Making the Case for Marine Biofuels

Invalid Date

BY Michael Kass

The maritime industry is one of the most important transportation sectors, with more than 80% of all goods shipped via large container or cargo vessels that are powered using residual heavy fuel oil (HFO). The global economy is, therefore, closely bound to heavy fuel oil and maritime transport. Unlike the automotive industry, this sector has not received much regulatory attention until now. Sulfur reductions in residual fuel oils were imposed by International Maritime Organization starting in 2020, and emission control areas were established in the U.S. and northern Europe to reduce shoreline sulfur and particulate emissions from these vessels. However, maritime transport also accounts for 2-3% of global emissions of CO2, which is significant, especially compared to global aviation. To mitigate marine CO2 emissions, the IMO seeks to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from 2008 levels by 50% in 2050. To meet this challenge, the maritime industry is looking heavily at renewable fuels, including biofuels such as biodiesel, renewable diesel, pyrolysis oils, etc., and zero-carbon fuels like hydrogen and ammonia. Some of these fuels, such as methanol, can be synthesized via several routes, including biomass. Because of the global nature of maritime transport, a multiple-fuel strategy is needed based on regional legislative initiatives, economies and unique bioresources. It’s not a one-size-fits-all approach and will likely mean a higher degree of fuel flexibility than what is currently available. To reduce infrastructure costs and pressure, biofuels have high potential to be used as drop-in candidates for HFO.

Fuels With Low Impact on Port and Shipping Infrastructures

The two most immediate drop-in candidates for HFO are biodiesel and possibly renewable diesel. Biodiesel (derived from vegetable oil or waste cooking oil) is the most studied at this point for several reasons, including that it is available in suitable quantities for full-scale field trials, and it shows excellent blend stability with HFO (biofuels are evaluated primarily as blends with HFO). Blending with HFO is important, since there is not enough biodiesel currently available to run as a neat fuel for marine shipping. Also, the engine and shipping companies are taking a measured approach to gain a solid understanding of performance before moving to higher blend levels. The U.S. DOE’s Bioenergy Technologies Office is also exploring fast-pyrolysis (FP) and hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) oils, which are collectively referred to as biointermediates, and produced from a large variety of feedstocks. These oils must be heavily upgraded in order to be a distillate drop-in. However, because the large two-stroke crosshead engines used to power the large cargo and container vessels can operate on lower combustion quality fuels, the level of upgrading (and hence cost) necessary to produce a suitable fuel is expected to be lower. Biointermediates are being evaluated at four DOE labs (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and Argonne National Lab) for suitability as a marine fuel. Oak Ridge National Laboratory has been primarily concerned with addressing the technical issues associated with fuel and infrastructure compatibility.

The Barriers

Barriers can be broken down by technical feasibility, cost and availability. Availability and cost are the most daunting. Biofuel production will have to be scaled up considerably to meet the demand by the maritime sector, and the low cost of residual fuel oils precludes biofuel use at this time. Key technical barriers (assuming that blends with HFO are being considered) are blend stability and compatibility with infrastructure materials. Blend stability refers to the propensity of a fuel mixture to cause the asphaltene fraction of HFO to precipitate out of solution, resulting in clogging and plugging issues. This phenomenon is not completely understood and is a major concern when bunkering new fuels onboard a ship. Biodiesel blends exceptionally well with residual fuel oils, whereas conventional diesel does not. As for renewable diesel, it shows a more mixed response to asphaltene precipitation. Raw biointermediates have not shown consistent suitability to be reliably blended with HFO; however, our studies have shown that moderate upgrading (hydrotreating and oxygenate removal) improves blend stability. Aging is another hurdle, but not one we have looked at in high detail. The second hurdle with regard to infrastructure is compatibility. Biodiesel and its blends with HFO are not expected to have serious incompatibilities with metal infrastructure components, but it would not be surprising if some seals and gaskets have to be replaced. A more serious issue is the high acidity of pyrolysis oils. Oak Ridge National Laboratory has performed studies that have shown that corrosion is not a concern for fuel system metals when blend levels with pyrolysis oils are kept below 50%.

Advertisement

Advertisement

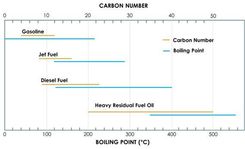

Competition With Sustainable Aviation Fuel

Currently, a key concern is the availability of biomass for fuel production. Sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) is expected to be a large consumer of biomass. Incentives have been established for the production and use of SAF for the aviation industry, but there are none in place for the maritime sector. The maritime community is rightly concerned that most biomass production will be directed toward SAF. Assessing the level of competition with SAF is an area of high interest for the DOE multi-lab team, but we are also looking at mutual benefits, too. As can be seen in Figure 1, the compositional range of jet fuel is markedly different than that of HFO used to power large ocean-going vessels. A key feature of biointermediates is that they have a wide compositional range that includes the nonoverlapping ranges of SAF and marine HFO. The lighter hydrocarbon fraction of biointermediates can be more economically synthesized into SAF than the heavy portion, which by its very nature may be more suitable (and more cost effective) for use as a marine fuel. This complimentary scenario presents a welcome opportunity to advancing biomass for both SAF and marine biofuels.

Biofuels as Pilot Fuels for Zero-Carbon Fuels

It is important to keep in mind that marine engines being developed for zero-carbon fuels require pilot ignition to ignite the main charge. Pilot ignition is currently done for methanol and liquified natural gas-fueled ships using a diesel-like distillate having a high cetane number. These pilot fuels can be up to 5-10% of the total fuel use (which is around 300 million metric tons per year). Therefore, in order to further reduce carbon intensity, biofuels—especially biodiesel and renewable diesel—are heavily being considered for pilot use. Even so, it is important to keep in mind that if the existing HFO-fueled cargo fleet could be converted to methanol overnight, annual production of at least 15 million metric tons of biodiesel or renewable diesel would still be needed. This quantity is over 50 times the volume of biofuel produced each year. As a result, biofuel production would have to be scaled up to meet this demand, even after the industry transitions to zero-carbon fuel options.

Author: Michael Kass

Engineer and Researcher

Fuels, Engines Emissions Research Center

Oak Ridge National Laboratory

kassmd@ornl.gov

Advertisement

Advertisement

Upcoming Events