The Road Ahead for the RFS

October 18, 2022

BY Luke Geiver

Starting in 2023, the Renewable Fuel Standard’s yearly required volumes will no longer be based on the firm statutory instruction of federal law. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, along with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Department of Energy, will be determining—with new formulas not prescribed by Congress—renewable volume obligations, or RVOs. The change marks the first time since the formation of the RFS in 2005 that yearly RVOs will not be determined strictly by legislative instruction.

The EPA was authorized to set annual biofuel blending requirements through 2022. For 2023 and beyond, however, the agency is required to establish volume requirements according to a specific set of alternative factors. Ethanol trade groups emphasize that the RFS is not expiring, but entering a new phase in which the EPA, with support from the USDA and the DOE, has more leeway in its administration of the program. The upcoming “set” rule will be the first annual RVO rulemaking under which the EPA exercises this discretion.

By the time this article is published (or very soon after), the proposed RFS volume obligations for 2023 may be out, thanks to the work of groups like Growth Energy, the Renewable Fuels Association, the Clean Fuels Alliance and others. In late July, Growth announced that its efforts to push the EPA to move forward with determining volume requirements had proven successful. Through a consent decree agreement, the EPA publicly went on the record, agreeing to offer proposed volumes for 2023 by November 16, 2022. That agreement also states that by June 14, 2023, volume requirements under the RFS will be finalized. With the first step of the RFS reset locked in, the question for producers, blenders, renewable identification number (RIN) traders and every other entity impacted by the historic and long-tenured positive influence of the RFS is a big one. What exactly is going to happen?

What Should Happen

Joe Kakesh is the general counsel for Growth and has been heavily involved in working with the EPA to get to this point with the deadlines for 2023 RFS RVOs. Kakesh is no stranger to the workings of Washington or in navigating several of the departments that impact the greater biofuels industry. Prior to joining Growth, he worked in the environmental law sector, gaining experience with the Clean Air Act, RFS and other regulatory programs administered by the EPA, USDA, FDA, DOE and others. According to Kakesh, getting the EPA to set deadlines for deciding on 2023 RVOs was the first win. Now, his team—working in tandem with the other trade groups—will continue to push the EPA to take advantage of the full potential offered by the RFS as it relates to the federal government’s overall climate goals.

“The RFS to date has been one of the most successful clean energy solutions,” Kakesh says. “But it still remains somewhat untapped as a climate solution.”

The 2023 RVOs should reflect the ability of the RFS to become a major tool for the push by the U.S. to reach its climate goals, he says. Because the program deals with renewable fuels and has been around since 2005, it is hard to argue that the RFS is anything but a proven tool that still works well Kakesh believes.

“We should be taking full advantage of renewable fuels through the RFS,” he says. “Farmers and producers are ready now.”

The potential impact of greater—or even firmly set—RVO volumes next year, or in the years after, can make a dent in the carbon reduction efforts of the U.S.

RFA President and CEO Geoff Cooper agrees. During a virtual briefing about the RFS set held by Fuels America in late September, he said a strong set rule can help meet the Biden administration’s decarbonization goals. “We think EPA has an enormous opportunity with this rulemaking process to further decarbonize our nation’s transportation fuels, and ... I want to remind everyone that the RFS is the only statutory program on the books today that requires fuel decarbonization.”

Kakesh says the industry needs to tell the important part of the ethanol story as it connects to the climate goals that will guide U.S. policy across multiple sectors for years to come. The story of ethanol should be about how it provides a robust contribution to lowering greenhouse gas emissions, lowers fuel costs and plays a strong part in the long-term climate strategy of the U.S. According to Kakesh, that storyline is what should happen as the EPA’s decision on 2023 RVOs plays out. But, he points out, there are many factors that impact what ultimately will happen.

The Main Factors

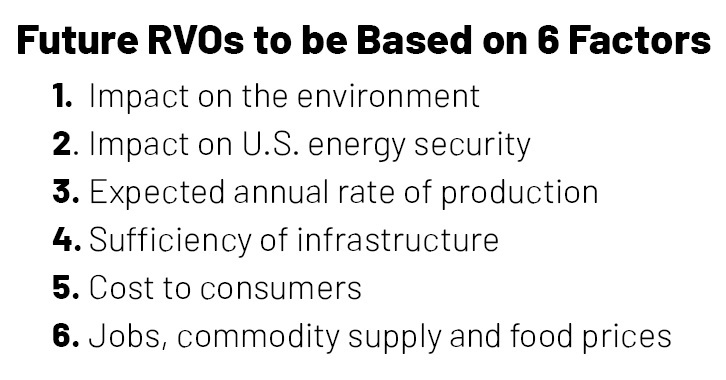

To arrive at significant RVOs through the RFS for 2023 and beyond, the EPA has publicly stated it will utilize six factors to aid in the process. The first factor is the impact of production and use of renewable fuels on the environment, including on air quality, climate change, conversion of wetlands, ecosystems, wildlife habitat, water quality and water supply. The second relates to how a renewable fuel can impact U.S. energy security. The expected annual rate of future commercial production of renewable fuels, including advanced biofuels such as cellulosic or biomass-based diesel, represents the third factor. How renewable fuel impacts U.S. infrastructure, including deliverability of materials, goods and products other than renewable fuel, along with the sufficiency of infrastructure to deliver and use renewable fuel, is the fourth area the EPA will look at. The cost of renewable fuel to consumers is the fifth. And the sixth factor is the impact of renewable fuels on job creation, the price and supply of agricultural commodities, rural economic development and/or food prices.

In addition to those main six factors, the EPA has already stated that it also has “the authority to consider other factors.” The agency has already considered some of those factors, including the intertwined nature of compliance with 2020 to 2022 standards, the size of the carryover RIN bank, how the entirely retroactive nature of the 2020 and 2021 standards—as compared to the partially prospective nature of the 2022 annual and supplemental standards—affects the feasibility of compliance, the supply of qualifying renewable fuels to U.S. consumers, soil quality, and environmental justice.

There is an important element to all of the factors, especially those main six, according to Kakesh.

“The key is that not all six factors are equal,” he says.

The EPA has addressed that important fact. “While the statute (to determine the RVO volumes) requires that EPA base its determination on an analysis of these factors, it does not establish any numeric criteria, require a specific type of analysis (such as quantitative analysis), or provide guidance on how EPA should weigh the various factors.” The department also says that it is not aware of anything in the legislative history of EISA (the Energy and Independence Security Act created in 2007 under President George W. Bush as an expansion of the RFS) that provides authoritative guidance on these issues. With the lack of precedence or past guidance on how the EPA might weigh the factors in making its decisions, the agency says it has “considerable discretion to weigh and balance the various factors.”

Many, including Kakesh, believe the leading factor the EPA will weigh above all others is the environmental benefit of biofuels versus fossil alternatives. for that reason, the decision makers need to see the environmental benefit of ethanol. That starts with using the latest science, modeling or testing, all of which Kakesh says, “show the benefits.” The issue, however, is that the EPA’s latest science on modeling GHG emissions linked to ethanol production hasn’t been updated since 2010. Thankfully, Kakesh says, there has been some work on that front.

Implementing the Latest Science

Although the last time the EPA updated its lifecycle emissions modeling related to ethanol was in 2010, there has been work to bring modern science and testing on the subject into the EPA’s view. In March, EPA hosted a virtual public workshop on biofuel GHG modeling. The purpose of the workshop was to solicit information on the current scientific understanding of GHG modeling of land-based crop biofuels used in the transportation sector, according to the EPA. The meeting shows the interagency connectedness that will come in the 2023 RFS set. Along with the EPA’s Office of Transportation and Air Quality, the USDA and DOE also participated in the workshop.

The purpose of the three-day workshop, which included industry experts talking or giving presentations on a range of subjects, was three-fold. First, the EPA wanted commentary on what sources of data exist and how those data sets can be used to inform the assumptions that drive GHG estimates. Second, EPA wanted to know how it should best characterize the sources of uncertainty associated with quantifying the GHG emissions associated with biofuels. And third, EPA wanted to know what models are available to evaluate the lifecycle GHG emissions of land-based biofuels, and “if those models meet the Clean Air Act requirements for quantifying the direct and significant indirect emissions from biofuels.”

Roughly 25 speakers offered slide-deck insight on a range of topics during the workshop. One particular session, “Overview of Modeling Frameworks of Crop-Based Biofuels,” offered a glimpse of what Kakesh and the ethanol industry believes is the latest science. Although multiple models exist, and can model the GHG emissions associated with crop-based biofuels, there is one that is the most accurate, Kakesh says.

Michael Wang, senior scientist and the director of the Systems Assessment Center at Argonne National Laboratory, provided an update on the GREET model (Greenhouse Gasses, Regulated Emissions and Energy Use In Technologies).

The GREET model is a one-of-a-kind analytical tool that simulates the energy use and emissions outputs of various vehicle and fuel combinations. It was started in 1995, but updated and expanded every year since by the DOE’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy.

During his presentation on GREET, Wang provided information that directly shows the impact corn-based ethanol can have on GHG emissions. Corn ethanol carbon intensity (CI) scores have decreased by 23 percent over the last 15 years. In technical terms: 14gCO2e/MJ. In 2019 alone, corn ethanol CI shows a 44 percent reduction compared to fossil fuel baseline (including land use change). Since 2005, corn farming also shows a GHG reduction of 15 percent.

Other models showing the lifecycle analysis were described during the workshop. There was a varying level of consensus on which specific LCA numbers related to biofuels or corn-based ethanol should be applied by the EPA when it decides how much biofuel should be required for the next RFS. Growth offered clarity to that point. “As several workshop presenters noted, it will not be possible to resolve every uncertainty related to biofuels LCAs in the time remaining before EPA must promulgate upcoming major rulemakings,” the organization wrote in its comments to the workshop.

To aid the EPA in its quest for the best science, Growth offered a study from EH&E, a multi-disciplinary team of environmental health scientists and engineers with expertise in measurements, models, data science, LCA and public health. The study, “Carbon Intensity of Corn Ethanol in the United States: State of the Science,” provided a meta-analysis of available LCA methodologies. The study gave a central estimate LCA for corn starch ethanol of 51gCO2e/MJ, or 46 percent below the 2005 petroleum baseline. Numbers that clearly show the positive impact of ethanol in any discussion on climate goals and overall CI reduction.

What Could Happen

Kakesh believes the EPA will set volume requirements for the next two years. The current administration’s goal of getting to net zero carbon by 2050 is not possible without biofuels, he adds. The experience of the EPA to set 2020 to 2022 RVOs will help in their efforts to set 2023 and beyond. And work on looking at LCA models and other issues will also help, Kakesh says of those March workshop presentations. After the November numbers are provided, the proposed volume obligations will be reviewed until June 2023, at which time, the EPA will have to finalize RVOs.

There are new biofuels related proposals floating through Washington, but until they evolve, the RFS remains the main political driver of direct biofuels production in the U.S. The RFS is, in fact, at a pivotal point, Kakesh says. The work of getting the EPA and others to set decision dates and hold workshops on modeling and GHG reduction scores is a major accomplishment for Growth and others.

The work to maintain and heighten the impact of the RFS on the potential for continued—and possibly increased—ethanol production, may not have reset anything quite yet, but the work to date has set the stage for a new era of RFS administration that takes fuller advantage of the benefits of ethanol.

Author: Luke Geiver

Contact: editor@bbiinternational.com

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Related Stories

CoBank’s latest quarterly research report, released July 10, highlights current uncertainty around the implementation of three biofuel policies, RFS RVOs, small refinery exemptions (SREs) and the 45Z clean fuels production tax credit.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration maintained its forecast for 2025 and 2026 biodiesel, renewable diesel and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) production in its latest Short-Term Energy Outlook, released July 8.

XCF Global Inc. on July 10 shared its strategic plan to invest close to $1 billion in developing a network of SAF production facilities, expanding its U.S. footprint, and advancing its international growth strategy.

U.S. fuel ethanol capacity fell slightly in April, while biodiesel and renewable diesel capacity held steady, according to data released by the U.S. EIA on June 30. Feedstock consumption was down when compared to the previous month.

XCF Global Inc. on July 8 provided a production update on its flagship New Rise Reno facility, underscoring that the plant has successfully produced SAF, renewable diesel, and renewable naphtha during its initial ramp-up.

Upcoming Events