Studying Switchgrass

PHOTO: CERES INC.

October 26, 2010

BY Anna Austin

Biomass utilization isn't the only way to meet rising energy demand and decrease fossil fuel use, but it will play an important role in the future of renewable energy.

This perennial grass has only been studied as an energy source the past 30 years or so, but compared with centuries-old corn and soybeans, switchgrass has the potential to be an important crop, especially in the Southern U.S.

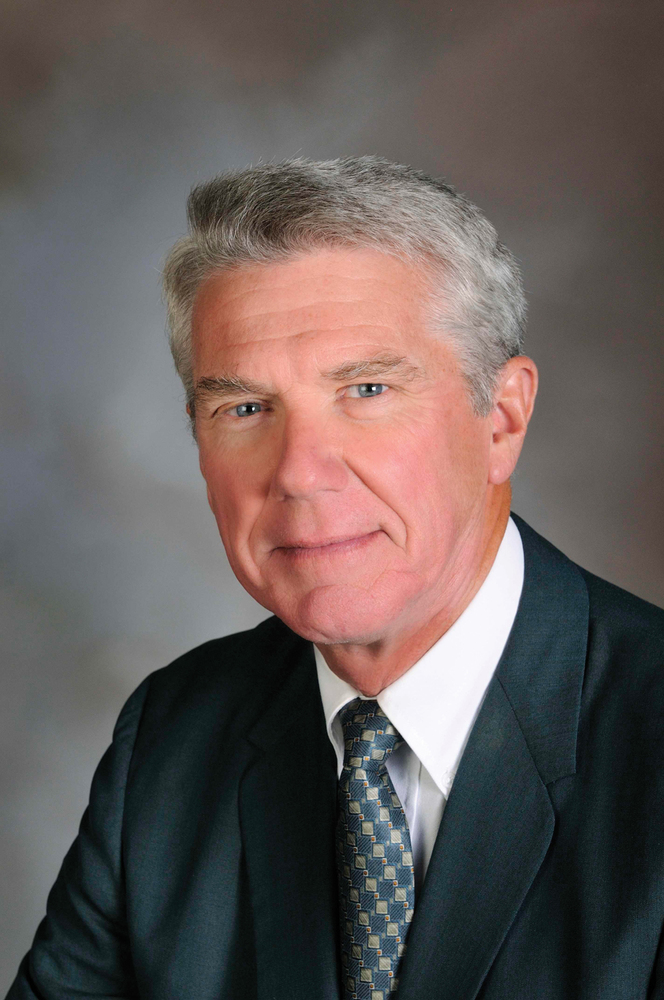

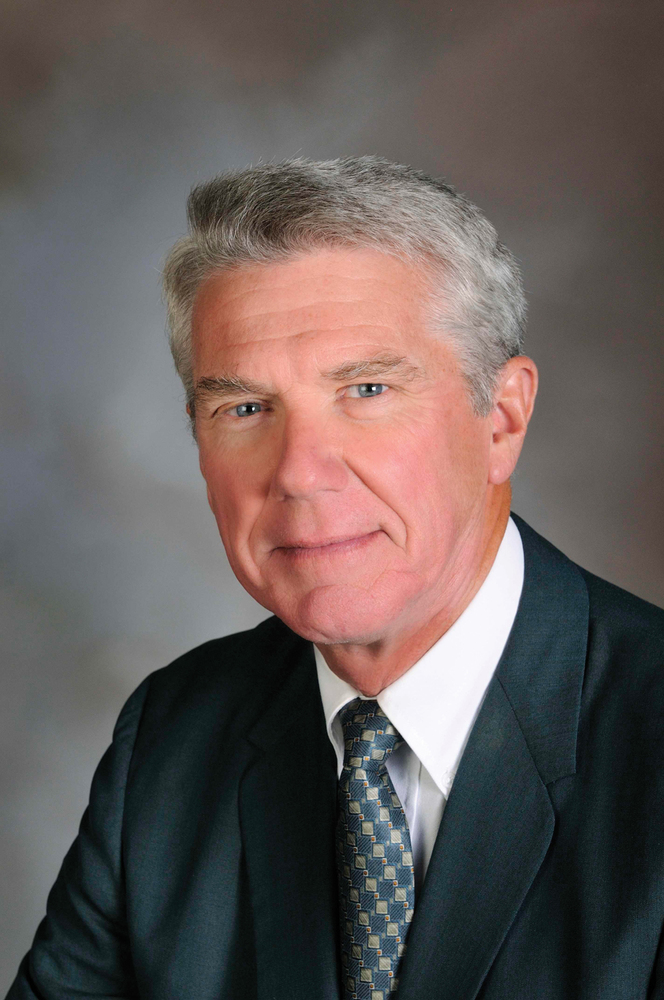

David Parrish, a retired agronomist and professor at Virginia Tech, where he says the story of switchgrass began, says switchgrass is a good candidate for a dedicated energy crop for electricity or biofuel production but advancements need to be made.

Parrish has studied the establishment and management of switchgrass for more than 30 years, and took part in the U.S. DOE’s initial research project to study switchgrass as an energy crop.

One of the first steps to growing switchgrass is selecting an appropriate variety, Parrish says.

Choosing a Variety

Switchgrass is generally categorized into upland and lowland varieties, but Parrish says the title of each has little relevance to where they are and can be grown. “The titles imply that the lowlands are found in river bottoms and uplands are found in drier areas, but that’s not necessarily the case,” he says. “Lowland types may be found in drier sites and can be productive there as well. A better generalization for them is that the lowland types are southern/southeastern and the upland types are more northern.” Lowland varieties are not hardy and wouldn’t survive well in harsh weather conditions found in the northern U.S., Parrish adds.

Once a variety is chosen, the next step is to get the crop established.

Establishment Issues

Switchgrass has three main establishment enemies—weeds, dry ground and seed dormancy, which is commonly considered the biggest hurdle.

“If you harvest switchgrass seed directly from the plant and plant that seed, it won’t grow,” Parrish says. Ninety-five percent of switchgrass seed will not germinate. “If you look at the seed tag information on the bag, it will report that the seeds are 80 to 90 percent germinable. That’s true, but those tests are done when they’ve performed a procedure that breaks the dormancy.”

Advertisement

So how do you get the seeds to germinate? There are a couple of ways to do that on a commercial scale, the first is a biological process called after ripening. “If you just leave it for a couple of years, [its dormancy] disappears,” Parrish says. “It naturally becomes more germinable over time. That won’t work from the seed salesman’s standpoint because he wants to sell it, but the grower can plan two or three years ahead of time and hold on to the seed until it’s ready to germinate in a few years.”

The other way to break dormancy is a process called stratification, where seed is moistened and exposed to a cool environment. This mimics what happens in nature when seeds fall from the plants and onto the ground during winter and when spring approaches, they are ready to germinate.

This can be done with a 100-pound bag of seed by dropping it into a garbage can full of water, letting the seed soak up the water, pulling it out and letting most of the water drain off, according to Parrish. The bag should then be enclosed in a plastic bag to retain moisture, placed in a refrigerator and stored at 40 to 50 degrees Fahrenheit for a month.

“The real problem comes when you take the seed out of the cool temperature, because now it is ready to germinate so the seed has to be dried very quickly,” he says. Spreading the seed out and drying it with fans is a quick solution. It is extra work, but it could be the difference between success and failure in establishment, or having to buy 20 times more seed, if only 5 percent is germinable, Parrish says.

The cost of seed varies, mainly depending on whether it is an upland or lowland variety, says Frank Hardimon, certified crop adviser and director of sales at Ceres/Blade Energy Crops. “A good lowland variety will vary, but for seeding cost per acre, generally it will be about $100 to $120 per acre, depending on the amount of pure live seed that you are putting on,” he says.

Parrish says if demand for switchgrass suddenly goes up, as it did during the 1980s in response to the USDA’s Conservation Reserve Program, farmers will want to get by with as little seed as they can because prices will go up. “There are almost a quarter million seeds in a pound, so if you get every one of them to germinate, you’ll have plenty of switchgrass just planting a couple of pounds per acre,” he says.

Perennial grasses are typically slow to establish, says Chuck West, an agronomist/forage and biomass physiology and ecology professor at the University of Arkansas-Fayetteville. “Annual crops establish quickly because they have to; they only have one growing season to complete their life cycle,” he says. “Switchgrass seeds are very small—small packets of energy that provide for seedling growth—and the smaller it is, the less energy it has.”

Unlike switchgrass, which is slow to germinate and emerge, the weeds that grow amongst it are mostly annuals and are genetically programmed to germinate fast and take over. Parrish recommends spraying the whole field to kill off existing vegetation or burning it off, if there is enough crop residue to sustain a fire, a month or so before planting. “Then plant into that killed and burned stubble,” he says. “There will be some that escape—perennial weeds that germinate and come up after the spray—so a second shot at planting time to catch emerging weeds should level the playing field.”

Harvesting and Yields

In Virginia, Parrish says he has seen the best success when switchgrass was planted in about the third week of June. “We’ve found it’s best to wait and plant after the soil is fully warm, but also being mindful of weeds germinating during that time.”

Of course, planting late means harvesting will be late. “If you harvest late, after it goes through that natural die-back, then you’ve got a better quality biomass—it’s lower in nitrogen content and already dry, so a farmer can cut it and bale it in the same day,” Parrish says. When using the grass for pyrolysis, gasification or biochemical processes, nitrogen can negatively impact the quality, Parrish says. Because the nitrogen stays in the soil, farmers don’t have to add more nitrogen into the soil.

While a farmer may not initially notice the advantage of harvesting switchgrass late, it will become more apparent over time. “If you wait until September to November to harvest, you’re going lose about 10 percent of your yield, but that’s only for one year,” Parrish says. “If you look at it over multiple years, you’ll find that harvesting before the die-back has occurred will reduce yields in the next year because the plant is weakened.”

Advertisement

On good soil in the South, a realistic target is 8 to 10 tons per acre, according to West. In some southern locations with poorer soil—rocky, sloping or sandy—yields will be in the 5 to 7 ton per acre range. “During the first year, if you can get your switchgrass plots to about knee high in September, that’s great,” he says. “If you can get it waist high, that’s phenomenal. You’ve got a fantastic stand if you have one plant for every 2 square feet.”

Growers should consider the concepts of switchgrass establishment and growth or yield separately because at the end of the first year the plants may not even be worth harvesting, but the establishment could still be excellent, West says. “It’s really getting the plants to come up and survive all that weed pressure. Once you’re over the one- to 1½-year establishment barrier, switchgrass may be there for 10 to 15 years, so annual costs become minimal.

While interest in planting switchgrass is growing, its growth rate hinges on one factor—demand. “If there was a market for switchgrass, more farmers would probably grow it,” Parrish says.

Market-Driven Interest

Establishing a market for the crop involves getting farmers to do something out of their comfort zone and building facilities to use the crop.

“Based on my observations and conversations, [energy crops haven’t] really caught on with farmers at-large,” Parrish says. He believes that has much to do with some farmers being set in traditional ways of doing things. “Many aren’t ready to try something new, and like what already works.”

In Arkansas, nobody is jumping into it because there are no buyers for the biomass. West says. “Farmers aren’t likely to grow a new crop unless they’re sure there’s an end market—meaning a contract with an end-user,” Hardimon adds. “It could even be an export opportunity; they just want the economics to work out.”

Hardimon provides support between biorefineries or utilities interested in biopower applications and farmers who want to grow energy crops for them. He’s been involved in growing switchgrass for a Genera Energy, DuPont Danisco Cellulosic Ethanol and University of Tennessee project, and says this spring he supervised the planting of more than 1,000 acres of switchgrass, which are faring well.

Part of Hardimon’s work involves holding educational meetings for farmers interested in growing switchgrass and other energy crops to discuss soil preparation, correct seed planting depth and what problems may emerge. “When a project is getting off the ground, these grower meetings are critical to set expectations for the project,” he says.

Parrish, West and Hardimon all agree that if the Biomass Crop Assistance Program is adequately revised and running again, it would help get things moving. “It will help alleviate some of the costs and risks of establishment and make it more attractive,” West says. “Even then though, there is no big biomass user or power plant that I know of in or near Arkansas using biomass. When a user does get established here, the word will go out that they’re looking for producers and that might change. We have a lot of land in Arkansas that switchgrass would do very well on—better than row crops—some of which has been abandoned or underutilized.”

BCAP will help, Hardimon says, but the U.S. also needs to focus more on renewable energy and provide funds to build qualified conversion facilities, which will be tied to growing the crops.

Switchgrass is not an established crop so there is still much to learn about it, Parrish says “Some varieties have been improved, but it’s still very much a wild species,” he says. “When we do fully understand its biology and needs, it will serve us well; it’s just going to take some time.”

Author: Anna Austin

Associate Editor, Biomass Power & Thermal

(701) 738-4968

aaustin@bbiinternational.com

Upcoming Events