Yield Wild Card

September 11, 2012

BY Holly Jessen

Despite widespread drought, there are some areas of the U.S. that will bring in good, quality corn. Some regions received sufficient rain while others pulled through, thanks to location in irrigation zones. The average corn grower and ethanol producer located in the grain belt, however, has never seen anything like it and hopes to never see it again. “For a lot of folks, this is going to be a very different crop,” predicated Edgar Seward of DuPont said, while addressing an audience at the American Coalition for Ethanol conference held Aug. 8-10 in Omaha.

Most people recognize that heat during pollination will impact corn kernel production. What isn’t as commonly known is that heat during fill also causes problems, potentially impacting the amount of starch produced in the kernel, he said. In addition, the kernels themselves will likely be smaller, look more like popcorn and contain less floury endosperm, meaning they could be harder to grind, requiring more horsepower for hammer mills. “It’s just going to look different, it’s going to mill different,” said Seward, DuPont director of North American sales, biorefineries.

With such extreme heat stress, mycotoxins, such as aflatoxin, are likely to be a more widespread problem as well. That’s going to require vigilance and testing of inbound grain, Seward said. It’s something Illinois River Energy LLC, a 110 MMgy plant in Rochelle, Ill., is certainly concerned about, Neal Jakel, the plant’s general manager, told EPM. In fact, in early August, the company had already ordered 1,500 aflatoxin test kits and had started preharvest testing in the fields from which the ethanol plant typically sources corn. “Aflatoxin is going to be a major, major issue to deal with,” Jakel says.

Illinois River Energy has data to back up the fact that corn quality negatively impacts yield. In 2010, the company paid for a study conducted by the National Corn-to-Ethanol Research Center, in which six mashes containing zero to 100 percent damaged corn were evaluated for yield. NCERC used 2009-’10 season corn collected by staff at the ethanol plant, including moldy corn and corn damaged by heat due to aggressive drying. The 100 percent undamaged corn yielded 3 percent more ethanol, or about 0.08 gallons per bushel. Combining 8 percent damaged corn, the maximum allowed for No. 2 corn, resulted in a 0.014-gallons-per-bushel yield decrease while 22 percent damaged corn, the maximum allowed for No. 5 corn, added up to a 0.032-gallons-per-bushel yield loss. The study showed that, up to a certain point, it didn’t hurt to utilize damaged corn as an ethanol feedstock—as long as the plant purchased it at a discounted rate, said Sabrina Trupia, assistant director of biological research for NCREC, one of two people who prepared a 13-page report on the research. As the mixture reached 50-50 ratio, however, it did start to matter, she added.

Advertisement

Interestingly, there was no difference in starch content between the corn with no damage and the 100 percent damaged corn, indicating that there was something else about the damaged corn that inhibited yield, she said. Other study conclusions were that mass was lower in 100 percent damaged corn and moisture content of damaged corn was lower than that of nondamaged corn.

Although 2009-’10 was a wet year and 2012-’13 a hot, dry year, it’s possible corn quality issues will be similar because both years resulted in over-dried corn, one year due to aggressive drying and the second due to drought, Jakel hypothesized. However, in order to have a more concrete idea how drought will affect ethanol yield, the study should be repeated with corn from this year's crop, Trupia said. NCERC would be interested in continuing research in this area but would need a partner to make it happen. Further study on the effect of corn quality on ethanol yield would help ethanol producers come up with a good discount schedule.

In fact, besides just confirming a suspicion, developing a discount schedule is the reason Illinois River Energy asked NCERC to conduct the study in the first place. Ethanol producers need to educate area growers about what the ethanol industry is looking for in corn and how that is different from what is needed for the export or feedlot markets, which may not be as concerned about lower test weight or starch content, Jakel said. On the other hand, discounting corn too heavily will result in corn growers taking their product elsewhere. “It’s a balancing act,” he said.

Opportunities, Tools

In such a challenging year, it’s important to look for bright spots, Seward told ACE conference attendees during a panel presentation titled “Feedstock Quality and Its Impact on Profitability.” One is that drought-damaged corn containing less starch will contain more protein, oil and fiber. Another possible positive of extreme heat is that much of the corn crop will come off the field wicked dry and won’t require additional drying.

Advertisement

Another area of opportunity is the motivation factor. He sees wide variation in ethanol yield, with about 90 percent of plants in the 2.6 to 2.8 gallons of undenatured ethanol per bushel of corn, and a few yield superstars at 2.88, just short of that 3-gallon-theoretical yield number. “It’s going to be a challenging year but I’m probably more positive this year than I would be in any given year because I think it helps us as an industry,” he said. “When we were making 20 to 30 cents a gallon, we didn’t look for half a penny a gallon, honestly, a lot of plants didn’t even care. Half a penny a gallon is a lot of money right now. So what you are finding is lots of people are entering into the equation, asking more questions—what can I do to look like that 2.88 plant?”

The cliché about necessity being the mother of invention also applies. “You’re going to see people do things this year that normally they wouldn’t consider,” he said. DuPont is hearing from ethanol producers on the hunt for the cheapest starch available. That’s prompting questions about grinding 30 percent wheat or adding sorghum to the mix at plants that were previously relying completely on corn.

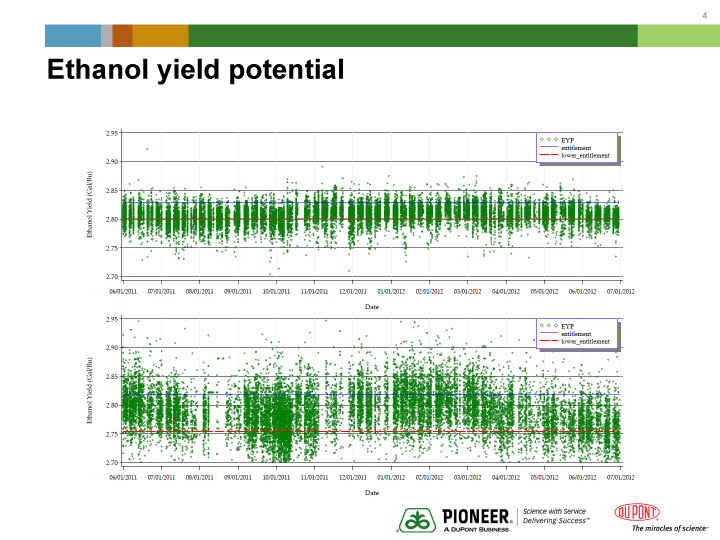

Pioneer, now owned by DuPont, has two tools ethanol producers can use to source the best quality grain. Fellow ACE conference presenter Shane Frantum, a biofuels key accounts manager for Pioneer, talked about how QualiTrak System and Dynamic Pricing Platform provide opportunities for ethanol producers. QualiTrak, an analytical tool, measures quality load by load, and summarizes that information monthly. “From top to bottom, you know exactly who is delivering the quality,” he said. “That gives you some real transparency and an opportunity to go after more of that grain.” DPP, on the other hand, can be used to aggressively go after the corn from growers or geographical regions with higher quality.

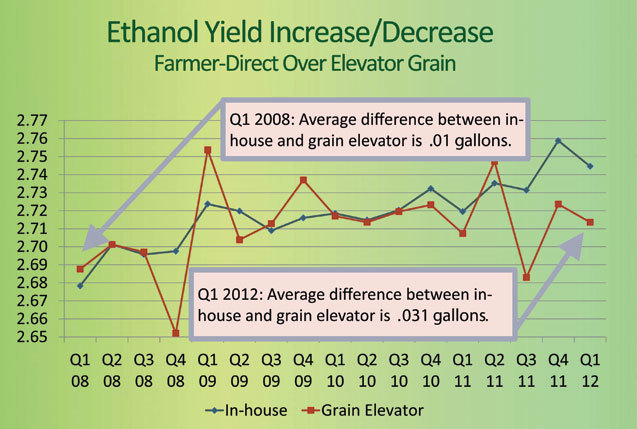

Frantum and Paula Emberland, business analyst for Christianson and Associates PLLP, also talked about the difference between sourcing grain from commercial elevators versus corn growers. Commercial elevators are good at blending corn, for fairly consistent quality year round while farmer-direct bushels show much greater variability, Frantum said. Corn sourced from farmers follows seasonal patterns, with the peak quality crop available when the new crop is harvested. Quality starts to dip in the spring and takes a hard dive throughout the summer. Although grain sourced from commercial elevators does play an important role, ethanol producers can—by purchasing more farmer-direct corn—capture value through a higher potential for ethanol yield. “When things start to dip, someone out there probably has some good quality corn,” he said. “And those are the guys that you want to hone in on and make sure that those relationships are well established and that you are going to get as much of that moving through the summer months as you can. That’s where the impact to the bottom line really comes.”

Frantum showed, using modeling, that a 100 MMgy ethanol plant could save money by going after more farmer-owned corn. In the first example he gave, a plant going from 100 percent commercial corn to 75 percent commercial and 25 percent from the farmer could save 15 cents a bushel, however ethanol yield stayed constant. If the plant increased farmer-direct bushels to 50 percent, however, it could save 10 cents a bushel while providing farmers with an incentive to deliver high-quality corn. By doing that, the facility could potentially enjoy a bump in ethanol yield from 2.782 gallons per bushel to 2.799. The difference between the two scenarios, he said, was creating a market signal for farmers. “The growers need to know that quality matters,” he said.

Author: Holly Jessen

Features Editor of Ethanol Producer Magazine

(701) 738-4946

hjessen@bbiinternational.com

Upcoming Events