Streamlining Downstream Delivery

PHOTO: BRYAN SIMS, BBI INTERNATIONAL

September 8, 2011

BY Bryan Sims

Economically, the prospect of producing biodiesel on a small or community scale certainly comes with its challenges. Aside from producing biodiesel, however, producers are faced with unpredictable swings in feedstock price and availability as well as fees associated with equipment maintenance, transportation, administration, permitting and numerous other ancillary expenses. Not only can upstream and midstream costs cut into the bottom line of a small producer, but downstream costs can equally make or break an operation if an effective distribution model isn’t in place to support growth and development of the business. Because the operation is demand-driven, an increasing number of small-scale biodiesel producers have employed, or are at least considering, unique distribution approaches that allow for speedy, cost-effective delivery of B100 bulk or blended product to customers—sometimes without relying on brokers or distributors. Failing to control or at least possess some ownership of downstream distribution of product could translate into biodiesel producers being at the mercy of the feedstock suppliers.

Typically, biodiesel is picked up at a facility by a distribution company, blended at a rack with a computerized system, and then brokered and distributed to local retail fueling stations where pockets of supply might be limited. When biodiesel is not offered at a rack, fuel distributors that want to offer it typically splash blend it themselves and maintain their own storage equipment.

While rack blending biodiesel might offer significant benefits to fuel distributors and potential consumers because of the $1-per-gallon blenders tax credit in place, effectively employing the direct sales approach might carry with it several advantages, depending on a producer’s resources and cash flow situation, according to Todd Hill, president and founder of Promethean Biofuels Co-op Corp., a 2.1 MMgy biodiesel facility in Temecula, Calif., that uses waste vegetable oil as feedstock. While Promethean Biofuels is currently relying on distributors to get its biodiesel out to customers, Hill says he would like to employ the direct sales approach.

One of the biggest advantages about the idea of a direct marketing approach for blended product or B100, according to Hill, is that it can accelerate a producer’s ability to get product out more rapidly to generate revenue. Additionally, direct distribution, he adds, also allows a producer to customize the scale of transactions and the type of customer interaction much better than if a producer relied on distributors.

“I think that it’s actually more important for a small producer to go direct than a large producer, because a small producer is going to take longer to build up critical mass,” Hill tells Biodiesel Magazine. “It just takes longer to do that. It also gives you that ability to call your local mayor to get people who will come and they’re going to have a relationship with you and it might get you a little bit more margin in the end. A relationship is an opportunity to build a brand.”

Some producers, like Midlands Biofuels LLC, a 300,000-gallon-per-year biodiesel plant in Winnsboro, S.C., prefer to work with third-party distributors to deliver their blended fuel to municipalities and small businesses. In addition to relying on distributors, however, Midlands Biofuels also offers B100 on-site where customers can fill their tanks. While relying on distributors might be considered burdensome for some, co-founder Brandon Spence finds that working with a distributor allows his company to focus strictly on biodiesel production while it streamlines the billing process.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“Another advantage of working with a local distributor for us,” Spence says, “is that we get on a good production schedule. Our production schedule is based on a predetermined amount that’s usually on a weekly basis.”

According to Hill, a direct distribution approach could be an advantageous proposition for those who are, or are considering, delving into blending biodiesel with diesel fuel in order to monetize RINs and other state incentives. Doing so, he says, might give a producer more ownership of the end product rather than passing on the incentive to the blender at a rack or distribution terminal.

“If you want to commoditize your RINs, that is not a B99 solution—that’s a B80 solution,” Hill says, cautioning that small producers should evaluate appropriate administrative resources, personnel and funding in order to maintain accurate RFS2 reporting requirements before considering a direct sales approach for blended product. “From that perspective, you also need to perhaps have some metering equipment, depending on where you are, to make sure you can guarantee that when you say it’s B80, it really is B80. Regardless, you still need to have a process in place that allows you to say that you’re delivering a known quantity of biodiesel into a known quantity of diesel fuel and that there’s reasonable assurance that we’ve got good mixing. You’ve got to keep that inventory separately.”

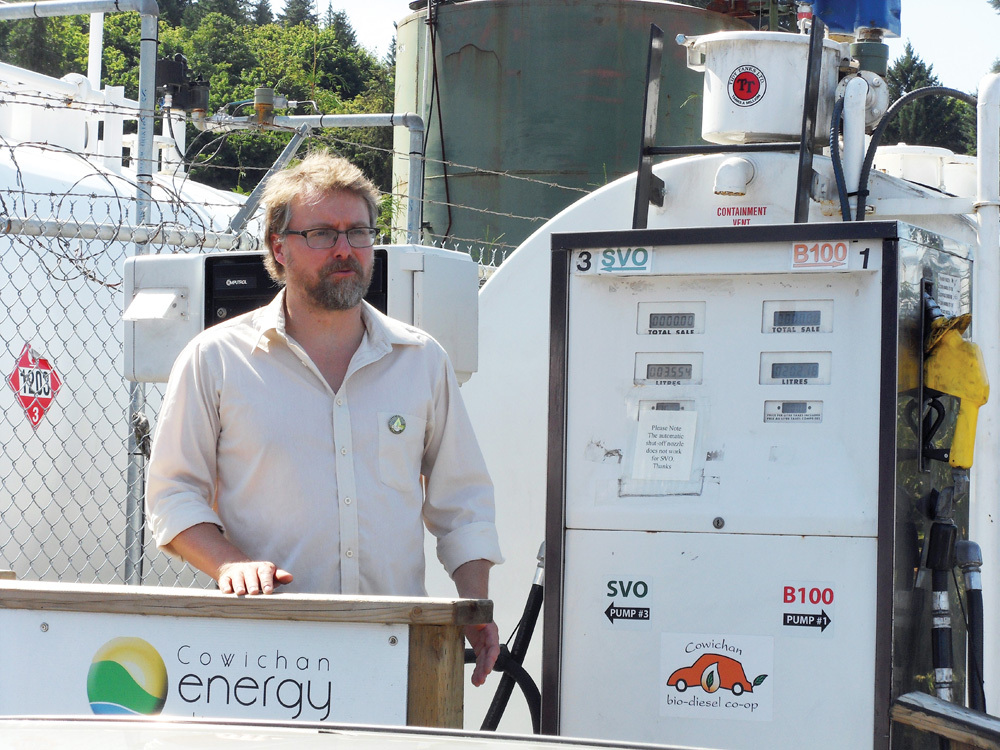

For producers like Cowichan Bio-Diesel Co-op, a member-owned small-scale producer located in Duncan, Vancouver Island, British Columbia, deciding on the best model to market and distribute biodiesel from its 365,000-liter-per-year (96,000-gallon-per-year) production facility was never a question, according to President Brian Roberts. For six years, the member cooperative, which officially started up its Bing’s Creek Biofuels Facility on the site of the Cowichan Valley Regional District Solid Waste Management facility in July, had been supplying biodiesel from waste vegetable oil to its members in jugs through local farmers’ markets. In response to increased demand for biodiesel, the company now offers B100 to its members at a cardlock fuel pump. Cowichan Bio-Diesel sold about 5,000 liters at the cardlock pump since it opened in November 2010, and “we could’ve sold more,” says Roberts. While selling biodiesel directly to its member-customers was a necessary—and not an optional—approach for Cowichan Bio-Diesel, Roberts says that it serves as a springboard for expanding customer relationships outside its core members.

“The cardlock itself is probably a more expensive option because we’re focused on trying to distribute to a number of smaller consumers of the product,” Roberts says, “but now that we’re growing, we’re starting to look at fleets more and they’re starting to approach us.” He adds that the barrier for biodiesel entering a given community or municipality is much less when selling direct compared to relying on distributors to supply its customer base.

“A direct marketed community cooperative is a really good vehicle for being able to develop something like what we have,” Roberts adds. “It kind of provides a neat cocoon to work within and it’s kind of a little forgiving along the way.”

Straight from the Factory

Advertisement

Advertisement

Sirona Fuels, a 1.5 MMgy plant in Oakland, Calif., is offering B99 to its customers straight out of pumps installed on the premises of its production facility. It’s a model that’s working after previously relying on selling biodiesel to distributors and retailers for two years, according to President Paul Lacourciere. By selling biodiesel direct, Lacourciere says he’s been able to offer biodiesel cheaper than what’s being sold at a regular retail station. Employing this approach, he adds, mitigates the core pressure points that come with incoming feedstock costs and fluctuating diesel prices downstream. Lacourciere says Sirona Fuels monetizes RINs and also began monetizing California Low Carbon Fuel credits.

“I’ve saved my customers anywhere from $500 to $5,000 a month,” Lacourciere says, adding that his company was able to sell 1,000 gallons to new customers in just the first 10 days of offering biodiesel at its plant.

“That’s a huge win for my customers,” he says, “and that’s a huge win for the environment because they’re going over to an environmentally friendly fuel—and that’s a win for me because I can get a price that’s at least reasonably profitable, at least for making margin, and [I can] stay in business that way.”

Like many small-scale producers, the challenge is to maintain equilibrium when it comes to supply of biodiesel relative to demand for customers. While Sirona Fuels is capable of producing 80,000 to 100,000 gallons each month, demand is outstripping supply, according to Lacourciere,

“I’ve got orders for probably more than 20,000 gallons of fuel that I can’t supply,” he says.

While local biodiesel production may carry with it inherent benefits in avoiding transportation costs, selling direct from the production facility, Lacourciere says, has enabled his company to improve the margin while selling biodiesel for significantly less compared to what it would otherwise be priced at a retail station.

“My retail price of biodiesel tends to run anywhere from 10 cents to 70 cents below diesel prices,” Lacourciere says, adding that selling blended biodiesel straight from the site of the production plant could, or should, become more commonplace in the industry.

“From a business model standpoint, I actually think it’s the best way to go because by putting distributed energy production facilities in your community, you keep more dollars in your community,” Lacourciere says. “The margins are better for the local producer, and the prices are better for the suppliers and for the fuel customers. By having local production, we keep more money in the community and everyone can be enriched by that.”

Author: Bryan Sims

Associate Editor, Biodiesel Magazine

(701) 738-4974

bsims@bbiinternational.com

Upcoming Events