Probing the FSMA rule

PHOTO: INTERSYSTEMS INC.

November 16, 2015

BY Susanne Retka Schill

The final rule for the Food Safety Modernization Act came out in September, starting the clock for compliance deadlines that phase in the comprehensive new rule. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration calls it the most sweeping reform of food safety laws in more than 70 years. And, though medicated feed has been regulated for years, the entire supply chain of the feed industry will now be regulated by the FDA through FSMA.

The biggest change is a shift in emphasis, from a system that responded to problems (think product recalls) to one that requires facilities to adopt current good manufacturing practices (CGMPs), evaluate risks, and create a preventive control plan for those hazards, where deemed necessary. And, as with every regulation, the new rule comes with recordkeeping requirements.

A working group of 10 ethanol industry experts has been digesting the details of the FSMA final rule to pin down just what producers will need to do to insure distillers grains and corn oil bound for feed are in compliance. Kelly Davis, director of regulatory affairs at the Renewable Fuels Association and a member of that working group, says the CGMPs are going to be pretty well covered by existing standard operating procedures (SOPs). Examples are shown in the accompanying illustration. The bigger challenge for the industry lies in the second part of the rule. “The hazard analysis is where most of us will spend our time,” Davis says.

Defining CGMPs industry wide and identifying hazards that need controls will be no small task. Recognizing that, the FDA created a public/private partnership in 2011, enlisting the aid of state and federal agencies, land grant universities and industry associations in a Food Safety Preventive Controls Alliance. The ethanol working group, one of many subgroups in the alliance, is writing a sample food safety plan for the ethanol industry. The plan will provide an example for use in training sessions, showing what the CGMPs, hazard analysis and preventive controls might look like.

The example safety plan is just that, an example, explains David Fairfield, vice president of the National Grain and Feed Association and chairman of the animal food subcommittee of the alliance. “FDA has the expectation that each facility will develop a plan that is unique to its operation.” Other committees within the alliance are working on hazard guidance and curriculum development. The animal food curriculum for FSMA implementation is likely to be a 20-hour course, Fairfield says. “It will be robust.”

All the materials will be available free on the alliance website, and courses will be scheduled once the curriculum is finished and approved by FDA. “Completion of this training will be one way to become a qualified individual,” he adds. The rule says each feed manufacturing facility must have a written food safety plan prepared by a preventive control qualified individual and, even though the rule says an individual can be qualified through job experience, as the FDA commentary accompanying the rule says, those qualifications may be questioned if the plan is not implemented effectively. Also, the supervising qualified individual does not have to be an employee.

The alliance’s goal is to have the curriculum in place by May, Fairfield says, admitting that may be an ambitious target. The ethanol working group hopes to have its sample ethanol plant food safety plan written by February. Charles Hurburgh, director of Iowa State University’s grain quality initiative and a member of the food safety alliance, reports that ISU is working toward becoming an FSMA training center, and he’s anticipating that among the offerings will be an ethanol-industry-specific training course.

The compliance deadlines are staggered, beginning in September. The current CGMPs need to be in place first, followed by preventive controls one year later. The very largest companies, with more than 500 employees, need to have their CGMPs in place by September 2016. The next tier of compliance, which will include most ethanol producers, is required to have CGMPs in place by the end of 2017 and preventive controls defined by the end of 2018. Very small companies, with annual sales under $2.5 million, have three and four years to comply with FSMA’s two parts. Davis cautions, however, that although compliance dates might give many ethanol producers another year or two, market dynamics will be at play. “At this particular juncture, there really isn’t any particular reason to delay compliance,” she says. “I would hate to see small producers get overshadowed.”

Hazard Analysis

While CGMPs may not be a big hurdle, the hazard analysis is raising concern. Two hazards are obvious—mycotoxins and sulfur—but ethanol producers will soon be reviewing all their processing aids to evaluate other potential hazards, and devise preventive controls, if needed. Speaking in an Ethanol Producer Magazine webinar, Richard Coulter, senior vice president for scientific and regulatory affairs at Phibro Animal Health Corp., explains that for processing aids “it might be as simple as, if I follow the instructions for use at the approved label rate, what residues are likely to result from that?”

Sulfur-containing cleaning compounds, as an example, can be used at different levels, some of which might potentially carry through to the coproduct, requiring a preventive control to be sure safe limits aren’t exceeded. “There might be other processing aids that may be more chemically noxious that require more monitoring, if that’s what the hazard analysis show. Or, if the hazard analysis shows them essentially to be innocuous because of their concentration or the chemical nature, another approach may be appropriate.”

He adds that any processing aids used, be they chemicals for water treatment or antimicrobials or natural aids like enzymes or yeasts, must comply legally by either conforming to an AAFCO definition, having GRAS status, or being an approved food additive. GRAS status—generally regarded as safe—is the most common path used for products in the ethanol industry. Very few feed industry processing aids have gone through the food additive approval process, but there is a long list of feed definitions maintained by the American Association of Feed Control Officers.

Mycotoxins are expected to be the most significant hazard that shows up on ethanol plants’ food safety plans. They are a well-known issue that the industry watches for when growing conditions are favorable in the corn crop, as the toxins are concentrated in the distillers grains.

Erin Bowers, postdoctoral associate in the grain quality group at Iowa State University, explains corn is susceptible to mycotoxins when favorable weather conditions occur, especially during grain fill. There are four of interest. Aflatoxins occur in hot, dry conditions, which means they can be problematic in drought years in parts of the Corn Belt and even more frequently in southern corn crops. Vomitoxin (deoxynivalenol) and zearalenone show up in cool, wet conditions and fumonisin is a more prevalent risk in corn grown in conditions in the middle of those extremes.

“At least one type of mycotoxin at every facility is likely to be significant and need preventive controls,” she says, adding that “the risk may differ by year.” FDA has guidance levels for mycotoxins in corn that differ by the type of toxin, as well as the species consuming the feed. Beef cattle, for instance, can tolerate up to 300 parts per billion (ppb) of aflatoxin, while dairy cattle can only tolerate 20 ppb since the toxin can pass into milk and enter the human food supply.

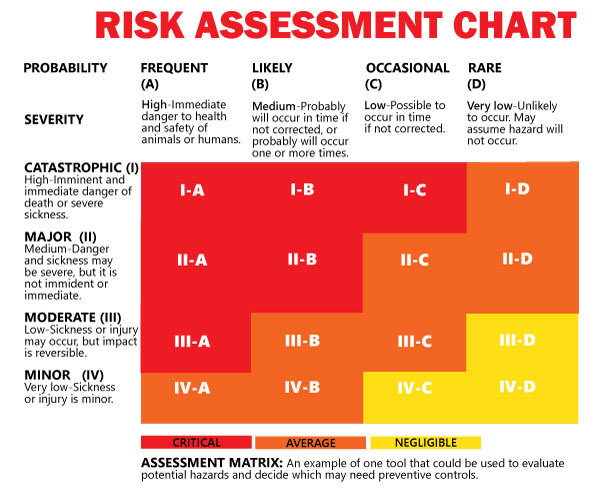

“No particular management strategy or hazard classification strategy is being mandated by FDA,” Bowers says. “It is important for each facility to have a strategy for incoming grain and it would be wise to have this documented.” The accompanying table shows a risk assessment matrix—one example of a tool that could be used by ethanol plants as they assess their hazards and prepare their food safety plans.

The place to control mycotoxins is during grain receiving, she adds, and there will be more than one acceptable strategy for monitoring incoming grain through sampling and testing. Under the FSMA rule, plants will need to validate their strategy through monitoring outgoing coproducts, creating a response plan for any coproducts that don’t meet specs. “All of these strategies, protocols and test results should be documented and readily available. They could be requested at an inspection,” she adds.

Questions Ahead

DDGS buyers have another challenge. The final FSMA rule includes a more fully developed section on the supply chain than appeared in the earlier supplemental to the proposed rule. One element of the new rule, for example, is that feed manufacturers must purchase from approved suppliers. At the same time, the rule apparently tries to avoid duplication of efforts by saying if one party along the supply chain has preventive controls in place for a particular hazard, the steps before or after, don’t have to. How will these features of FSMA be implemented?

Feed manufacturers are also being asked to prove their suppliers have adequate food safety plans in place that are being followed. That implies a feed safety auditing system that needs to become more widely adopted. The American Feed Industry Association has a Safe Feed/Safe Food Certification Program in place that is administered by the Safe Quality Food Institute. The National Grain and Feed Association has a feed quality assurance training program. Both of these programs are likely to see adjustments as it becomes clearer what FSMA requires.

How the supply chain requirements in FSMA’s final rule play out for the ethanol industry will unfold in the months, and probably years, ahead. Questions abound on many fronts. Basing CGMPs on SOPs sounds simple enough, but what happens with those areas in ethanol plant operations where there’s a wide diversity of approaches from plant to plant? Hazard analysis is not entirely new and many plants have individuals with training in FDA’s hazard analysis and critical control points system, but are they sufficiently qualified? Will ethanol plants have to add a position to handle the food safety plans, or will it ultimately dovetail into safety and environmental compliance requirements? Will capital projects be required to comply with potential hazards like preventing bird contamination in grains buildings?

There are no answers to those questions yet and, no doubt, many more will arise as the ethanol industry probes deeper into the FSMA rule.

Author: Susanne Retka Schill

Senior Editor, Ethanol Producer Magazine

701-738-4922

sretkaschill@bbiinternational.com

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Related Stories

President Trump on July 4 signed the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act.” The legislation extends and updates the 45Z credit and revives a tax credit benefiting small biodiesel producers but repeals several other bioenergy-related tax incentives.

CARB on June 27 announced amendments to the state’s LCFS regulations will take effect beginning on July 1. The amended regulations were approved by the agency in November 2024, but implementation was delayed due to regulatory clarity issues.

SAF Magazine and the Commercial Aviation Alternative Fuels Initiative announced the preliminary agenda for the North American SAF Conference and Expo, being held Sept. 22-24 at the Minneapolis Convention Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Saipem has been awarded an EPC contract by Enilive for the expansion of the company’s biorefinery in Porto Marghera, near Venice. The project will boost total nameplate capacity and enable the production of SAF.

Global digital shipbuilder Incat Crowther announced on June 11 the company has been commissioned by Los Angeles operator Catalina Express to design a new low-emission, renewable diesel-powered passenger ferry.

Upcoming Events