work very well for those without ocean-bound access, due to shifting prices and demand. “If all the sudden, the bottom drops out of the thermostat in Europe, everything could change, and in a hurry,” Portz says. “Pellet sales tend to be very fickle, and a cold snap will really excite consumers to action.”

There are several factors that lead U.S. producers to view the European markets as either a risk or an opportunity, Portz says. Some producers don’t want to risk not being able to supply long-time customers by diverting some of their supply to a different market. “You have some producers who say, ‘I do not want to sit on this inventory, it was slow-moving, it didn’t move last year, I’m going to take an opportunity and I’ll take the risk of having to disappoint my domestic retailers,’” Portz says. “And again, other people have decided that they don’t want to do that. Who ends up being right or wrong is yet to be determined, and everything that influences wood pellet production—the strength of the year, our ability to get fuel to everybody who wants it, etcetera—all of it hinges on weather.”

It can be difficult for pellet producers to walk the tightrope of having an adequate supply, but not so much that they are left with considerable inventory post-season. “In the past three years, U.S. sales have ranged anywhere from 1.75 million to 2.2 million—that’s coming up on 500,000 tons, which is in the neighborhood of 25%,” Portz says. “Not many products have demand cycles that are that variable—I would say heating fuel is one of the most variable products out there.”

For U.K. producers, the shortage caused by the removal of Russian pellets from the market has led to a “rebalancing of the industry,” Goodwin explains. Prior to the shortage, the pellet industry was barely profitable for some time, with many companies consolidating, players coming and going, and U.K. pellets being undercut by cheap Russian pellets. “In the U.K., we’ve actually grown over this period—we now have more members for the first time [in] a long time,” he says. “And I think the prices are not going to go back to where they were.” Due to the state of the energy market and the fact that the Russian pellet industry is unlikely to reenter the pellet market for a while—if at all—Goodwin believes now is the best time for people to invest in pellets. “I think once we get past the blip at the moment, pellets are going to be very competitive in the long term, and I think that should give people confidence to invest in producing pellets. It’s very much what we, as the British Pellet Association, want to promote—localized production, because it makes sense,” he says.

Author: Katie Schroeder

Staff Writer, Biomass Magazine

katie.schroeder@bbiinternational.com

Under the Radar

In December, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project published a report indicating some traders are evading European Union sanctions on Russian and Belarusian wood and wood pellets, claiming they are coming from Central Asia. “On paper, the EU’s imports of wood from the two Central Asian states have surged from around 445,000 euros’ worth in 2020 and 2021, to over 30 million euros between June and October 2022 alone, after the sanctions started to be enforced,” the report says. “Yet Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan have few forests—trees cover less than 6% of their terrain—and both stopped exporting most types of wood in late 2021.” The report, part of which focuses specifically on wood pellets, can be accessed at iccrp.org

Advertisement

Advertisement

Upcoming Events