Ethanol faces a terminal challenge

August 15, 2016

BY Ann Bailey

Changes to existing terminals will need to be made if higher octane fuels are added to the U.S. fuel supply, says Kristi Moriarty, National Renewable Energy Laboratory senior analyst. While a groundbreaking NREL study indicated that there are few technical issues associated with storing and distributing ethanol, there are several significant factors that could limit increased distribution of ethanol.

Terminal companies indicate that most of their tanks are in use, which means that accommodating ethanol at a volume of 25 to 40 percent likely will require that new tanks and other equipment be installed, the NREL study says. The Department of Energy conducted the research into terminal availability because the agency previously had spent a lot of time studying retail stations and no time on terminals, Moriarty says. The U.S. expects to distribute more biofuels so it is important to understand the impacts, opportunities and barriers across the fuel supply chain, the NREL report says.

The study, “High Octane Fuel: Terminal Backgrounder,” included interviews with personnel at terminal companies and visits to several to learn how ethanol is handled, about issues with storage of the biofuel and about the potential for terminals to store more ethanol. “We decided to publish a report with some background information on [terminals] with the understanding of how they work and the fuels flow through them, so there’s a more complete picture supplied by those industries and the Department of Energy,” Moriarty says. The study focused on gaining an understanding of terminals and determining if they could handle more ethanol if a high-octane fuel (HOF) of a 25 to 40 percent ethanol blend entered the marketplace. Previous fuels infrastructure studies funded by DOE looked at retail and fleet stations and whether they could store and dispense ethanol blends, E10 and other biofuels, the NREL report says. The new backgrounder study focused only on terminals.

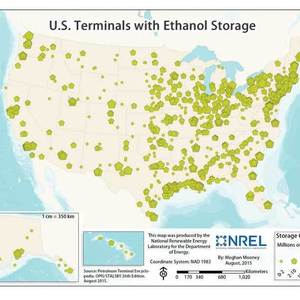

According to the Oil Price Information Service, there are 1,296 terminals across the United States storing transportation fuel and nearly all—more than 1,200 terminals in all 50 states—either do or can store ethanol, the NREL study says. For the 363 terminals reporting ethanol capacity, the nationwide average was 12,867 barrels (540,000 gallons), varying from a low of 238 barrels to a high of more than 490,000.

Before she conducted the study, Moriarty assumed that ethanol arrived at terminals via rail. “I was surprised that most of the ethanol was delivered by truck to the terminals,” she says. “Prior to the study, we weren’t aware they weren’t able to deliver unit car trains, in most cases. Certainly some of the terminals can.” According to the study, the majority of ethanol is delivered by rail to transmodal facilities where it is then trucked to terminals.

The inability of terminals to accommodate unit trains presents a challenge for the ethanol industry, Moriarty says. “Because if you’re receiving by truck you’re going to have to have more land available and more off-loading facilities,” Moriarty notes. Meanwhile, some terminal owners require that staff is on-site to receive ethanol, which means that the terminals only can receive ethanol during daytime hours, Moriarty says.

The study also found other factors that could limit additional ethanol being delivered to terminals include:

• Permitting and regulatory processes to add tanks have become more time-consuming and challenging in recent years, according to all of the terminal companies interviewed for the study. Equipment is aging, but it is difficult to upgrade or replace equipment while maintaining permits and normal operations.

• There are few existing tanks that are not already in use.

• It will be necessary to reconfigure the existing loading racks and bays to accommodate additional equipment to fill trucks.

• A significant amount of capacity is leased to customers under long-term contracts to store specific fuels and volumes.

Terminals are capable of handling more additional ethanol if the market indicates there is enough long-term demand to warrant building more infrastructure, the NREL report says. But terminals now are designed to serve the current market and generally don’t have extra tanks or the capacity within their existing tanks, the NREL study says.

The report says that when terminal companies were interviewed for the study in spring 2015, they indicated that they had few unused tanks and weren’t able to supply E15 to all of their customers because they didn’t have enough infrastructure to handle it and the same would be true for a high-octane ethanol blend. That meant if they were going to store more ethanol, that typically would require the addition of a new tank and equipment such as piping, valves and pumps to connect it to the loading equipment.

Some members of the ethanol industry took issue with the idea that new tanks might be needed, Moriarty says. She disagrees. Many of the existing tanks are leased under a 10-year contract, which means that the company, which could be a retailer, fuel marketer or other business would have to be on board with any changes, she notes. “You would have to commit them, who have this long-term contract for a particular fuel.” While some companies will be able to repurpose tanks, new tanks also will need to be installed, Moriarty says. “To be clear, that’s to service a high-octane market in the E25 to E40 range. All of the tanks in this country are in use and they’re either storing a BOB (blendstock for oxygenate blending) or a diesel or a jet fuel or asphalt or some other product.”

During the past year, the industry has taken concrete steps to increase the number of terminals that store ethanol. Companies that have announced they are building terminals include Flint Hill Resources, which is constructing its first ethanol terminal at its Buda, Texas, hub. Meanwhile, Green Plains Partners LLP and Delek Holdings Inc. said last year they planned to form a 50-50 joint venture to build a $12 million ethanol unit train terminal in Maumelle, Arkansas, on the Union Pacific rail line, and this summer JP Energy Partners LP revealed it began expanding its rail facilities in its North Little Rock refined products terminal to accommodate unit train deliveries of ethanol.

Author: Ann Bailey

Associate Editor, Ethanol Producer Magazine

abailey@bbiinternational.com

701-738-4976

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Related Stories

U.S. fuel ethanol capacity fell slightly in April, while biodiesel and renewable diesel capacity held steady, according to data released by the U.S. EIA on June 30. Feedstock consumption was down when compared to the previous month.

XCF Global Inc. on July 8 provided a production update on its flagship New Rise Reno facility, underscoring that the plant has successfully produced SAF, renewable diesel, and renewable naphtha during its initial ramp-up.

The USDA’s Risk Management Agency is implementing multiple changes to the Camelina pilot insurance program for the 2026 and succeeding crop years. The changes will expand coverage options and provide greater flexibility for producers.

EcoCeres Inc. has signed a multi-year agreement to supply British Airways with sustainable aviation fuel (SAF). The fuel will be produced from 100% waste-based biomass feedstock, such as used cooking oil (UCO).

SAF Magazine and the Commercial Aviation Alternative Fuels Initiative announced the preliminary agenda for the North American SAF Conference and Expo, being held Sept. 22-24 at the Minneapolis Convention Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Upcoming Events