Feedstock State of Affairs

December 17, 2024

BY Sue Retka Schill

Imports of used cooking oil (UCO) and tallow have exploded, paralleling the rapid increase in renewable diesel (RD) capacity and production. Renewable diesel capacity grew from approximately 859 million gallons at the end of 2020 to 3.86 billion gallons in 2023, with production more than doubling, reports the USDA’s Economic Research Service in its analysis, “Oil Crops Outlook: July 2024.” Imports of animal fats (tallow and poultry fat) and greases (including used cooking oil) doubled in one year from 2.2 billion pounds in 2022 to 5 billion pounds in 2023, which accounted for just under half of the total 11.9 billion pounds of animal fats, waste oils and greases used for biofuel production in 2023. Imports from China in particular raised eyebrows, as they rose from zero in 2021 to 1.5 billion pounds in 2023, comprising over half of all imported fats, oils and grease (FOG).

Questions quickly arose to whether the Chinese UCO could be adulterated with virgin palm oil. The jury is out on that claim, however. The issue first surfaced in Europe in early 2023. In its August 2024 annual “EU Biofuels” report, the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service says widespread concerns about mislabeling and fraud of UCO biodiesel from China “led to investigations, albeit so far without conclusive results.” The International Sustainability and Carbon Certification responded to the claims of potential fraud with unannounced audits, resulting in seven certificates being suspended or withdrawn. “However, the sanctions of these seven economic operators did not conclusively indicate criminal behavior,” the ISCC reports on its website.

In the U.S., a June letter from a bipartisan group of six senators, led by Sen. Roger Marshall, R-Kansas, to multiple federal agencies expressed concern with the dramatic increases in UCO imports from China that may be a blend of UCO with virgin oil. They noted that domestic sources of UCO are held to rigorous verification and traceability requirements, but expressed concern with the lack of transparency surrounding U.S. efforts to verify imported UCO.

Replying to emailed questions, EPA says that contrary to some media reports, “the referenced investigations were routine Renewable Fuels Standard inspections that evaluate all aspects of the companies’ compliance.” Declining to provide details on ongoing investigations, the agency’s spokesperson says direct oversight is largely supported by records that must be audited by independent third parties annually. EPA also inspects facilities and reviews the records of renewable fuel producers.

Asked about the challenge in verifying the authenticity of UCO, EPA says the chemical analyses producers use to ensure compatibility with their process “are effective at identifying feedstocks like virgin vegetable oil, which are not used cooking oil.” Such analyses are not definitive, however, and testing techniques are still a developing field of analytical science.

Feedstock Challenge

Raising the question of imported UCO with industry spokesmen quickly shifts to a broader discussion of the feedstock challenge. It’s not just about UCO imports, but all the feedstocks that play in the mix for biomass-based diesel fuels (BBD), says Donnell Rehagen, CEO of the Clean Fuels Alliance America.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Biodiesel, renewable diesel and (eventually) sustainable aviation fuel production, all pull from the same pool fed by five feedstock supplies, he says, which just isn’t large enough. Using all the domestic feedstocks combined, he says, would produce between 3 billion and 3.8 billion gallons of BBD. That’s figuring in about half the soybean oil crush (with the other half bound for food use) plus all of the domestic animal fats, distillers corn oil and canola oil—which, he adds, is unrealistic because those feedstocks have other uses as well. “We’re a 5 billion gallon industry—where does the rest come from?”

The growth in BBD capacity is virtually all renewable diesel, with the biodiesel industry’s capacity in the 2-billion- to 2.5-billion-gallon range. RD capacity is expected to continue to grow, Rehagen adds, to about 4 billion gallons next year. “These are massive plants—700 MMgy plants. We have very few biodiesel plants that are even 70 MMgy.

“One of the logistical challenges that RD producers have when they scale like that is they need a massive amount of feedstock every single day,” Rehagen continues. “We are the largest consumer of soybean oil in the U.S.; we use a little more than food. We use everything that’s available, but we have needs beyond that. And when you think about it, these RD plants are not ideally located to bring in soybean oil or canola oil.”

Most of the largest RD facilities are retrofitted oil refineries located on West Coast and Gulf ports, he points out, and thus, logistically situated to handle imports.These RD facilities are using as much feedstock in one day as some of our biodiesel plants use in a year, Rehagen says. “That’s not a knock on biodiesel at all, it’s just the reality of how those plants have come online. They are massive consumers of feedstocks, and they need to have it every day. That’s where the challenge has become trying to balance their needs to produce at the levels they need to, with the availability and logistics of all the domestic feedstocks. You throw on top of that LCFS [low carbon fuel standard] markets like the one in California, and that distorts everything.”

The LCFS has created impressive demand for renewable fuels, Rehagen adds. “It’s a 3 or 4 billion-gallon-a-year diesel market and almost three-fourths is now biodiesel and renewable diesel. It’s a massive amount flowing into California.”

Policy Distortions

The distortion Rehagen refers to comes from how various fuels earn valuable carbon credits under the California Low Carbon Fuel Standard. All transportation fuels are scored for carbon intensity (CI) based on the greenhouse gas emissions associated with producing, distributing and consuming the fuel, which includes feedstock data. Fuels scoring above the standard for the year must buy credits from fuels with lower CI scores. Averaging all the pathways scored in California’s LCFS, renewable diesel from soy scores around 57 gCO2g/MJ compared to 23.7 g for RD from UCO. “A renewable diesel or biodiesel producer wanting to access this California market has reason to buy the lowest-CI feedstock they can get their hands on because they can make more money,” Rehagen says. “The top of the heap in California is UCO, and works its way down through animal fats, distillers corn oil, soybean oil and canola oil. It has this distorting effect on feedstock. The largest supply is soy oil, but unfortunately under the California’s low CI program, it’s the least valuable feedstock for a fuel going into California.”

For the soybean industry, the surge in FOG imports adds to soybean oil’s struggle to maintain market share. Feedstock demand for both both RD and biodiesel grew by more than one-third from 19.2 billion pounds in 2021 to 32 billion pounds in 2023. The share of animal fats and processed oils (primarily UCO) increased from 32% to 37% while the share of vegetable oils (soy, canola, corn oil) declined from 68% to 63%. Between 2022 and 2023, soybean oil’s share of BBD feedstock declined from 44% to 40%, and in the first four months of 2024 declined to nearly 33%, the Oil Crops Outlook noted.

Advertisement

Advertisement

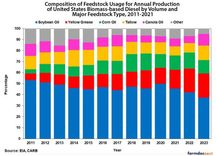

Soybean’s declining share in BBD production is illustrated in charts developed by University of Illinois ag economists. Through 2023, the volume of soybean oil used for BBD grew while its share declined, particularly since 2020 (See Figure 1). Soybean crushers who are planning expansions to meet expected RD growth look askance at soybean’s declining share and the burgeoning imports.

Soybean oil use has been increasing, says Scott Gerlt, American Soybean Association chief economist, but not to the expected utilization levels. “We’ve been building out domestic crush plants to provide more soybean oil,” he says, “and we have seen more use, but are concerned about underutilization of oncoming assets.”

He points to an analysis of what EPA expected for feedstock use when setting the renewable volume obligations (RVOs) for 2023-'25 under the Renewable Fuel Standard, compared to what has happened. The assumptions for 2023 were close to reality, Gerlt says, but in 2024, BBD production from FOG skyrocketed while production from soybean oil flatlined. (See Figure 2).

The impact on the domestic soybean oil industry is significant. The FOG BBD production of 580 million gallons in excess of EPA projections amounts to 4.7 billion pounds of soybean oil being displaced, Gerlt calculates, which would have come from 11 average crush plants processing soybeans from 7.5 million acres of soybeans. If you add to the 500 million gallons of finished renewable diesel imports that are assumed to be waste based, the total would displace the oil crushed at 20 plants processing soybeans from 14 million acres. “EPA was assuming a certain amount based on soybean oil production capacity,” Gerlt says, explaining the ASA had to show EPA how much crush expansion was coming online. In setting the blending levels for BBD, EPA assumed a certain amount coming from soybean oil, the typical usage of other sources and very little imported feedstock. “In fact, for 2025, they assumed imports at zero,” he says. The EPA got it wrong, but in fairness, he adds, few saw the surge in imports coming.

The RVOs, in essence, set a fixed blend rate, Gerlt argues. So, the growth in imports effectively pushes soybeans out of biofuel use at the margins. On top of that, the California LCFS puts soybean oil feedstocks at a disadvantage, and new rules will likely intensify that. The rules, adopted in November for the LCFS, add traceability requirements and call for capping vegetable oils (soybean and canola) at 20% of a facility’s production, with any excess receiving the conventional fuel score. “That’s going to make the situation even more extreme, because companies are going to have to switch away from soy/canola and look for waste feedstocks,” Gerlt says.

The new Clean Fuel Tax Credit (45Z in the Inflation Reduction Act) may offset some of the disadvantages for soybeans. The credit applies only to domestically produced fuels, and there’s a bipartisan effort in Congress to extend that domestic requirement to the feedstocks used for qualifying fuels. “If that were to go into effect, it would help the situation,” Gerlt says, “although considering some of the changes in California, I’m not sure it would completely shut off imports.” The playing field may also be leveled some, he adds, if the 45Z rules giving lower CI scores for feedstocks produced with conservation practices are easily implementable by farmers and biofuel producers.

Contact: Anna Simet

Editor, Biodiesel Magazine

asimet@bbiinternational.com

Related Stories

The U.S. EPA on July 8 hosted virtual public hearing to gather input on the agency’s recently released proposed rule to set 2026 and 2027 RFS RVOs. Members of the biofuel industry were among those to offer testimony during the event.

The USDA’s Risk Management Agency is implementing multiple changes to the Camelina pilot insurance program for the 2026 and succeeding crop years. The changes will expand coverage options and provide greater flexibility for producers.

The USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service on June 30 released its annual Acreage report, estimating that 83.4 million acres of soybeans have been planted in the U.S. this year, down 4% when compared to 2024.

SAF Magazine and the Commercial Aviation Alternative Fuels Initiative announced the preliminary agenda for the North American SAF Conference and Expo, being held Sept. 22-24 at the Minneapolis Convention Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Scientists at ORNL have developed a first-ever method of detecting ribonucleic acid, or RNA, inside plant cells using a technique that results in a visible fluorescent signal. The technology could help develop hardier bioenergy and food crops.

Upcoming Events