Riding the Performance Curve

May 18, 2015

BY Susanne Retka Schill

A healthy cash balance is a nice problem to have, though it does present its own challenge. The questions ethanol company boards and management face are simple, but crucial to the long-term viability of their businesses: How much working capital needs to be preserved? What level should be reinvested in the business? How much should be paid out to investors?

Ethanol Producer Magazine turned to three ethanol industry financial advisors––Christianson & Associates PLLP, Ascendant Partners Inc. and K-Coe Isom––to see what lessons they are sharing with boards and managers as they meet in strategic planning sessions.

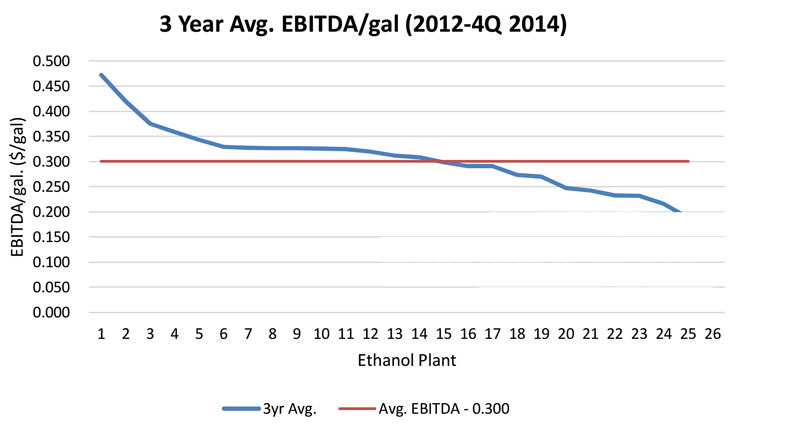

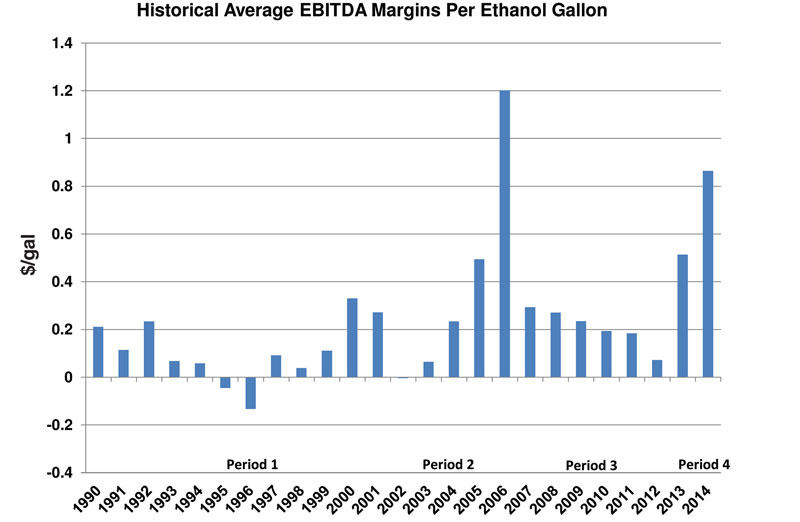

“EBITDA per gallon is a good place to start,” says Mark Warren, partner and chief financial officer at Ascendant Partners. It encompasses both revenue, how well a plant buys corn and sells ethanol and distillers grain, and operating performance and efficiency. “The net result of those dynamics, by definition, will result in your performance on EBITDA—revenue less cost of goods sold, less operating expenses—gets you earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization.” The Figure 1 bar chart for EBITDA per gallon since 1990 is calculated using formula-based assumptions and multiple commodity prices. It illustrates the wide swings the U.S. ethanol industry has seen since its early years. It is critical for managers to know where their plants fall on the performance curve, Warren says.

Creating another gauge for comparison, Warren has taken the financials from 26 publicly traded ethanol producers and charted in Figure 2 the average EBITDA per gallon over the past three years, which includes some of the leanest and best operating margins seen in the ethanol industry. “The graphic shows the variable from the best to the worst,” he says, pointing out that it includes a range of plant sizes, primarily located in the Midwest but including destination plants. The average EBITDA per gallon for that group is 30 cents per gallon, ranging from a top performer of nearly 50 cents per gallon, to a low of 15 cents.

The chart of publicly traded companies mirrors the pattern seen with plants in the Ascendant benchmarking group, combined with facilities the company has assisted in selling over the years. “You’ll see a swing of 70 to 80 cents a gallon on an EBITDA basis from a top performer to a marginal producer,” Warren says. That goes from a high three-year average of 50 cents per gallon to a low of negative 20 cents per gallon. The 2012 drought dominated the first year of his analysis, when producers struggled with tight corn supplies and high prices. “Everybody had to experience that drought, and it’s telling in terms of who were able to perform better and keep their heads above water and who lost significant amounts of money,” Warren says. Good years like the last one are easier to operate in, but margin swings will continue. “We can expect volatility going forward. That’s part of it, when you’re dealing a commodity-in and commodity-out enterprise.”

Digging into the performance is the next step, he continues, to evaluate why the plant is positioned high or low on the curve. “Is it a market thing? A plant thing? A technology thing? Is it a combination?” he asks. “And then, what kind of things can you do to improve your position?” Each plant is different, he adds. Some have issues that are difficult to overcome, such as a poor location relative to ethanol or distillers marketing, or a local corn basis that has been permanently restructured. As new technologies are adopted industry-wide, it puts pressure on all to keep driving costs down and efficiencies up. It is imperative, he stresses, that plants keep up, lest they become the marginal producer with a low or negative EBITDA per gallon, putting it in jeopardy whenever margins are tight. He adds that there is a high risk for that to happen more often, now that ethanol capacity appears to be outgrowing demand.

“It’s a continuous process and there’s continual innovation that is occurring in the ethanol space, which is great for everybody involved. That puts more onus on the board and management to make very good, informed decisions on what they’re going to do to improve the asset and underlying performance of that plant, which ultimately improves the evaluation of their asset as well,” Warren says. “We had such a good year last year, but we saw a lot of plants distribute a lot of capital coming out of that. I think that was initially great for shareholders but, if we find ourselves in a challenging year, that could have some cash flow implications with these plants which may limit their ability to be as responsive as they need to be to adjust and improve their position on the curve.”

Benchmarking Insights

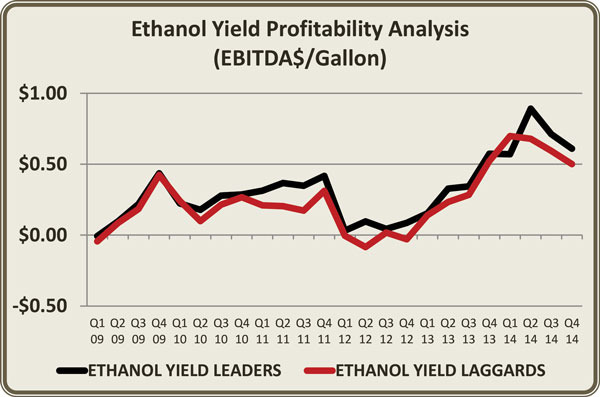

When Christianson & Associates asks boards for their priorities, much emphasis is put on improving ethanol yields, says Connie Lindstrom, benchmarking analyst. She dug into the data to see how well ethanol yield correlates with EBITDA, comparing the EBITDA per gallon from the leaders in ethanol yield—the top 25 percent in yield—from the laggards, the bottom 25 percent. Figure 3 shows the five-year average EBITDA performance in each quarter for the yield leaders in the black line and the laggards in red. “It’s interesting,” she says, “because it shows how little impact it really has whether you’re a leader or laggard in ethanol yield.” In the periods of strong margins, better ethanol yields did translate to higher profitability, she adds, “but it typically isn’t as high as a lot of people think it would be.”

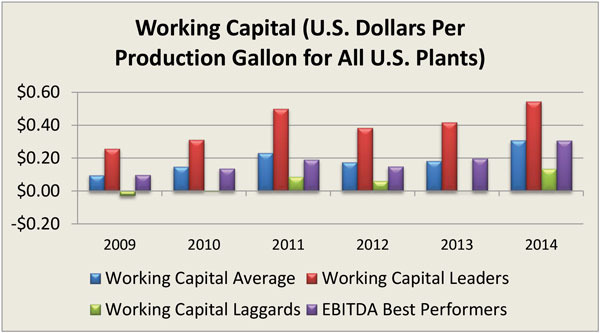

The data also illustrates the situation facing those boards in their strategic planning sessions coming off 2014’s strong margins. Looking at the average financial ratios, found in the Figure 4 table, a current ratio of assets to liabilities hovering around two is considered a healthy number, Lindstrom says. “It indicates there isn’t too much capital sitting around waiting to be utilized.” In 2014, the current ratio rose to 2.46. “That’s definitely a high over the past 10 years even,” she adds. “What that tells us—and what we hear when we go out to the plants—is they’re in a holding pattern. They’re making decisions on what to do with that capital.” That is confirmed in the working capital ratio which has doubled from its five-year low point in 2010 to 31 cents per gallon for 2014.

Other ratios add to the story. Long-term liabilities have dropped from 47 cents per gallon five years ago to 19 cents per gallon after 2014. “The plants have paid down their debts,” Lindstrom says, “but the negative side to that is that some of these older plants that have been producing 10 to 15 years have not been reinvesting.” That is confirmed in looking at the fixed assets ratio, which has stayed pretty stable over time, particularly the past three years. “They haven’t been expanding or putting in new technologies,” Lindstrom adds, “so they’re looking really hard at doing some of these things now.”

To answer the question of how much working capital should be targeted, the average working capital in the benchmarking group was compared to the leaders and laggards for that metric. Then to gain further insight, Lindstrom took a subset of the 10 best performing plants—those with consistently top earnings in every quarter over the past five years—and compared their working capital. Figure 5 shows those 10 EBITDA best performers keep their working capital close to the average. Average working capital, furthermore, is a moving target. “There isn’t a number per se, but there seems to be that ability to not let it pool up too much, but not let it dip down too far either,” she says.

“What that translates to is that they have a policy in place,” Lindstrom explains. “They can distribute [capital] as dividends or they can pay down debt or do some strategic investing. They’ve got a target for all three of those things: Here’s what we’re going to do when we’re squeezed and here’s what we’re going to do when things are better. So, they are reacting more quickly.”

Success Beyond Numbers

As important as the financial performance is, Donna Funk, an accountant and principal with K-Coe Isom, steps back to take a longer view of other factors important to a successful business. “You can have the healthiest balance sheet in the world, but if you don’t have the right other components to your business, you may not stand a chance of success, especially during difficult times,” she says. “It’s those intrinsic values that really can be the differentiating factor in what your ultimate success is.”

In her 20-some years in the business, she’s seeing a shift towards a more relational approach in her own profession and in all sectors she follows. One obvious example is to maintain good relations with employees—both existing and potential future employees. “What do people in the community say about your business, as not only a corporate citizen, but what are your employees saying out there as to what it’s like to work for you?” she asks. Another example would be that interactions with vendors need to go beyond placing orders. Good vendor relations, including with those you don’t currently buy from, can be particularly helpful for learning about and evaluating new technologies. Similarly, regular communications with customers—the buyers of ethanol and coproducts—are important to developing better understanding of each other’s businesses and heading off issues.

Having more than strictly business relations with your banker is important as well, she stresses, and with more than just one person. She has seen an instance where a bank—not a small one, but one that wasn’t a traditional player in the ethanol industry—pulled the line of credit. “It ultimately came down to there weren’t enough people at the bank comfortable with the industry,” Funk recalls. While that doesn’t mean the banker needs to become a best friend, it is wise for plant management and boards to cultivate multiple relationships within their lending institutions, she advises.

“I don’t know that you can say [these intrinsic values] translate directly to the bottom line,” Funk continues, “but I think it definitely can translate into the attitude of people, the willingness of people to do something a little extra for you.” Financial performance numbers are important, she adds, “I would never say they are not, but you’ve got to look beyond the historical numbers reporting and get to those underlying aspects of the business that ultimately do impact your financial results.” It might be difficult to align improved relationships with the bottom line, she says. “But I do think if you ignore all those things, you’d certainly see a negative impact on your financials.”

Author: Susanne Retka Schill

Senior Editor, Ethanol Producer Magazine

sretkaschill@bbiinternational.com

701-738-4922

Advertisement

Advertisement

Related Stories

Keolis Commuter Services, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority’s operations and maintenance partner for the Commuter Rail, has launched an alternative fuel pilot utilizing renewable diesel for some locomotives.

Virgin Australia and Boeing on May 22 released a report by Pollination on the challenges and opportunities of an International Book and Claim system for sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) accounting.

Chevron U.S.A. Inc. on May 15 filed a notice with the Iowa Workforce Development announcing plans to layoff 70 employees at its Ames, Iowa, location by June 18. The company’s Chevron REG subsidiary is headquartered in Ames.

Luxury North Dakota FBO, Overland Aviation—together with leading independent fuel supplier, Avfuel Corp.— on May 19 announced it accepted a 8,000-gallon delivery of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) on May 12.

May 21 marks the official launch of the American Alliance for Biomanufacturing (AAB), a new coalition of industry leaders committed to advancing U.S. leadership in biomanufacturing innovation, competitiveness, and resilience.

Upcoming Events