Waking Up the Bear

January 27, 2016

BY Tim Portz

In many ways, Russia’s enormity is a burden. The country is roughly twice the size of the United States, with half the population. The massive country, reaching east from Europe nearly 6,000 miles to the Bering Strait is loaded with natural resources including the world’s largest forests. One-fifth of forested lands are within Russia, much of it boreal forest, which the Russians call taiga. The predominant species in Russia are pine, spruce and larch, a cone-bearing tree that loses it leaves in autumn. This massive inventory at just under 3 million square miles is more forest than can be found in the United States and Canada combined. Despite nearly 50 percent of the land mass in Russia being covered in trees, the forest products industry in Russia is relatively insignificant, generating just over 1 percent of the country’s gross domestic product. The reality is that while Russia is practically covered in trees, it isn’t covered in roads. Russia’s forested areas are remote, subject to long winters with frigid temperatures and consequently home to almost no one. Rail lines in the interior of the country are scarce and those that exist can be found only along the southern borders of these dense tracts of forests.

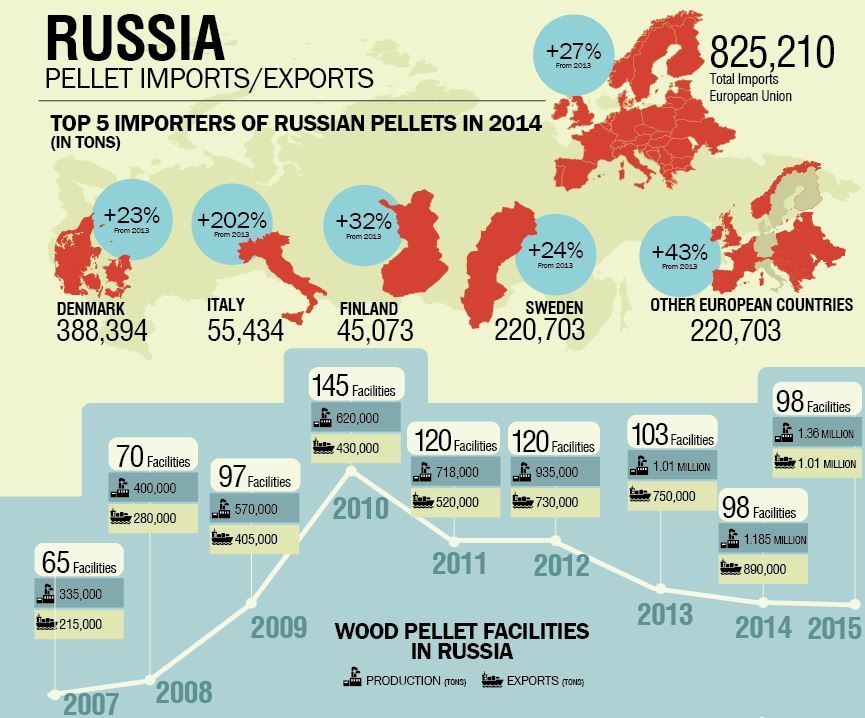

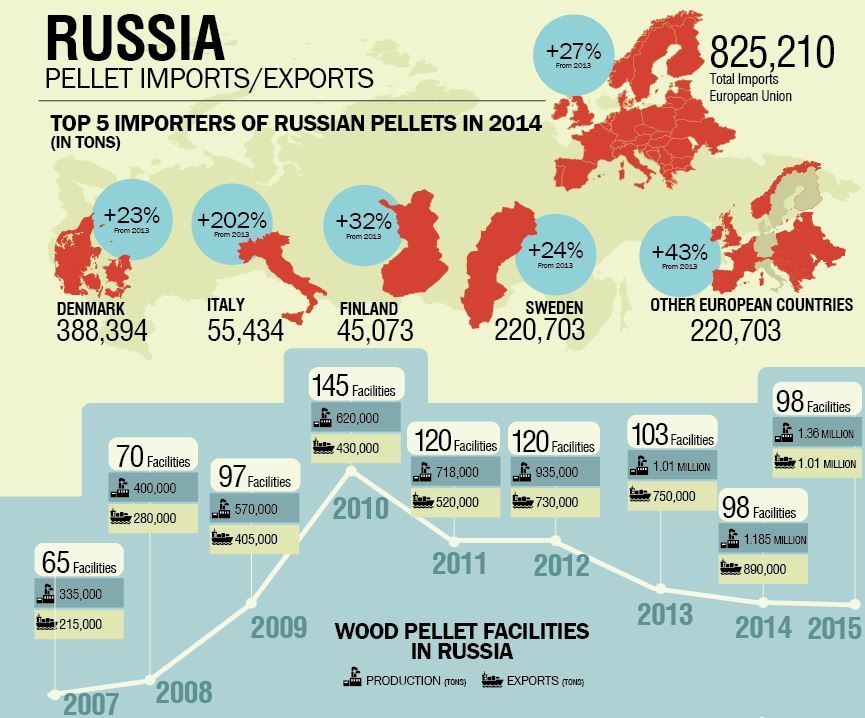

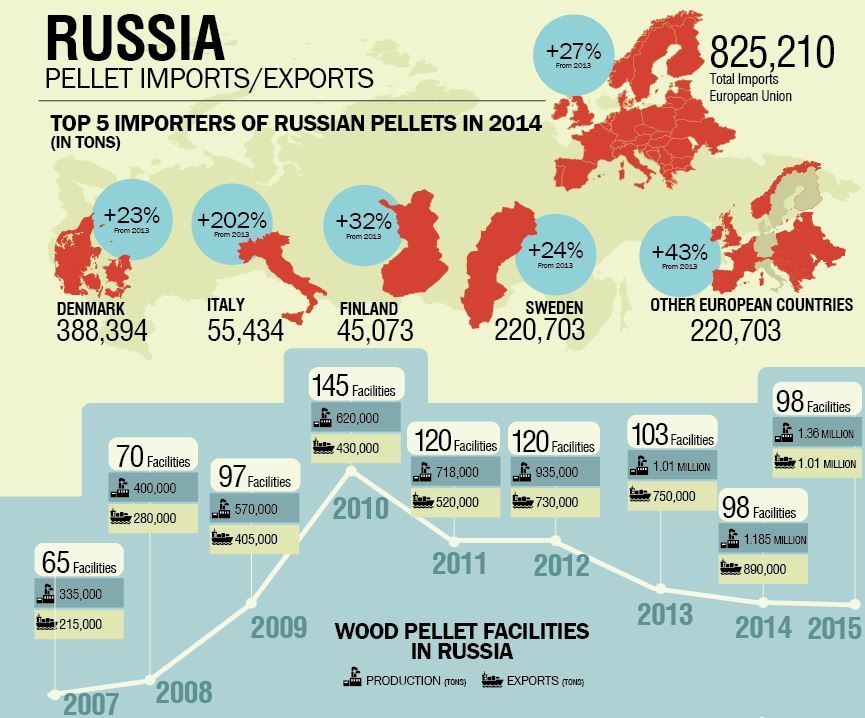

Despite all this, Russia is steadily growing its pellet industry and emerging as one of the largest exporters of wood pellets in the world. While Russia’s enormity and lack of infrastructure provides plenty of challenges for its forest products industry, it does enjoy a handful of key geographic advantages, particularly in the context of the growing European pellet market. The Baltic Sea, nestled between Scandinavia and northern Europe reaches eastward toward Russia and finds land at St. Petersburg, providing the country with an access port to pellet buyers throughout Europe. Pellet-carrying vessels departing the port of St. Petersburg are just a few-days sail from ports of call in Finland, Sweden and Denmark. Stockholm is just over a 24-hour sail nearly straight west from St. Petersburg. Russia has made the most of this proximity and Sweden and Denmark together represent over half of Russia’s current export volume. Still, industry advocates and traders inside Russia see more opportunity. Ports in established and growing pellet buying countries like the Netherlands and the United Kingdom are just another day or two more at sea beyond Russia’s current Scandinavian customers, and producers and traders are determined to earn a piece of that business as well.

Establishing An Industry

Dr. Olga Rakitova has been following and advocating for the Russian pellet industry nearly since it started. “The pellet industry started in the early 2000s when the first 6 plants were constructed in the Leningrad area (the region of Russia that surrounds the port of St. Petersburg),” Rakitova tells Pellet Mill Magazine. “Europe had a need for pellets and the Russians started production. Then more and more pellet plants were installed in Russia―mostly in the northwest near the border with Finland.” The learning curve for producers in Russia was steep and the first producers made mistakes and learned costly lessons. “The first companies bought pellet presses designed for agriculture, which was an early mistake and eventually some of them replaced them with presses designed to handle wood fiber,” she says.

The industry found its footing and grew throughout the early 2000s, gaining real momentum late in the decade, adding plants, growing capacity and exporting larger and larger volumes. The Russian Federal Statistical Service (Rosstat) reports that, between 2007 and 2010, the number of pellet facilities operating inside Russia more than doubled, growing from 65 plants to nearly 150. An exact number is difficult to obtain as many plants produce very small volumes, which are sold as animal bedding, cat litter or are aggregated by pellet brokers. “I would say right now there are around 20 to 30 pellet facilities actively making pellets for export to Europe,” Rakitova says.

In 2010, the Russian pellet industry went supersized as the Vyborgskaya Forest Corporation announced the construction of what was to become the world’s largest pellet production facility northwest of St. Petersburg, near the border of Finland. The plant was massive in every way, boasting the world’s largest woodyard, 24 hammer mills and 36 Andritz pellet presses. At full capacity, the facility would be capable of producing 1 million tons of pellets. Roundwood is ferried to the facility on river vessels making the plant the first in Russia to handle and process whole logs. Since its commissioning, the plant has struggled to maintain steady production and stopped producing at all for a period of time in 2013. “They (Vyborgskaya) are located in the harbor, but not in the most densely forested regions of the country so they have struggled to consistently get adequate feedstock,” Rakitova says. The dip in Russian pellet production in 2013 is largely attributed to the stoppage at Vyborgskaya. Still, the construction of the plant marked an inflection point in the Russian pellet industry; the end of the industry’s adolescence and the beginnings of the Russian pellet industry’s emergence as a major global player.

Maturation Process

As the industry inside Russia and opportunities within the Baltics grew, the pellet trade began to attract the attention of commodities brokers and traders. One of them, Copenhagen Merchants, saw an opportunity to leverage its experience gained over 30 years of trading and moving grain around the region in the wood pellet business. Copenhagen Merchants began working in the pellet business in 2006, aggregating and bagging wood pellets in a few terminals. In 2009, together with minority partner Sergei Genkin, the company formed CM Biomass and began trading significant volumes of wood pellets. Today, the company trades nearly 700,000 tons of wood pellets each year, a substantial amount of that Russian-produced pellets.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“We are the biggest trader exporting wood pellets out of Russia,” Genkin says. “I would reckon for this year we’ll move about 250,000 tons of Russian pellets.” Genkin manages pellet purchasing and logistics, working with roughly 30 different producers inside Russia. “Probably the biggest difference between how this business is structured in Russia when compared to the United States is in Russia we have a very small number of big suppliers, mostly around 100,000 tons, about 30 midscale suppliers, and the rest are very small suppliers, making around 500 to 1,000 tons per month,” he says.

Genkin works with his stable of producers connecting them to pellet buyers in the United Kingdom, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany. “The majority of our volume is shipped out of the port of St. Petersburg,” Genkin says. “We have a long-term agreement with the port. We currently have two warehouses and the third is under construction right now. In total, we are going to have about 25,000 tons of storage capacity at the port.” As CM Biomass trades in both premium and industrial pellets, its warehouse facility must be able to isolate inventories from one another. Genkin estimates that about 170,000 tons of CM Biomass’s annual volume moves through St. Petersburg as bulk shipments. The vessels operating in the Baltic Sea are much smaller than the handy-sized ships so prevalent in North American pellet ports. “It’s all coasters,” Genkin says. “Their capacity is between 3,000 and 6,000 tons.”

Compare and Contrast

When asked to compare the Russian pellet industry to its North American counterpart, Genkin immediately points to Russia’s lagging infrastructure. “In terms of logistics, it’s just completely different,” he says. “In Russia, we have some inland pellet facilities that in some cases are 4,000 miles from the port in St. Petersburg. So, it takes a minimum of two weeks to get to the port from where the pellets are produced.” A comparable scenario in North America is difficult to imagine, but a rail shipment from Miami to Juneau comes pretty close.

Despite the incredible distance, these remote sections of Russia, mostly in Siberia, seem likely to yield Russia’s next major wave of production capacity. “Siberia is probably the biggest deposit of raw materials for the manufacturing of wood pellets,” Genkin says. “At this point, we are buying everything we can in Siberia, almost everything that is produced there.” For Genkin, pellets produced in Siberia represent the highest quality available in Russian pellet inventories. “It stems from the fact that trees that are growing in extremely cold weather, the density of their fiber is extremely high,” he offers. “Their durability is about 99 percent and their net calorific value is often 18 and more. It is a very, very high quality wood pellet.”

Rakitova too sees tremendous opportunity for growth in Siberia, despite the challenges. “They have started to build big pellet plants in Siberia,” she says. “From my point of view, the region will be the second biggest pellet producing region within Russia very soon.” Rakitova allows that freight costs will constrain the flow of pellets from Siberia. “Right now it costs about 50 euros ($54) per ton to deliver pellets to the port of Ust-Luga (another port dealing in pellets northwest of St. Petersburg),” she says. In spite of these costs, given stagnant wages within Russia, the lack of an export tariff on wood pellets and a devalued ruble, profits can be made.

Changing Requirements

The increased demand for wood pellets within Europe, driven largely by EU member country decarbonization efforts, has brought increased public scrutiny and calls for assurances that wood pellets are produced in a sustainable manner. A group of European utilities, seeing that a fractured set of sustainability requirements would bring crippling inefficiency to the industry, formed the Sustainable Biomass Partnership to design and implement a certification framework that would satisfy the regulators inside every pellet-buying country in the region, if not the world.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The producers Genkin works with are already working toward their certifications. “SBP certification is a must to engage in European markets,” he says. Certification schemes are not new to Russia, in fact, the country trails only Canada in terms of certified forest acreage.

“We are SBP audited, and we are just waiting for the certificate,” Genkin says. “As for our suppliers, we have started the whole process in the spring of this year. We have our own sustainability team inside the company dedicated to this particular process. Currently, we have about six companies in the pipeline and we have two companies already audited and we are expecting for them to obtain the certificate in a week or so.”

Simon Armstrong, technical director at the Sustainable Biomass Partnership, confirms that there is strong interest in certification across the region. “Eleven biomass producers in Russia and five in Belarus have announced that they plan to undergo an SBP audit,” he says. While Armstrong would not disclose where those producers were in the process, he did share that as of press time no SBP certificates have been issued in Russia. It is worth noting that only three producers have been granted certificates, Westervelt Renewable Energy in Alabama and two pellet facilities in neighboring Latvia.

While CM Biomass is working proactively to achieve SBP certification and help their producers gain certifications themselves, there are consequences. “Since the new certification regulation is in place, it’s getting more and more difficult to keep the small suppliers,” Genkin says. CM Biomass buys pellets from as many as 20 smaller producers and to sell those aggregated volumes in Europe, those producers will have to undergo certification as well. CM Biomass’s certification does not cover its smaller producers. “The whole story about SBP is about the chain,” offers Genkin. “No matter who is the umbrella for all of the small producers, the whole idea is about drilling down to the bottom.” In Genkin’s view, this will make the economics for smaller producers difficult to manage. “In the long run, inevitably, they will have to close down,” he says.

The Future

In 2007, Russia exported less than a quarter of a million tons of wood pellets. In 2014, the country exported just under 900,000. More capacity continues to come online, although the picture here is less clear. In late 2013 and early 2014, some outlets reported that German Pellets intended to build a 500,000-ton pellet facility in Nizhny Novgorod. In October, German Pellets released a statement that the company would not be investing in Russia in the near future and Anne Leibold, public affairs for German Pellets told Pellet Mill Magazine in an email, “It is correct that we have been looking at a pellet project in Nizhny Novgorod but it has not become effective yet. For the time being, we are not proceeding with project.”

No one would argue that the opportunity is there for the Russian pellet industry. Industry experts believe that Russia’s share of the European import market is around 18 percent and Russian exports are growing at double-digit rates, and while opinions differ on where the European and global market for pellets will ultimately plateau, almost no one believes it’s likely to contract any time soon. For now, Russia’s wood pellet industry is overachieving relative to the rest of the forest products industries within the country. Whether Russia will be able to continue along its growth path will largely hinge on its willingness to invest in the infrastructure necessary to capture the value of its abundant forest resource.

Author: Tim Portz

Executive Editor, Pellet Mill Magazine

701-738-4969

tportz@bbiinternational.com

Upcoming Events