Matching For More

September 22, 2021

BY Melissa Anderson

The warning Dean Drake and others heard at a General Motors global warming summit in 1989 was both clear and alarming: the levels of carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere are rising—fossil fuel emissions are to blame—and it will soon cause a potentially dangerous planetary temperature increase. That and other early notices went mostly unheeded for two decades as novel global warming predictions of the ’80s and ’90s evolved into today’s scientifically indisputable climate crisis.

The developed world has benefited from fossil fuels for over a century, and it is now scrambling to make up for it. Along with the proliferation of renewable energy—bioenergy, solar and wind—the age of electric vehicles (EVs) appears imminent—their widespread adoption is now a matter of time, public acceptance and momentum. Most predict EVs will mostly replace the internal combustion engine (ICE) within three or four decades. However, with the Biden administration calling for EVs to make up 50% of all new vehicle sales in the U.S. by 2030, an earlier transition seems plausible.

Drake, however, says we should step back and consider our options. He offers an alternative future where ICE vehicles persist much longer, and more abundantly than predicted, with higher-ethanol blends matched with octane-optimized engines offering as much, or more, carbon reduction as EVs. His plan isn’t simple or easy; it requires an unprecedented degree of alignment among the biofuels, petroleum and automotive industries that, to date, has been elusive. And Drake has seen windows of opportunity like this close quickly before.

Early Opportunities Lost

Drake, a former GM public policy analyst and founder of the Michigan-based consulting firm Defour Group LLC, says that, in addition to high-level, inter-industry cooperation, proactive policy development is a must.

“I was part of a company that believed the best way for the auto companies to survive and prosper was not to just blindly fight regulations but develop regulations that helped the company adapt to the future,” he says, explaining that his work in the ’80s and ’90s with GM placed him at the forefront of policy and regulations including cap-and-trade and concepts that would eventually be incorporated into the Renewable Fuel Standard.

Drake helped organize GM’s global warming summit 32 years ago, and he believes the world would be in a better position today if action would have been taken then. “We could have put together a package that, by now, would have taken climate change out of the picture, he says, explaining that legislation based on work done by GM and the Environmental Defense Fund in the early ’90s under the first Bush administration could have reversed the build-up of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere we are seeing today. As early climate change policy stalled, opportunities for successful climate change response diminished.

In late 1992, GM underwent a management upheaval that changed the course of the company and the direction of the U.S. automaker involvement in climate change mitigation. For the next seven years, Drake worked in the shadows, continuing his pursuit of ecofriendly car policies. A signal that his work was never going to reach fruition came in 1999 when GM introduced one of the least fuel-efficient vehicle in its history, the Hummer. A short time later, Drake retired from GM.

Next Stage, New Vision

Never losing interest in clean automotive solutions, Drake reemerged from retirement in 2007 intent on combating climate change. He founded Defour Group with some retired GM coworkers and climate summit collaborators. Together they worked with ethanol interests studying the economics and environmental benefits of high octane, low carbon mid-level ethanol blend fuels. Now, with his focus on biofuels and climate change front and center, he sees EVs emerging as the next big evolution in automotive transportation, and he gets it.

“The electric vehicle just has a lot of inherent advantages,” he says. “It has no tailpipe emissions and people keep forgetting the importance of local toxic pollutants. One of the things you’re doing is putting pollution out in a single smokestack away from the cities instead of in front of someone’s windows.”

And perhaps the biggest advantage EVs have over their liquid fuel rivals, he says, is that more energy—nearly 80 percent—reaches the wheels, versus the most efficient liquid fuel cars getting only 40 percent of potential energy to the wheels.

But EVs aren’t perfect. The transition will require trillions of dollars of new infrastructure spending, and sources of electricity are varied, ranging from fossil fuels to eco-centered wind and solar, which is intermittent. Electric vehicles are only practical for light-duty applications—long-haul EV trucking is still not viable—and only half of the vehicles in the world are currently light-duty, urban-based cars and trucks. EV range is improving but still limited at 60 to 300 miles between charges, and batteries are heavy and dubious from an environmental and human rights perspective. Furthermore, it is predicted that more than 50% of all cars and trucks on the road will still be ICE vehicles in 2050, meaning practical solutions to reducing the carbon intensity of liquid transportation fuels today, and over the next 30 years, are needed.

Drake believes ethanol is the answer. “Biofuels are really the greatest alternative for the rest of the fleet that cannot be electrified, and that’s probably half the fleet or more,” he says. “Ethanol is the best contender.”

Blending Models

While ethanol and gasoline are reluctant but ubiquitous companions today, a more evenly balanced integration of the two fuels—not just utilizing ethanol as a blend stock, but treating it as an harmonizing octane mate—would have immense benefits for both industries, especially with optimized blending.

Drake believes mid-level ethanol blends like E30 are a perfect fit if the fuels and automotive industries come together and treat the engines and ethanol blends like an integrated system to optimize vehicle efficiency and lower emissions. Higher compression engines would benefit the most from these higher blends, he says, explaining that current automakers could quickly recalibrate existing engine setups to benefit from higher ethanol blends in a matter of a few years.

He says that while adding more ethanol to regular gasoline (splash blending) will reduce the resulting fuels’ carbon intensity, match blending the fuel (adding ethanol to a gasoline specifically blended for use with higher ethanol blends) at the “sweet spot” of 20 to 30 percent ethanol, could produce a low-carbon fuel that also lowers local toxic emissions by reducing aromatics. New vehicles optimized to run on this fuel could have the lifetime environmental impact of electric vehicles. And vehicles on the road today could also use the higher ethanol blends.

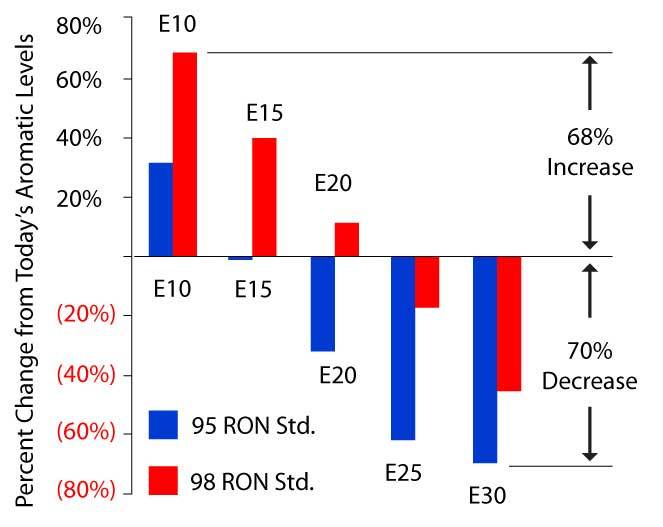

Speaking at the 2021 International Fuel Ethanol Workshop & Expo in Des Moines, Iowa, in July, Drake explained that ethanol increases RON (research octane number) octane in gasoline more effectively that the aromatics refiners routinely use to achieve desired results. Based on modeling done by the Defour Group, he says only E20 and E30 could meet a 95 RON octane standard when additional ethanol is added to regular blend stock. While splash blended E30 can achieve decreased aromatic levels by as much as 29%, Drake says match blended E30 optimized for low aromatic content can achieve a 70% decrease.

He says establishing octane and aromatic standards for fuel now is the key to allowing ethanol to fulfill its true potential and, ultimately, enable liquid fuels to achieve low-carbon parity with EVs.

Possible Effects

Steve Vander Griend, fuel and engine technology manager with Urban Air Initiative, attended Drake’s presentation in Des Moines and spoke with him afterwards. While Vander Griend thinks the easiest and most readily available solution is to splash blend ethanol into current gasoline, he appreciates Drake’s overall vision.

“Dean’s approach to aromatic reduction is high level by taking the octane blending value of aromatics compared to the octane blending value of ethanol,” says Vander Griend, explaining that Drake’s concept is relevant to a soon-to-be-released study that shows how ethanol has already significantly reduced aromatics in the U.S. gasoline supply by moving to an E10 market.

Vander Griend agrees with Drake that mid-level blends should strive for low-carbon parity with EVs, and ethanol’s ability to reduce aromatics in the fuel supply is key. “We often project the carbon reduction of an optimized vehicle on E30 but don’t talk about how current vehicles are benefitting from ethanol displacing aromatics and reducing vehicle emissions in urban areas today,” he says. “EPA models don’t credit ethanol for this reduction, further complicating the ability to truly compare the carbon intensity of EVs and ethanol.”

Reflecting on Drake’s presentation and his own concerns about EPA modeling, Vander Griend says, “I believe we can show how a clean, high-octane fuel can reduce as much carbon per year as a high rate of adoption for EV’s over the next 25 to 30 years. I do think that, besides getting a good regulatory pathway implemented, we need to have a means of correcting EPA’s models and maybe have EPA use a little common sense. There are plenty of pro-EV folks at EPA, but some of the past rulemakings by EPA clearly show petroleum gets the benefits while ethanol is devalued.”

Drake says, for now, one of the most effective ways for consumers and the ethanol industry to counter the influence of Big Oil and flawed EPA rulemaking is to support retailers with blender pumps offering mid-level ethanol blends today, like NuVu Fuels in Ionia, Michigan, which also has two EV charging stations on site. “We can already see what the future might look like,” he says. “It could be a lot like that neighborhood station back home in Ionia, with higher ethanol blends and EV charging all in one place.”

------

Next Generation Fuels Act of 2021 Introduced in August

In late August, Rep. Cheri Bustos, D-Ill., introduced the Next Generation Fuels Act of 2021, a bill that, in part, aims to establish a new high-octane, low-carbon fuel standard. Bustos introduced similar legislation in 2020. The legislation would require automakers to manufacture vehicles for fuels with a 95 RON or higher by 2026; and a 98 RON or higher by 2031. It would require gasoline retailers to meet corresponding requirements with compatible dispensing equipment by 2026 and 2031, respectively.

The Next Generation Fuels Act would also require automobile manufacturers to design and warranty their vehicles for use with higher blends—25% by 2026 and 30% by 2031. Under the legislation, the octane used in the fuel must reduce greenhouse gas emissions by a minimum of 40 percent when compared to a 2021 baseline. And U.S. Department of Energy’s GREET model would be used to determine lifecycle emissions of the fuels.

Notably, the bill includes provisions that would set a limit on aromatics in gasoline, and ensure that all ethanol blends receive the same Reid vapor pressure (RVP) treatment as E10.

Advertisement

Advertisement

------

Author: Melissa Anderson

Contact: editor@bbiinternational.com

Advertisement

Advertisement

Related Stories

The U.S. EPA on July 8 hosted virtual public hearing to gather input on the agency’s recently released proposed rule to set 2026 and 2027 RFS RVOs. Members of the biofuel industry were among those to offer testimony during the event.

The U.S. exported 31,160.5 metric tons of biodiesel and biodiesel blends of B30 and greater in May, according to data released by the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service on July 3. Biodiesel imports were 2,226.2 metric tons for the month.

The USDA’s Risk Management Agency is implementing multiple changes to the Camelina pilot insurance program for the 2026 and succeeding crop years. The changes will expand coverage options and provide greater flexibility for producers.

President Trump on July 4 signed the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act.” The legislation extends and updates the 45Z credit and revives a tax credit benefiting small biodiesel producers but repeals several other bioenergy-related tax incentives.

CARB on June 27 announced amendments to the state’s LCFS regulations will take effect beginning on July 1. The amended regulations were approved by the agency in November 2024, but implementation was delayed due to regulatory clarity issues.

Upcoming Events