The Great Biomass Inquisition

January 4, 2007

BY Ron Kotrba

Methods to collect agricultural residues already exist. A 2002 American Society for Agricultural Engineers (ASAE) paper indicates that, at the time of the study, less than 10 percent of all the corn stover produced in the United States was being harvested, for use in livestock operations mostly. Horses and other livestock, however, don't put the extreme demand on supply chains like the ongoing biomass inquisition is expected to produce.

Several competing methods to get the oftentimes airy crop materials condensed are under investigation right now, and this doesn't necessarily involve making dense bales for transport. While some researchers are studying baling trials, others are compelled by a more mysterious pathway. Whatever the means of getting the desired materials from the source of origination to its final destination, the methods have to be cost-effective and capable of handling high volumes of materials in an efficient and not so labor-intensive fashion. Different approaches to processing materials on or near the harvest site, which are unconventional compared with baling and hauling, are also undergoing scrutinizing review.

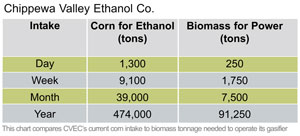

If custom-harvest baling is the preferred method, those footing the bill are faced with the hulking consideration that hundreds of tons of biomass are needed daily to power or supply feedstock to one mid-sized refinery. To put this in perspective, a 1,000-pound horse can eat 50 pounds a day. At that rate of consumption, it would take approximately 10,000 horses to eat all of the biomass needed for gasification to power one 40 MMgy plant—for just one day. Therefore, the implements and practices that farmers already use to harvest biomaterials aren't big enough to handle the large-scale demands that would be placed on infrastructures as biomass becomes more widely used.

Frontline BioEnergy and Chippewa Valley Ethanol Co. (CVEC) are jointly working on a multiphase biomass gasification project in Benson, Minn. The partners were in the midst of early baling trials while earthwork ensued in early November to lay the foundation for a phase one, pilot-sized gasifier. CVEC General Manager Bill Lee talked with EPM about what "state-of-the-art" means when it comes to baling biomass. "At Chippewa Valley Ethanol, we don't have a lot of direct knowledge or history here for biomass collection outside of the collective traditional harvesting techniques that our farmer-owners currently do in terms of baling wheat straw or baling corn stover," he says. "So there's that type of knowledge, and, when you dig into it, that is the ‘state-of-the-art.' There are people who have done work and developed alternatives to that, but so far the practice has not evolved very much beyond that. Simple baling techniques—round bales or square bales." Three cornerstones of CVEC's biomass gasification program are economics, reliability and sustainability. "That's a lot to do, and I think anybody doing work in this area should have the same goals," Lee says.

The gathering of corn stover in quantities suitable for applications like this isn't so cut-and-dry. "Dry collection of stover is risky when you leave it in the field," says James Hettenhaus, consultant and co-founder of CEA Inc., a consulting firm currently working on a three-year, three-phase, $3-million U.S. DOE-funded project with Imperial Young Farmers & Ranchers in Imperial, Neb. "For collection of stover, the window period is short," Hettenhaus says. "If there's a rainy harvest, you might as well forget about it." Also, the longer the wet material is left in the field, there's more of a chance for microbes to eat away at the hemicellulose, he says.

Not only is there a short window to effectively collect the biomaterials, but the moisture of the biomass also has to be taken into consideration. "You need to have the baled material below 20 percent moisture to be stable—or above 60 percent," Hettenhaus tells EPM. "In between 20 [percent] and 60 percent, the stover heats up and turns black, becoming capable of spontaneous combustion."

Another area of concern is that, while gathering the crop residues, unwanted "foreign" substances—rocks, dirt, silt, clay—may become incorporated into the bales. "It would be nice if the stover didn't hit the ground," says John Reardon, Frontline BioEnergy research and development manager. "If you could do it in one pass and get grain in one truck and biomass stover in another, and scatter some of it on the field—obviously you're going to want to leave some on the field—that would be nice."

Whether a farmer practices till or no-till cropping also comes into play. A no-till farmer isn't going to make more than one or two passes over his field to harvest grain or beans and their respective biomass counterparts because it causes soil compaction. "If you're not tilling, compaction is bad," Hettenhaus says. For northern areas, where the short growing season and cold weather make no-till farming impractical, multiple passes aren't looked upon with favor either. Sweet corn and seed corn harvesters, for instance, pluck the ears of corn off of the stalks that remain in the field. "Multiple passes can create a loss of materials by knocking those stalks down," Hettenhaus says.

Off-Site Preprocessing

The bottom line is that much time, effort and money are being invested in building better baling systems. "There are a lot of people interested in moving in this direction, and I think different people will take different approaches," Lee says.

Hettenhaus says the sugar platform is one to look at as it effectively stores bagasse, the term for remnant fibrous plant material left over after sugarcane processing. Rather than harvesting crop residue like corn stover with moisture levels below 20 percent or above 60 percent, the stover would be collected at 50 percent moisture, piled and then saturated with water. "All sugar companies store bagasse wet," Hettenhaus says. "Saturating [corn stover] removes the solubles to go back into the field. When you take the solids out, it's like getting Coke with no ice." Tests have been run on converting this substrate to ethanol. "The pH is 4.1, which is good and will process better." Nearing press time, more results were expected. Taking into account the high water concentrations, Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway is helping examine how to stage it at the elevator in 100-ton railcars.

The treatment of biomass materials needs to be different, depending on the end-use application for which the organic material is destined. The collection and treatment of stover, whose end purpose will serve as energy in combustion or gasification for process heat and steam, for instance, may require different steps compared with stover destined as feedstock. When that material is intended to be fermented into ethanol, reducing it down to a concentrated mix of C5 and C6 sugars in the field will lessen the burden of loading and transporting the cumbersome stalks.

"One scheme is to go through an extrusion operation," Hettenhaus suggests. During such a process, the hemicellulose would come off, the lignin would be made soluble and the glucose sugars from the cellulose would become available. "So rather than taking all that biomass into the plant, just bring in the mix of C5 and C6 sugars," he says. Collection sites could be similar to sugar beet piles, where farmers drive in, have their truck weighed, dump their beets, are given their dirt back, and then are reweighed to adjust for the dirt content. Temporary or permanent preprocessing facilities could be located at the collection site, where such an extrusion treatment could take place. "Preprocessing is a way to meet economic targets," Hettenhaus says. "Also, it is a way to keep farmers in the value chain. How many farmers are going to own one of these cellulosic ethanol plants when they cost several hundred million dollars? None." However, if farmer-owned preprocessing outfits exist at the site of biomass collection perhaps positioned every 15 to 20 miles then the concentrated sugar stock could be economically transported to nearby ethanol refineries where little changes to existing equipment would be needed.

Maybe in the future, harvesters that process while collection is taking place will be invented. Maybe the truck running alongside the combine could be replaced with a mobile preprocessing unit to further simplify the gathering and hauling. Chevron Technology Ventures, a subsidiary of Chevron Corp. now aligned with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in a five-year research arrangement, will be investigating mobile pyrolysis units to accomplish ambitious research and development goals (see Industry feature on page 78 for more information).

John Deere's Slash Bundler

While researchers with John Deere & Co.'s research and development division couldn't offer any comment on early-stage implements for biomass collection that may be under development, those same researchers were quick to point toward the company's already developed, yet limitedly available 1490D Energy Wood Harvester—a.k.a. the Slash Bundler. The bundler is a large piece of forestry equipment that efficiently gathers and compresses debris from logging operations. "The bundler has been used in Europe for years," says Greg Freeland, a forestry applications specialist with John Deere. "In the U.S., we're 50 years behind [Europeans] in forest management."

The bundler turns wood waste into compressed, transportable bundles of woody biomass. The standard bundle is two-and-a-half feet in diameter by 10 feet long, weighing approximately 1,000 pounds. The bundler can produce 15 to 30 bundles an hour, the company reports, and each one contains the amount of energy equivalent to one megawatt hour of electrical power. "John Deere brought the bundler over in 2003 after the company saw the need for it here in the states," Freeland says. The 1490D is produced in Europe on a custom-order basis. Only one of these rare machines can be found in the United States right now. Marvin Nelson Forest Products, based in Michigan's wooded Upper Peninsula, purchased the machine, according to Freeland. After the machine was purchased, however, the logging firm agreed to rent the equipment back to John Deere for demonstrations, giving the $500,000 piece of equipment exposure across the country.

"Everybody's interested in biomass again," Freeland says, adding that the factory in Europe has six more Slash Bundlers on order from European customers. A second customer in the United States has arranged to purchase a bundler, too, which Freeland says should be delivered stateside by February. He stresses that the upfront capital expenditures, including boiler retooling and the bundler's big price tag, shouldn't deter companies from greening their operations. "Don't look at what you're going to spend to get this going," Freeland says. "Look at what you'll be saving. Take the figures to the bean counters in accounting—they'll understand it. Biomass is a big deal now. There are tax incentives available, and think of the positive [public relations] that goes along with being able to say, ‘We're using renewable fuels.' Deere sees and knows that there is big interest in this."

Ron Kotrba is an Ethanol Producer Magazine staff writer. Reach him at rkotrba@bbibiofuels.com or (701) 746-8385.

Several competing methods to get the oftentimes airy crop materials condensed are under investigation right now, and this doesn't necessarily involve making dense bales for transport. While some researchers are studying baling trials, others are compelled by a more mysterious pathway. Whatever the means of getting the desired materials from the source of origination to its final destination, the methods have to be cost-effective and capable of handling high volumes of materials in an efficient and not so labor-intensive fashion. Different approaches to processing materials on or near the harvest site, which are unconventional compared with baling and hauling, are also undergoing scrutinizing review.

If custom-harvest baling is the preferred method, those footing the bill are faced with the hulking consideration that hundreds of tons of biomass are needed daily to power or supply feedstock to one mid-sized refinery. To put this in perspective, a 1,000-pound horse can eat 50 pounds a day. At that rate of consumption, it would take approximately 10,000 horses to eat all of the biomass needed for gasification to power one 40 MMgy plant—for just one day. Therefore, the implements and practices that farmers already use to harvest biomaterials aren't big enough to handle the large-scale demands that would be placed on infrastructures as biomass becomes more widely used.

Frontline BioEnergy and Chippewa Valley Ethanol Co. (CVEC) are jointly working on a multiphase biomass gasification project in Benson, Minn. The partners were in the midst of early baling trials while earthwork ensued in early November to lay the foundation for a phase one, pilot-sized gasifier. CVEC General Manager Bill Lee talked with EPM about what "state-of-the-art" means when it comes to baling biomass. "At Chippewa Valley Ethanol, we don't have a lot of direct knowledge or history here for biomass collection outside of the collective traditional harvesting techniques that our farmer-owners currently do in terms of baling wheat straw or baling corn stover," he says. "So there's that type of knowledge, and, when you dig into it, that is the ‘state-of-the-art.' There are people who have done work and developed alternatives to that, but so far the practice has not evolved very much beyond that. Simple baling techniques—round bales or square bales." Three cornerstones of CVEC's biomass gasification program are economics, reliability and sustainability. "That's a lot to do, and I think anybody doing work in this area should have the same goals," Lee says.

The gathering of corn stover in quantities suitable for applications like this isn't so cut-and-dry. "Dry collection of stover is risky when you leave it in the field," says James Hettenhaus, consultant and co-founder of CEA Inc., a consulting firm currently working on a three-year, three-phase, $3-million U.S. DOE-funded project with Imperial Young Farmers & Ranchers in Imperial, Neb. "For collection of stover, the window period is short," Hettenhaus says. "If there's a rainy harvest, you might as well forget about it." Also, the longer the wet material is left in the field, there's more of a chance for microbes to eat away at the hemicellulose, he says.

Not only is there a short window to effectively collect the biomaterials, but the moisture of the biomass also has to be taken into consideration. "You need to have the baled material below 20 percent moisture to be stable—or above 60 percent," Hettenhaus tells EPM. "In between 20 [percent] and 60 percent, the stover heats up and turns black, becoming capable of spontaneous combustion."

Another area of concern is that, while gathering the crop residues, unwanted "foreign" substances—rocks, dirt, silt, clay—may become incorporated into the bales. "It would be nice if the stover didn't hit the ground," says John Reardon, Frontline BioEnergy research and development manager. "If you could do it in one pass and get grain in one truck and biomass stover in another, and scatter some of it on the field—obviously you're going to want to leave some on the field—that would be nice."

Whether a farmer practices till or no-till cropping also comes into play. A no-till farmer isn't going to make more than one or two passes over his field to harvest grain or beans and their respective biomass counterparts because it causes soil compaction. "If you're not tilling, compaction is bad," Hettenhaus says. For northern areas, where the short growing season and cold weather make no-till farming impractical, multiple passes aren't looked upon with favor either. Sweet corn and seed corn harvesters, for instance, pluck the ears of corn off of the stalks that remain in the field. "Multiple passes can create a loss of materials by knocking those stalks down," Hettenhaus says.

Off-Site Preprocessing

The bottom line is that much time, effort and money are being invested in building better baling systems. "There are a lot of people interested in moving in this direction, and I think different people will take different approaches," Lee says.

Hettenhaus says the sugar platform is one to look at as it effectively stores bagasse, the term for remnant fibrous plant material left over after sugarcane processing. Rather than harvesting crop residue like corn stover with moisture levels below 20 percent or above 60 percent, the stover would be collected at 50 percent moisture, piled and then saturated with water. "All sugar companies store bagasse wet," Hettenhaus says. "Saturating [corn stover] removes the solubles to go back into the field. When you take the solids out, it's like getting Coke with no ice." Tests have been run on converting this substrate to ethanol. "The pH is 4.1, which is good and will process better." Nearing press time, more results were expected. Taking into account the high water concentrations, Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway is helping examine how to stage it at the elevator in 100-ton railcars.

The treatment of biomass materials needs to be different, depending on the end-use application for which the organic material is destined. The collection and treatment of stover, whose end purpose will serve as energy in combustion or gasification for process heat and steam, for instance, may require different steps compared with stover destined as feedstock. When that material is intended to be fermented into ethanol, reducing it down to a concentrated mix of C5 and C6 sugars in the field will lessen the burden of loading and transporting the cumbersome stalks.

"One scheme is to go through an extrusion operation," Hettenhaus suggests. During such a process, the hemicellulose would come off, the lignin would be made soluble and the glucose sugars from the cellulose would become available. "So rather than taking all that biomass into the plant, just bring in the mix of C5 and C6 sugars," he says. Collection sites could be similar to sugar beet piles, where farmers drive in, have their truck weighed, dump their beets, are given their dirt back, and then are reweighed to adjust for the dirt content. Temporary or permanent preprocessing facilities could be located at the collection site, where such an extrusion treatment could take place. "Preprocessing is a way to meet economic targets," Hettenhaus says. "Also, it is a way to keep farmers in the value chain. How many farmers are going to own one of these cellulosic ethanol plants when they cost several hundred million dollars? None." However, if farmer-owned preprocessing outfits exist at the site of biomass collection perhaps positioned every 15 to 20 miles then the concentrated sugar stock could be economically transported to nearby ethanol refineries where little changes to existing equipment would be needed.

Maybe in the future, harvesters that process while collection is taking place will be invented. Maybe the truck running alongside the combine could be replaced with a mobile preprocessing unit to further simplify the gathering and hauling. Chevron Technology Ventures, a subsidiary of Chevron Corp. now aligned with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in a five-year research arrangement, will be investigating mobile pyrolysis units to accomplish ambitious research and development goals (see Industry feature on page 78 for more information).

John Deere's Slash Bundler

While researchers with John Deere & Co.'s research and development division couldn't offer any comment on early-stage implements for biomass collection that may be under development, those same researchers were quick to point toward the company's already developed, yet limitedly available 1490D Energy Wood Harvester—a.k.a. the Slash Bundler. The bundler is a large piece of forestry equipment that efficiently gathers and compresses debris from logging operations. "The bundler has been used in Europe for years," says Greg Freeland, a forestry applications specialist with John Deere. "In the U.S., we're 50 years behind [Europeans] in forest management."

The bundler turns wood waste into compressed, transportable bundles of woody biomass. The standard bundle is two-and-a-half feet in diameter by 10 feet long, weighing approximately 1,000 pounds. The bundler can produce 15 to 30 bundles an hour, the company reports, and each one contains the amount of energy equivalent to one megawatt hour of electrical power. "John Deere brought the bundler over in 2003 after the company saw the need for it here in the states," Freeland says. The 1490D is produced in Europe on a custom-order basis. Only one of these rare machines can be found in the United States right now. Marvin Nelson Forest Products, based in Michigan's wooded Upper Peninsula, purchased the machine, according to Freeland. After the machine was purchased, however, the logging firm agreed to rent the equipment back to John Deere for demonstrations, giving the $500,000 piece of equipment exposure across the country.

"Everybody's interested in biomass again," Freeland says, adding that the factory in Europe has six more Slash Bundlers on order from European customers. A second customer in the United States has arranged to purchase a bundler, too, which Freeland says should be delivered stateside by February. He stresses that the upfront capital expenditures, including boiler retooling and the bundler's big price tag, shouldn't deter companies from greening their operations. "Don't look at what you're going to spend to get this going," Freeland says. "Look at what you'll be saving. Take the figures to the bean counters in accounting—they'll understand it. Biomass is a big deal now. There are tax incentives available, and think of the positive [public relations] that goes along with being able to say, ‘We're using renewable fuels.' Deere sees and knows that there is big interest in this."

Ron Kotrba is an Ethanol Producer Magazine staff writer. Reach him at rkotrba@bbibiofuels.com or (701) 746-8385.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Upcoming Events