Gearing Up

October 26, 2010

BY Lisa Gibson

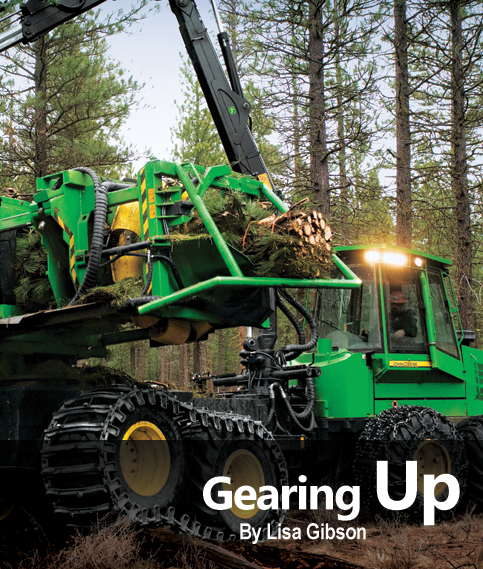

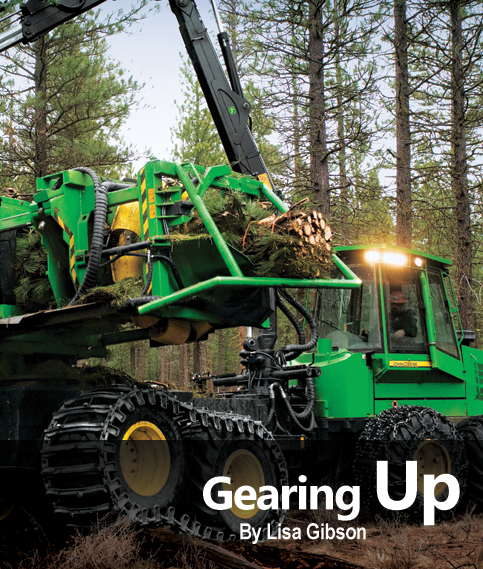

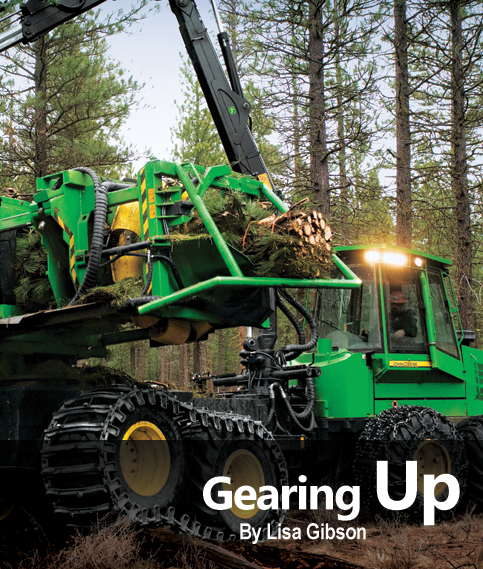

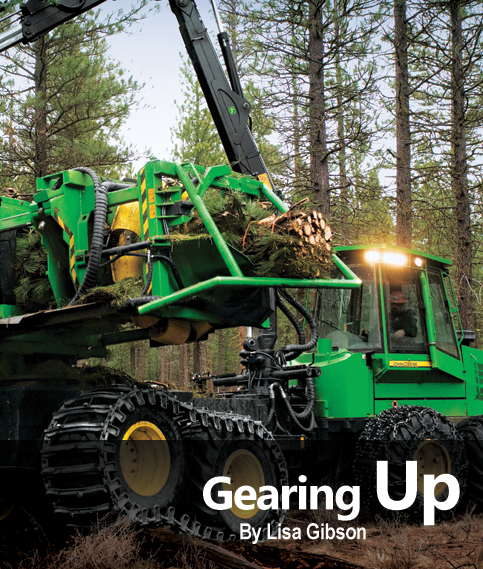

The claw-like mechanism on John Deere’s woody biomass harvester and bundler grabs slash from the forest floor left behind by forestry and logging operations, compresses it by about 80 percent and then wraps and cuts it into slash logs about 10 feet long and 24 to 32 inches in diameter. Despite its size, the giant equipment moves smoothly and seemingly effortlessly through the forest, exerting about the same amount of pressure on the ground as would a walking human being.

The John Deere 1490D Eco III Energy Wood Harvester is one of only a few commercialized machines that have been developed specifically for biomass handling, although many developers of these purpose-built, modified systems say a more robust biomass market would drive sales and spur more development of equipment still stranded in the research phases. From forest biomass to short-rotation, woody crops and herbaceous dedicated energy crops, U.S. markets seem to be lagging behind the European curve, prompting equipment developers to look overseas for models of effective harvesting and handling systems used in Europe’s already-developed biomass markets.

Filling a Need

The 1490D was launched in 2002 in Finland, where forest biomass currently generates about 30 percent of electricity demand and most cities and villages employ wood-fired district heating systems. The machinery was released onto the U.S. market the following year, targeting loggers of both softwood and hardwood. Mike Schmidt, manager of forestry renewables for John Deere, says the equipment was a reaction to a market necessity.

“It was a need,” he says. “In Europe, they’ve been in the renewable energy business for a long time. They needed a better way to collect slash. It’s a very difficult product to collect if you go out into the woods to get it.” Development of the biomass harvester and bundler began in Sweden in the early 90s by a company called Timberjack and transferred to John Deere when it acquired Timberjack in 2000. “John Deere in essence completed the research and development of the machine,” Schmidt says.

The system, a mounted bundler on a forwarder, has the capacity to compress, wrap and cut more than 25 bundles per hour, each weighing between 900 and 1,300 pounds and providing about 1 megawatt hour of energy, according to Schmidt. The extended-reach boom, purpose-designed grapple and ecofriendly design allow it to maneuver around a stand with minimal movement, leaving healthy trees and much of the forest floor untouched. The machine was originally designed to work with traditional forwarders and wheeled harvesters, but when modifying it for U.S. use, John Deere integrated it into U.S. systems, which can vary, Schmidt says. “When you’re talking about biomass harvesting, you’re talking about taking different combinations of traditional machines and integrating them with a machine like this 1490,” he says. “We’ve integrated it into every type of system to make it work around the U.S. and Canada.”

The 1490D is at work in 16 countries and feedback has been positive, but U.S. markets have been slow to develop, Schmidt says. “We’ve got customers who want to buy the machine as soon as they have a market for that material,” he says, adding that markets are beginning to develop more quickly in states with renewable portfolio standards. “Biomass is by far the cheapest of the renewable energy and so you’re seeing more plants scrambling. And they’re having to go out and try to find biomass in untraditional ways, which brings in the bundling because you can haul these bundles on log trucks and can get into areas of the forest where you cannot get the chip vans.”

Schmidt says those vital markets are growing rapidly and that will mean a substantial increase in demand for the biomass harvester. “It’ll spur sales and we’re trying to plan for that rush,” he says.

The expected rush for forest woody biomass harvesting equipment could come any day and many manufacturers are preparing, but economics always have a significant influence. “Somebody just has to decide that it’s economically feasible to go ahead and purchase those machines and put them to work,” says Tom Gallagher, associate professor of forest operations at Auburn University’s School of Forestry and Wildlife Sciences in Alabama. “And at the moment, on the baling and bundling side, it’s marginally economically feasible. On the chipping side, there are plenty of people out there doing it already.” Chipping is economic as long as transport distance isn’t more than about 50 miles, but bundling and baling will need the market to pick up a little bit, he adds.

“I believe we’re just starting with this,” Gallagher says. “As this process and opportunities develop, I think we’ll look to Europe because Europe’s kind of ahead of us with their higher fuel prices and they’re doing some of this already. I think there’s a lot of development that has to take place over here as we apply it to what I consider our existing conditions.” For instance, Europe already has efficient modified harvesters capable of handling short-rotation plantations of willow and poplar, he cites.

Advertisement

Willow and Poplar Chopper

Tim Volk, senior research associate with the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY ESF) in Syracuse, had been bringing in equipment from Europe to harvest his research team’s willow and poplar trees until he got a call from Case New Holland. “They said they could run a forage chopper through our willow,” Volk says. “And we said, ‘By all means, come and do it.’”

The company developed a cutting head for its forage chopper that will cut and chip willow and poplar up to 4 inches in diameter. The forage chopper is traditionally used for corn or grass, but the new cutting head allows the conventional equipment to harvest short rotation woody crops as well. “So the advantage of this machine is that people can use it to harvest agricultural crops during the growing season and then after leaf fall, which is when we harvest, they can change the cutting head on the front of the machine and run it through willow and poplar,” Volk explains.

Much like John Deere, Case New Holland developed its machine after seeing a need in the market, mainly in Europe. “We didn’t invent forage harvesting like this, but we’ve perfected it, if you will,” says Dave Wagner, brand marketing manager for New Holland. While several units have been sold in Europe where the wood chip industry is further along, Wagner says the equipment is still in experimental stages in North America, evaluating the end uses for the material. “The cutting head itself is ready now,” he says. “What we’re missing is really a stream of product to harvest and the ultimate uses of that product.”

The header itself comes with a price tag of about $105,000 and the entire chopping package with a self-propelled harvester runs about $400,000, Wagner says, reiterating Volk’s point that the cutting head can be switched after traditional harvests, allowing for another viable season for use of the forage harvester to help put more hours on it and pay for itself sooner.

A high-quality, salable product pays off, too. “In the past few years, the material we’ve been getting out of this system has been very nice,” Volk assures. “It’s very consistent quality and the chip size fits well within the specifications of all the end users we’ve talked to. So people have generally been very happy with the end product that’s coming out of the machine.” Some coordinating and logistics issues remain, such as how to get the chips off the field fast enough and dump them into trucks, Volk says. His willow harvests have been going to heating plants and combined-heat-and-power plants, as well as coal plants.

For the most part, hybrid poplar and other short-rotation woody energy crops in the U.S. cater to forestry equipment, planted farther apart and harvested only after it reaches a certain size suitable for the heavier-duty forest machinery. Europe, however, has tens of thousands of acres that are harvested using a more efficient modified sugarcane harvester. “Forestry equipment is not efficient for these crops,” Volk says. “You need to modify ag equipment.”

There’s no question that a stronger biomass market in America would drive sales of that modified equipment, Wagner says. “If there were uses for the products that are created this way and there were a source for the raw material … we’re ready to go today,” he says, adding that it would take a few months to build more heads, but that’s just a drop in the bucket in the life cycle of a tree.

Volk thinks the market for Case New Holland’s forage harvester and cutting head will develop with custom operators who will cut others’ wood crops, instead of landowners and loggers using the machinery themselves. It’s just too expensive for every landowner to own one. “Just like not everybody owns a combine or a forage harvester now,” he explains. “They often hire out that work to be done and I think that model will continue.”

Baling Biomass

Advertisement

Stempower Resources, based in St. Joseph, Minn., has experienced a similar lag in machine sales for the Biobaler, developed by Anderson Group in Quebec, Canada. Stempower is marketing the machinery in the upper Midwest, focusing on the area’s thick brush that is too dense for traditional agricultural machinery, but not thick enough to warrant forestry equipment. The Biobaler uses a large cutter drum and is pulled behind a traditional tractor. “It cuts the trees, chips them, throws them into a bale chamber and wraps them into a 4-by-4-foot, roughly half-ton bale,” says Peter Gillitzer, Stempower president and co-founder.

The Biobaler is the only commercial woody biomass baler on the market, Gillitzer says, adding that other brush cutters just shred the material on-site and blow the pieces back onto the ground, but don’t gather it in an efficient way for use. “The main benefit is first you can use an existing tractor,” he emphasizes. “And the second is instead of a chip—where you’re basically locked in at that moisture content and you have to utilize that within three to six months—bales can be stored, inventoried and dried down. You’ll increase the Btu value of it.”

Even with the material drying advantage, selling the machine has proven difficult because a lack of market for the product stands in the way. Gillitzer’s strategy has been to encourage a marriage between the Biobaler and land management, marketing to state and federal agencies and private landowners. “In the long term, I think it’s pretty attractive because it’s going to offer a type of material—small diameter trees and shrubs—that currently there’s no viable way to harvest,” he says.

Volume and Moisture

One major challenge in harvesting dedicated energy crops is the volume of the material in comparison with agricultural crops, according to Sam Jackson, research assistant professor with the Center for Renewable Carbon at the University of Tennessee. “When you start talking particularly about dedicated energy crops, the volume of material of biomass per acre typically is far greater than anything that these folks have encountered in terms of harvesting hay crops, alfalfa crops and things like that,” he says. “So one of the hurdles they’re working to overcome is how do we efficiently handle this volume of biomass that in some cases can be four times what a normal hay field might yield?”

Dedicated energy crops are typically cut and mowed, then baled, while crop residues can be effectively harvested using bales or cob caddies, Jackson says. His team has been working with switchgrass and aims to develop an efficient single-pass harvesting system, with moisture content being the biggest hurdle. The team works with researchers from Genera Energy, a company developed by the university, and received a grant from the U.S. DOE to evaluate in-field chopping of switchgrass to replace baling. The experiment is expected to yield higher operating efficiencies, as the chopped material can be handled in a more automated way than large bales.

Currently, though, the team uses relatively standard machinery. “Typically what we’ve used has been standard hay equipment that is unmodified or has been slightly modified with larger pickup heads or a higher-capacity throughput mower,” Jackson says.

That type of modification will be seen more in the herbaceous energy crop sector, he predicts, as minor modifications can typically make existing equipment suitable for the current scope of dedicated energy crops being harvested in the U.S. “There will be more specialized equipment in the future, but I think as of right now, you’re seeing most of these manufacturers being able to modify existing equipment.”

Those manufacturers are certainly researching and testing new ideas, recognizing the market potential biomass represents. “All in all, I think they’re all fairly bullish on the market opportunity for them, and this investment—in terms of testing equipment, modifying equipment—is something that will pay off in the future for them,” Jackson says.

Author: Lisa Gibson

Associate Editor, Biomass Power & Thermal

(701) 738-4952

lgibson@bbiinternational.com

Upcoming Events