Tuning up the Decanter Centrifuge

PHOTO: ALFA LAVAL

February 14, 2013

BY Susanne Retka Schill

There’s an apt analogy for centrifuge maintenance in ethanol plants to how different people view their cars. Some follow the recommended maintenance routine and get the oil changed at the appointed time, regularly swap out windshield wipers and replace tires as they near the end of the expected lifespan. Others push the oil changes out to the maximum, only change the wipers when they begin to come apart and wait to change tires until the steel cords are beginning to show.

Chris Fell, market unit manager in separation products at Alfa Laval Inc., says he participated in a study over a decade ago that compared these two approaches to maintenance at an ethanol plant. For three years, the cost of preventative maintenance on one set of centrifuges was compared to a second set for which repairs were done as needed. “The cost for the preventative maintenance averaged 28 percent less than running on a reactive maintenance schedule,” he says.

A challenge for the ethanol industry is that some maintenance schedules follow set intervals while others are site specific. Fell recommends that ethanol producers benchmark wear characteristics over the first few years of operation and use this data to plan future inspection and maintenance schedules. “Some people will plan that for every 18 months where others can go 40 months,” he says. “Knowing that in advance is critical, and not making the assumption that you leave something go for three years and you’ll be OK.”

The wear characteristics are determined by how much abrasive sand and grit is in the process, Fell says. “It’s a combination of factors. In the ethanol industry, sand content varies depending on where the corn is harvested. Another factor is process water and how it is filtered. A third factor, particularly in older plants, is the re-use of floor washings from a sump back into the process.”

Advertisement

Plants that experience high-wear characteristics, he adds, should consider using one or more forms of erosion protection specifically developed to extend maintenance intervals and protect the equipment. One such technique is a tile system rather than the less-durable hard surfacing on the edges of the of scroll conveyer. “The tiles are expensive as a component,” Fell says. “But in the ethanol industry, we find very little wear on tile assemblies.”

Planning for the big maintenance projects is built around recommended routine tasks, such as greasing the bearings during a brief shutdown every two weeks and replacing the gear box oil every six months. Dell Hummel, Alfa Laval sales manager for separation equipment in the U.S. ethanol, starch and sugar markets, points out that a plant that operates 24/7 runs roughly 8,000 hours in a year. Referring to the car analogy, he says, “Every once in a while you have to perform tune-ups, that’s where bearing changes—every 8,000 hours for conveyer bearings and every 16,000 hours for main bearings—come in.”

Fine-Tuning Operations

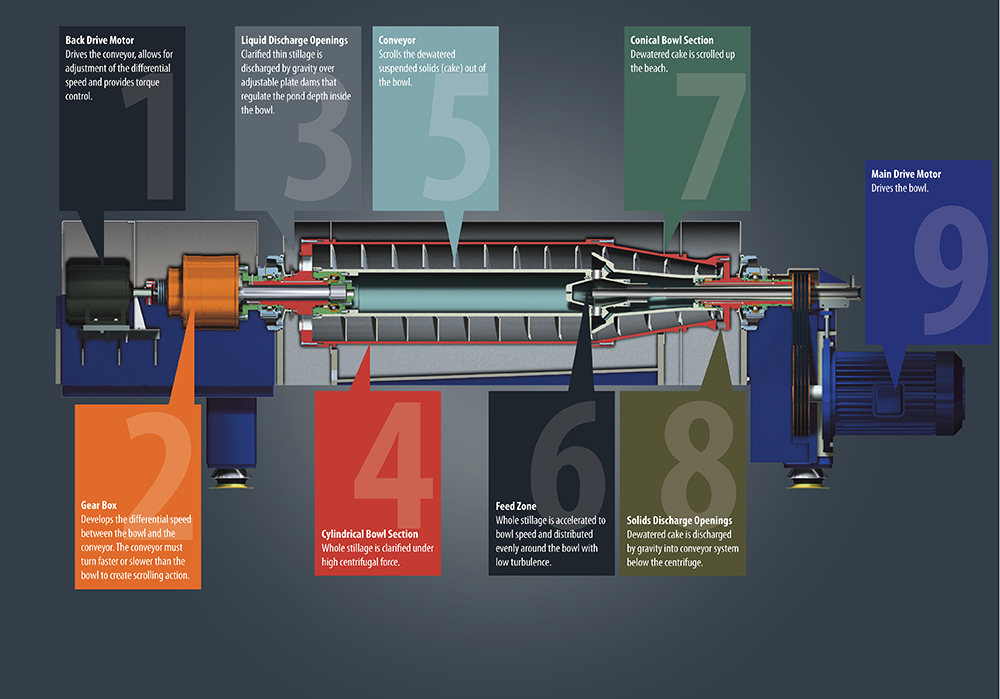

Hummel, who serves as a decanter specialist supporting the global ethanol market, explains how fine-tuning centrifuge operation affects the front end of the process, as well as the efficiency of the evaporators and dryers. The function of the decanter centrifuge is to dewater whole stillage, which is the water, spent grains and yeast remaining after ethanol is distilled.

The centrifuge separates the suspended solids from the thin stillage (also called centrate) that contains primarily dissolved solids. To use another analogy, the suspended solids are like sand that settles to the bottom of a bucket of water, whereas dissolved solids in the thin stillage are like sugar granules in water. The suspended solids are conveyed out of the conical section of the centrifuge bowl and become the wet cake that heads to the dryers. The thin stillage is decanted off the other end of the centrifuge bowl. Generally, about a third of the thin stillage becomes backset and is sent to the front end of the process to become part of the makeup water for the next batch of mash. The rest of the thin stillage is concentrated in the evaporators and applied to the wet cake, becoming the solubles in distillers dried grains with solubles.

Advertisement

The challenge for centrifuge operations is to find the right balance between getting the optimal amount of water out of the wet cake to reduce the load on the dryers while maximizing the clarity of the thin stillage to minimize fouling in the evaporators. It is best to keep the level of suspended solids remaining in the thin stillage at about 1 to 2 percent, Hummel says. Too many fine solids tend to build up in the process and, in the portion used as backset, those fine solids that are not fermentable take up valuable space in the fermenter and reduce yields.

Two main variables impact separation efficiency. “The higher the flow rate, the lower the separation efficiency,” Hummel says. The other main adjustment is the differential speed between the bowl and the conveyer. The bowl uses centrifugal force to remove the suspended solids while the conveyer, running either slower or faster than the bowl, creates a scrolling action that moves the solids out of the bowl. “If you move the solids out quickly they come out wetter,” Hummel explains. “Because you move them out quicker, there’s not as much solids build-up in the bowl, so you end up with a cleaner thin stillage.” Conversely, a lower differential speed moves solids out more slowly giving them more retention time in the bowl and the solids come out drier, but there is more potential for carryover to the thin stillage.

In some centrifuge designs, another adjustment can be made to the dams that control the depth of the liquid left in the centrifuge pond as the liquids decant off. “If you have a traditional decanter, the deeper you make the pond, the cleaner you’ll make the thin stillage but the wetter the cake,” Hummel says. Alfa Laval’s centrifuge design eliminates that adjustment, he adds. “The machine we use for the ethanol industry has a baffled feed zone, which allows us to run with a deep pond to make clean thin stillage, but it blocks the pond from getting to the conical portion of the machine, so we can still make a dry cake.”

Venting is another critical issue that can be overlooked, Hummel continues. “This is a hot process—the feed material is going in 20 or 30 degrees below boiling for water. You get vapors and steam inside the machine and you can get vapor and steam coming back from the dryer through the conveyer system or from the thin stillage tanks coming back up to the decanters.” If not vented, the housing around the bowl fills with steam and makes the bearings run hot, or if pressure begins to build, can even force steam into the bearings. “Once you do that, you reduce the bearing life and could potentially have bearing failures,” he explains. “It is a critical thing.” Utilizing a slight vacuum will help vent the steam off the machines but it is important to ensure the vacuum be equal on both ends of the machine so there is no interference with the movement of the material. This helps avoid a buildup of solids in the centrifuge housing.

Many factors play into the decisions behind how to operate the centrifuges. Some plants, of course, are located near cattle lots that prefer wet cake, thus they don’t have to worry about optimizing the dryers. Most plant operators, though, are well aware that dryers are the biggest energy users in the plant. Yet, while the temptation is to keep the cake as dry as possible, the resulting thin stillage is the bigger issue, Hummel warns. “It’s more of a disruption to let the thin stillage get too dirty. If the evaporator fouls, a shutdown is required in order to clean and that’s not an easy job. If too many unfermentable solids are returned to the fermenter, ethanol production is reduced. Performing planned, predictive maintenance and regular process tuning is an important factor in optimizing the complete process.”

Author: Susanne Retka Schill

Contributions Editor, Ethanol Producer Magazine

701-738-4922

sretkaschill@bbiinternational.com

Related Stories

SAF Magazine and the Commercial Aviation Alternative Fuels Initiative announced the preliminary agenda for the North American SAF Conference and Expo, being held Sept. 22-24 at the Minneapolis Convention Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Saipem has been awarded an EPC contract by Enilive for the expansion of the company’s biorefinery in Porto Marghera, near Venice. The project will boost total nameplate capacity and enable the production of SAF.

Global digital shipbuilder Incat Crowther announced on June 11 the company has been commissioned by Los Angeles operator Catalina Express to design a new low-emission, renewable diesel-powered passenger ferry.

International Air Transport Association has announced the release of the Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) Matchmaker platform, to facilitate SAF procurement between airlines and SAF producers by matching requests for SAF supply with offers.

Alfanar on June 20 officially opened its new office in London, further reaffirming its continued investment in the U.K. The company is developing Lighthouse Green Fuels, a U.K.-based SAF project that is expected to be complete in 2029.

Upcoming Events