Remaining On Track

PHOTO: THE GREENBRIER COMPANIES

October 7, 2021

BY Holly Jessen

The phrase train wreck can be used to describe an accident involving a train, of course, but also anything from a relationship gone bad to a political crisis. In fact, the second definition of train wreck is something that is “an utter disaster or mess: a disastrous calamity or source of trouble,” according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary.

“It’s used a lot and that’s because there are few things that are more catastrophic,” says Chuck Leonard, principal and founder of Rail Safe Training Inc., which offers track inspections as well as onsite and online training for the ethanol and other industries.

Rail transportation is a significant part of day-to-day operations for most of the ethanol industry, says Kelly Davis, vice president of technical and regulatory affairs for the Renewable Fuels Association, which also offers rail-related training. Specifically for ethanol plants located on a rail line, an average of three dozen railcars get moved daily, including receiving materials as well as shipping out ethanol and distillers grains. In all, about 70 percent of ethanol is transported to the marketplace via rail.

“We are the largest hazmat moving on the rail,” Davis says. “We are, by far, shipping more hazardous material as ethanol than any other flammable, including crude oil.”

Advertisement

Regulatory Compliance, Training

Since December 2010, the RFA has held 355 ethanol safety training events with more than 14,000 participants, says Missy Ruff, director of safety and technical programs for RFA. Due to Covid, the organization has now held 31 of those training sessions online. The shift actually allowed more people to take advantage of the training. “Instead of being in one location, training one town and maybe some people from the outskirts coming in, we’re getting people from other countries attending,” she says, adding that, to-date, RFA has trained people from a total of 29 countries.

In addition to training, the RFA has a 33-page manual called Best Practices for Rail Transport of Ethanol. It can be found at RFA’s website under Resources/Producers/Safety Information. The manual has never been restricted to RFA members only, Davis says.

One of the things the manual outlines is the importance of regulatory compliance. Shippers, such as those in the ethanol industry, risk fines and penalties if they are non-complaint. The manual lists some of the most common regulatory violations, the highest fine for which is $10,000 for leaking product. The lowest fine on the list is $1,000 for a placard that isn’t visible, located or displayed properly or in a deteriorated condition. Another thing for producers to pay extremely close attention to is the shipper checklist, Davis says, which must be used for every carload. “The Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) is definitely visiting our plant sites routinely to assure that our shippers are following these very strict regulations,” she says.

Leonard of Rail Safe Training, a past locomotive engineer, puts it another way. He believes private industries with onsite railroad tracks have a compliance problem. In visits to places that load flammable liquids, including but not limited to the ethanol industry, the company has observed plenty of issues. “Virtually none of them have 100 percent compliance with FRA mandated procedures,” he says.

He believes there’s a strong need for more railroad safety training among private industries, including ethanol. Looking at just accidents suffered by Class I railroads, the seven railroads with operating revenues of $490 million or more according to FRA, Leonard says data shows one in six of those accidents happen on private industry land. “Which is actually a staggering number when you consider that they probably spend less than 1 percent of their time servicing industries,” he says. “… It’s exponentially larger than it should be.”

The one in six number doesn’t include incidents suffered by smaller Class II and Class III railroads, which, he reasons, spend more time on private industry land and therefore likely have even more accidents there. Then there’s the rail-related accidents that happen to private industry employees or involve private industry equipment. “I’d say it’s probably 20 times as dangerous to go in a private facility as it is to stay within the railroad,” he says, adding that’s his estimation based on anecdotal evidence.

He pointed to the tank car manway as one example of an area where more training is needed. There’s a gasket under the hatch cover which keeps liquid from escaping. “There’s been a pretty high incidence of those found to be leaking by the FRA,” he says.

Leonard listed off some key things to keep in mind when dealing with manway covers. First off, the bolts used to keep it shut must be tightened in a specific pattern, not just around in a circle. Secondly, spark-proof wrenches must be used. Finally, it’s important to pay attention to the required amount of torque, which depends on the various gasket materials. “Quite often we find a guy up there with an air wench that’s just putting them on as tight as he possibly can,” he says.

Another issue Leonard sees frequently on private industry land is cars that aren’t properly secured with a handbrake. An approximately 130-ton tank car may not seem like it’s going to roll anywhere when parked, but a thunderstorm can prove that assumption wrong. “A 60 mile an hour wind can move a rail car,” he says, adding that the resulting accident has the potential to cause a lot of damage.

Maintenance in Mind

Track maintenance is another thing Leonard sees as an area of concern. Ethanol plants that had brand new tracks installed when the facility was built now face the challenge of aging infrastructure, including rail lines.

Repairing a railroad track can be relatively inexpensive, he says. Sometimes all that’s needed is a load of crushed rock and the labor to put it into place. Unfortunately, he’s seen examples of this type of maintenance being ignored. The tracks may pass inspection, he says, but more proactive maintenance can increase longevity and help avoid accidents.

“There are very few things that are more costly to neglect than a railroad track,” he says. “So many places wait until they have cars on their side and that can run into the tens if not hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

Davis pointed to maintenance issues related to tank cars. In the ethanol industry, the producer typically leases tank cars rather than owning them outright. That means the tank car owner is the one responsible for maintenance and repair. “That quality management aspect has been one of the latest FRA activities out there,” she says. “They want the owners to understand their responsibility.”

Another layer is that not just anybody is allowed to make repairs to tank cars. “That’s probably one of the growing things in the industry,” she says. “Our guys in the field, even though they might be able to fix the car, they aren’t allowed to because you have to send it to a certified shop.”

Out With 111, In With 117

Ethanol producers are also facing a May 1, 2023, deadline to update the remaining legacy DOT-111 tank cars to DOT-117 tank cars, as required by the 2015 Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act. CPC-1232 tank cars, a voluntary standard adopted by the industry prior to the FAST Act, have different deadlines. Non-jacketed CPC-1232 tank cars must be updated to the 117s by July 1, 2023, while jacketed CPC-1232 tank cars have until May 1, 2025. “For the most part, they’re thicker cars or they have safety features that the DOT-111s don’t,” says John Byrne, vice chairman of the Committee on Tank Cars for the Railway Supply Institute (RSI). “Some of them are very close to the 117s.”

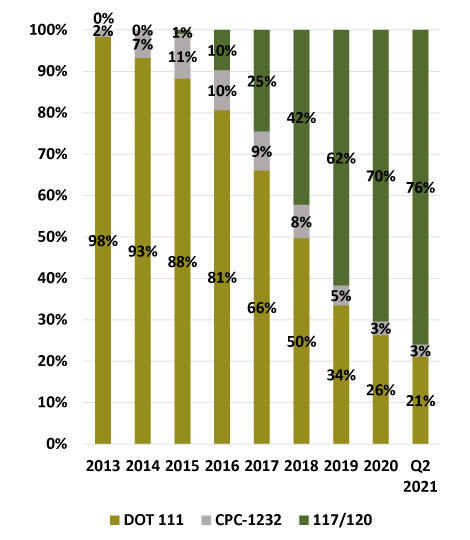

While there was concern at one point about the rail car industry’s ability to build enough tank cars fast enough to meet the deadline, that didn’t turn out to be the case. One thing that helped is that about half the 111 tank cars have been retrofitted to 117 standards while the other half are new builds. “We’re about 75 percent turned on the cars,” Davis says. “I’m very comfortable with that progress.”

That’s good news, considering there’s zero wiggle room in the deadline. Any producer that still has 111s in service after the deadlines will be out of luck. “You won’t be able to ship by rail,” she says. “There’s no loophole on the rail. They won’t even pick it up.”

Byrne agrees things look good. With 7,000 new or retrofitted 117 tank cars needed before the deadline, the rail car industry definitely has the capacity to meet the demand despite the fact that fewer retrofits and new builds are currently being completed due to the pandemic.

He highlighted RSI data that shows the number of retrofits peaked at 750 cars retrofitted in October 2018 while only 32 were completed this July. For new builds, the peak was in August 2015 at 1,919 new FAST-Act compliant tank cars built. Compare that to this June when a total of 262 new tank cars came off the production line. That puts the average number of new 117s built in the first six months of the year at 208 per month. “We have the potential to produce a lot of cars, so the capability isn’t an issue,” he says.

Something else to consider is that as of the second quarter of this year, there were a total of 2,825 idle 117 tank cars, according to information from the Association of American Railroads. These tank cars are probably leased by crude oil shippers that don’t currently need them due to declining demand, Byrne says, adding that when they come off lease they can be moved into ethanol service. “A lot of that’s driven by change in demand, surplus of cars,” he says. “We’re not going to produce a lot of cars when you still have cars sitting in storage. I think we’re tracking pretty well.”

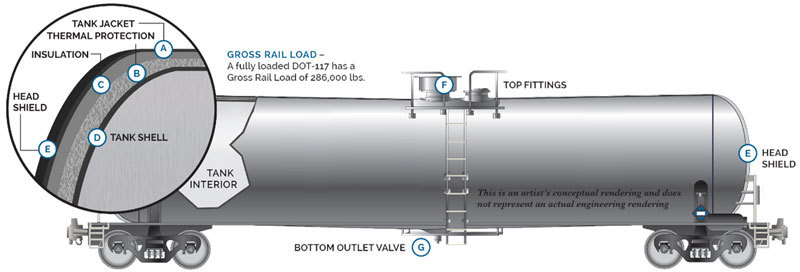

The 111 tank cars were designed before ethanol was transported in large unit trains. Those tank cars are “plain-Jane, bare tank shell” cars with very few safety features, Byrne says. The 117 cars take the same bare shell and add on multiple new safety features.

The first is a layer of ceramic for thermal protection to help reduce heat transfer to the tank in the event of a fire. By federal law, the material must prevent the car from exploding for 100 minutes, he says. The 117 cars also have a 1/2 inch steel head shield, which protects a car from punctures. “Years ago, one of the most common tank shell breaches would be a head puncture caused by another car’s coupler or something like that,” Byrne says. “The half inch head shield reduces the probability that you’re going to experience a puncture given a derailment.”

Next up is the bottom outlet valve, which includes a disengaging handle to prevent the valve from opening in a derailment. The top fittings protection prevents a release at the top of the tank car, in the event of an accident.

All 117 cars, whether newly built or retrofitted, have the same safety features. The only difference is that retrofitted 117s have a 7/16 inch tank shell while the newly built 117s have a 9/16 inch tank shell, Byrne says. Both tank cars are complaint with the FAST Act, however.

Data comparing 111s to 117s shows a marked improvement, he says. The numbers for conditional probability of release (CPR), a statistical analysis of the probability of a tank car releasing more than 100 gallons of product, show 111 tank cars have about a 20 percent chance of a spill in an FRA-reportable derailment. The new 117 tank cars, however, have reduced that probability of product release by 85 percent to a CPR of only 3 percent.

The RSI also calculates a yearly fleet average CPR, Byrne says. For the 2013 fleet, the average CPR was almost 20 percent. The numbers in 2020, with a lot of 117s in service, showed a significant decrease in CPR. “When we compare the last full year, 2020, it’s basically gone down to 8 percent, or a 60 percent reduction in the probability that a car will lose product,” he says.

The RSI isn’t the only organization noticing safety improvements with more 117s in service. Davis points to a derailment involving ethanol tank cars in Fort Worth, Texas, in 2019, in which the older 111 tank cars were the only ones that spilled product. “We definitely feel better about the 117s,” she says.

In fact, as a result of that accident and another one in 2020 the National Transportation Safety Board asked RFA to update its best practices manual. The RFA announced it had done that in June, encouraging ethanol producers that are able to rearrange their tank cars to put the older tank cars in the back. “In the last two accidents that happened they noticed that when we’re shipping mixtures of 117 cars and 111 cars, they want the 111 cars toward the rear of the train, Davis says. “Because in a long unit train when cars derail they are usually toward the front of the train.”

Author: Holly Jessen

Contact: editor@bbiinternational.com

Advertisement

Related Stories

Keolis Commuter Services, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority’s operations and maintenance partner for the Commuter Rail, has launched an alternative fuel pilot utilizing renewable diesel for some locomotives.

Virgin Australia and Boeing on May 22 released a report by Pollination on the challenges and opportunities of an International Book and Claim system for sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) accounting.

The biodiesel industry has been facing turbulence, but the release of long-overdue policy could course-correct.

The U.S. House of Representatives early on May 22 narrowly passed a reconciliation bill that includes provisions updating and extending the 45Z clean fuel production tax credit. The bill, H.R. 1, will now be considered by the U.S. Senate.

U.S. EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin on May 21 stressed the agency is working “as fast as humanly possible” to finalize a rulemaking setting 2026 RFS RVOs during a hearing held by the U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works.

Upcoming Events