The Quest for Maximum Yield: Wet Mill to Dry Mill

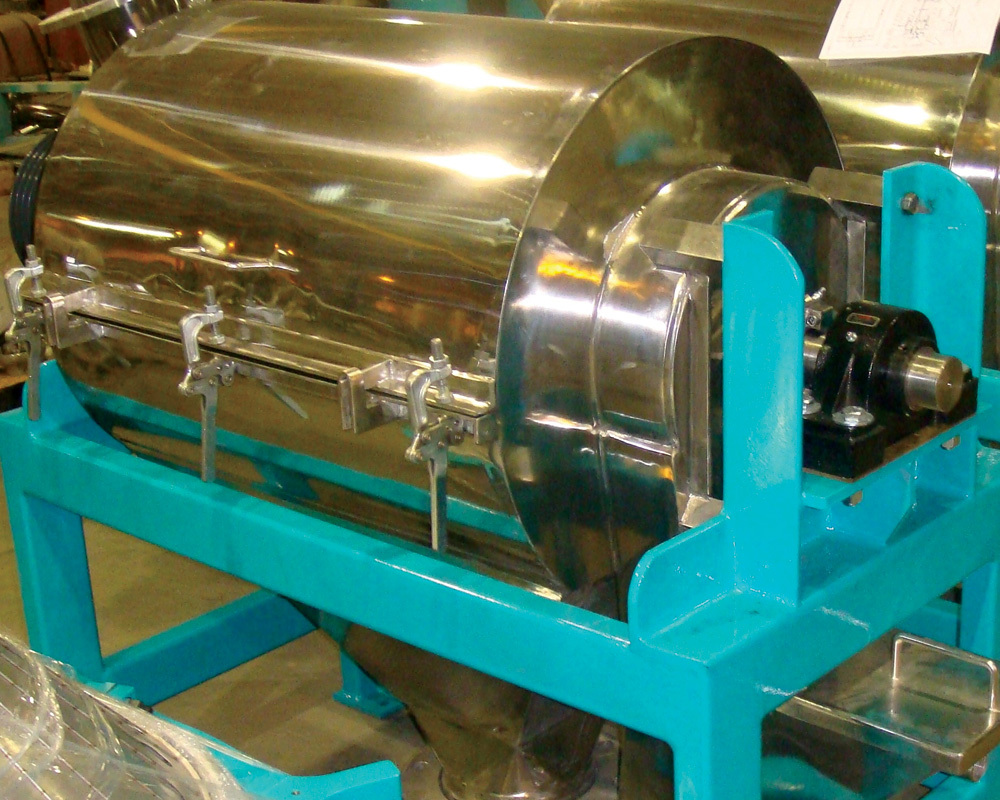

PHOTO: FLUID QUIP

August 15, 2011

BY Holly Jessen

Fluid-Quip has been well known in the wet mill world the past two decades. Five years ago, the company began searching for applications for its technology in dry mill ethanol plants, says Michael Franko, technical projects manager. As the company developed a protein recovery system, it noticed the potential for accessing more starch and increasing yield. It is now marketing its Selective Grind Technology to dry mill ethanol plants. “This equipment is standard equipment we sell regularly into the wet mills—it’s just used in a configuration for the dry mills,” he says, adding that the company has already seen a significant amount of interest from dry mills.

John Kwik, director and principal of Fluid-Quip Process Technologies, spoke about the new technology at FEW. The mill starts with a paddle screen that separates small particles and liquid from the wet grain, Franko explains. “We don’t want to waste energy and horsepower trying to grind that,” he adds. Larger particles remain on the screen and are moved to the mill where they are further processed with grind and sheer action to help release additional starch. Specifically, the system gets at the starch in the grit, or the horny endosperm, which has been traditionally hard to access. Then the liquid and ground solids stream combine in the collection tank. The process, which can also be run in series, is patent pending and utilizes proprietary plate designs. Producers could also take it a step further by installing Fluid-Quip equipment to target the liquid stream for front-end corn oil extraction, also patent pending, Franko says.

Advertisement

The system has been enthusiastically accepted at a 42 MMgy ethanol plant, where it was installed for testing. Even though Fluid-Quip built the steel structure as a “bare bones” temporary installation, the unnamed production facility was still running it in July, more than six months after it was put in place. “Once they saw the results they never wanted to turn it off,” Franko says. The system has shown a yield increase of 2.5 percent, averaged over six months. Yield increases start out higher, but decrease as plates wear. The company is studying plate life to provide a schedule of recommended plate replacement, which they anticipate will be a small cost for ethanol plants.

Besides increasing yield, plants will use less natural gas as a result of Fluid-Quip’s Selective Grind Technology, although there will be an increase in electricity use to power the system, resulting in a slight increase in energy costs at current prices. For one thing, plants won’t have to grind as aggressively with their hammer mills. Also, with less starch going through to the distillers grains, less energy will be needed for a plant’s dryers, Franko says. Some ethanol plants today are producing DDGS with 8 percent starch—that’s a lot of starch going out the door, he says. Finally, with less starch in the DDGS, producers will find the product’s protein and fat numbers will go up. “It’s exactly the same corn coming in but because you have taken that starch portion out, you’ve got a higher pro-fat number, which is very attractive to a lot of the feeders,” he says.

Advertisement

That benefit alone provides plants with the potential to up their corn oil extraction numbers. Producers capturing corn oil on the back end tell Franko that when more starch is removed from their DDGS and the pro-fat numbers go up, it allows higher rates of corn oil removal, which means more revenue. Otherwise, producers have to watch those pro-fat numbers so not to go out of spec for their customers, meaning they can’t remove as much corn oil as they have the ability to do. “You invest a lot of capital in oil recovery and you can’t even floor it because of your requirements,” Franko says. “Not only does [Selective Grind Technology] let you get extra alcohol and save you energy on drying, but it can also allow you to use that oil recovery to the fullest.”

The nice thing about this system is that it provides customers with affordable benefits today while also opening up doors to future technologies such as front-end oil extraction and separating fiber and protein through fractionation. It’s a path to becoming a biorefinery of the future with the addition of more coproducts and fiber for cellulosic ethanol, Franko says. Another exciting possibility in research and development now is the diversion of a portion of the liquids stream directly to fermentation, skipping the liquefaction step because it already contains fermentation-ready sugars. “I think we are going to see a really neat secondary yield benefit, because we pull off the sugar that is ready to go,” he says. “You don’t have sugar that travels and fills up the liquefaction tank when it doesn’t need to be there.”

—Holly Jessen

Upcoming Events