Stover Pellets Pack in the Pounds

September 17, 2014

BY Susanne Retka Schill

Pelletizing corn stover offers some tantalizing prospects. Where it is virtually impossible to load a truck to maximum weight with bales, one could with pellets. The densification process improves bulk density by a factor of four. On top of that, stover pellets should be able to be stored and handled much like corn, essentially turning them into a commodity that could be shipped anywhere.

The wood products industry has done this, taking the waste stream from sawmills and densifying sawdust into pellets. In some cases, forest slash and thinnings are used as well. Premium pellets are catching on in U.S. regions where high propane and fuel oil costs make pellet heat very affordable. And, the pellet industry is booming right now in the Southeast, where producers are filling the holds of ships with industrial wood pellets bound for European power generators, for cofiring or replacing coal.

There is a science to pelletizing. Particle size and distribution, moisture and components such as lignin, protein and starches are critical factors in densification. The lignin in wood, for example, essentially melts under the pressure and heat in a pellet die binding particles together. Starch is the preferred binder for medicine tablets and the protein in alfalfa binds feed pellets. Researchers at Idaho National Laboratory have studied the components and processes in densification, along with the systems in use to manufacture different forms, such as briquettes, range cubes, tablets or pellets. Among the many crops examined, some require binders due to low lignin content, such as switchgrass or miscanthus.

Corn stover makes a good durable and dense pellet, reports Jaya Shankar Tumuluru, an expert on pelletizing biomass materials at INL. He was the lead author in a 2011 paper on biomass densification systems for bioenergy application. “Stover pelletizes without binders, at a reasonable energy consumption,” he says. The lignin and water-soluble carbohydrates in stover make it easier to pelletize than some energy crops. Under the pressure of a pellet die, the moisture and steam help create binding forces, and along with that, the spherical shape of finely ground stover helps with densification. INL research has shown that pelletizing corn stover doesn’t introduce recalcitrance and, indeed, may improve an enzymatic conversion process by breaking down some of the structures in the cellulose and hemicellulose to make the sugars more accessible, he adds.

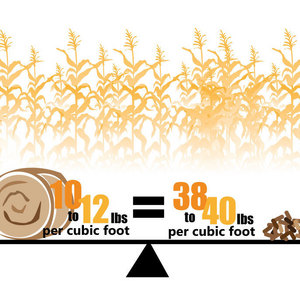

“Currently the transportation cost saving does not totally offset the costs associated with the pelleting and regrinding at all transportation distances,” he says. “But that said, we have not quantified additional advantages such as handling and storage benefits of pellets in terms of cost per ton,” he continues. “If these costs are quantified, then we think the costs can be tipped in favor of pelletization.” After all, pellets pack the same weight in about one-fourth the volume. Stover pellets weigh 38 to 40 pounds per cubic foot compared to 10 to 12 pounds per cubic foot for bales. Pellets provide other storage advantages besides a much smaller footprint, he adds. “The 5 to 10 percent moisture content improves storability, plus pellets have good flow characteristics in handling systems,” he says. “A corn grain handling system should be able to handle stover pellets.”

Applied Technology

A Nebraska company is aiming to be among the first to turn cumbersome bales into a storable and transportable commodity, with biorefineries only one of several potential markets. Stover pellets could become a replacement for coal in power generation, and they could revive traction for stover in the feed market.

“With our technology, 75 percent [of the process] is the same, whether the pellet is going to biochemical, biocombustion or feed,” says Russ Zeeck, chief operating officer of Pellet Technology USA. He founded the company six years ago after selling his interests in the ethanol industry where he had worked for 15 years. Studying the cellulosic space, he launched a corn stover based-business, partly because stover itself is a very consistent biomass for cellulosic processes, and partly because, in his assessment, stover will dominate the biomass feedstock scene as energy crops take time to gain ground.

Pellet Technology has collaborated with ICM Inc. to realize its goal. Earlier this year, the two companies announced an agreement for ICM to become the engineering, procurement and contracting agent for future facilities and a strategic partner for the development and commercialization of the technology. ICM has helped with engineering and fabrication of system components, and handled last year’s expansion of the R&D center in Gretna, Nebraska. Pellet Technology expects to be announcing the first commercial facility soon, Zeeck reports, and should be breaking ground on a full-scale 200,000 ton per year plant in the Midwest by the beginning of the new year.

The initial target market is for feed. “Why we went with feed is because farmers have issues with stover on the field now,” explains Joe Luna, Pellet Technology’s biomass and site coordinator. And, though the price of corn has dropped considerably since the drought-driven peak of $8 per bushel sent feeders looking for alternatives, emerging technology in the ethanol industry is likely to impact the livestock industry as well. Low-oil distillers grains is already affecting rations, and the expected move toward removing fiber will require further adjustment. Pellet Technology has patented an engineered feed pellet that transforms stover into a nutrient-dense feed and almost doubles its digestibility, Luna says. And, high-protein distillers grains and syrups from the ethanol process are used in some feed formulations.

A big part of Pellet Technology’s intellectual property surrounds the grinding and handling of stover. “Stover is not an easy animal,” Zeeck says, explaining that when ground, stover’s very light specific gravity means it handles very differently from ground corn. Engineering solutions had to be found for material handling, transitions and mixing, with a watchful eye on dust control in anticipation of permitting requirements. Another important goal was to reduce the 10 to 12 percent loss factor observed in the typical tub grinders that served as the platform for Pellet Technology’s modifications.

Another focus was on developing a consistent product, Luna explains. “In the traditional method of handling corn stalks—tub grinders—there’s a pulverizing action, a lot of dust produced and particles anywhere from dust to 2 inches long, depending on the screen size. Part of our intellectual property is to have tight control on particle size.” The process also needed to successfully handle bales of different types and sizes, coming from places like northern Nebraska or eastern Iowa. Real world conditions mean those bales will vary from 10 to 50 percent moisture, with some having been sheered once in the field, some twice and some not at all.

The pellet process was also extensively modified. Luna explains the company started with a standard pellet press. “We changed the roller, the die and the feed system,” he explains. “We do not use steam in our pelleting, and we control our die temperature.” Heat created by friction needs to be controlled to avoid degrading components that impact yields in a biochemical process, he explains, or to avoid affecting the Btu content for cofiring applications.

Zeeck and Luna envision Pellet Technology being an add-on for first- or second-generation ethanol facilities, or deployed in co-op fashion. Farmers would bring baled stover in to strategically located facilities where it is pelletized for the intended market and stored for later shipment. Building on the familiar grain-handling model, such a system could aid the development of the biomass market, giving sellers alternative markets and buyers more sources. Sustainability will be a concern, Zeeck adds, to ensure soil and conservation goals are met for farmers. And, though feed is the initial market, there is tremendous potential for growth in the biomass market, based on the sheer volumes that will be required, he adds. “We’re talking to one biochemical developer who alone is looking at 800,000 tons of stover per year.”

Author: Susanne Retka Schill

Senior Editor, Ethanol Producer Magazine

701-738-4922

sretkaschill@bbiinternational.com

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Related Stories

The USDA reduced its forecast for 2024-’25 soybean oil use in biofuel production in its latest World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates report, released March 11. The outlook for soybean oil price was unchanged.

The Canada Boarder Services Agency on March 6 announced it is initiating investigations into alleged dumping and subsidizing of renewable diesel from the U.S. The announcement follows complaints filed by Tidewater Renewables Ltd. in 2024.

The U.S. exported 27,421.8 metric tons of biodiesel and biodiesel blends of B30 or greater in January, according to data released by the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service on March 6. Biodiesel imports were at 9,922.4 metric tons for the month.

Lawmakers in both the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate on March 6 reintroduced legislation that aims to ensure that RINs generated for renewable fuel used by ocean-going vessels would be eligible for RFS compliance.

The U.S. government on March 4 implemented new tariffs on a variety of goods from Canada, Mexico and China, including a 10% tariff on biofuels entering the U.S. from Canada. Future retaliatory tariffs could also impact U.S. biofuel exports.

Upcoming Events